Sustainable aviation fuel plans under fire over crop emissions

Environmental group and aviation industry disagree on how to assess the full climate impact of fuel made from corn and soybeans. The post Sustainable aviation fuel plans under fire over crop emissions appeared first on Trellis.

Key takeaways

- World Resources Institute urges U.S. policymakers and businesses to exclude corn and soybean fuels from plans to decarbonize aviation.

- Industry places both sources at the heart of expansion of sustainable aviation fuel use.

- State and federal regulators will likely be the key arbiters that shape company decisions.

For business flights that can’t be avoided, there’s only one near-term mitigation option: Sustainable aviation fuel (SAF), a lower-carbon alternative to fossil jet fuel.

Scaling SAF is the focus of the global strategy to decarbonize aviation, but researchers at the World Resources Institute (WRI) are urging a rethink of how the U.S. plans to do so. In a new report, the WRI team argues that when a more holistic approach is used to assess SAF production, two crops that are essential to scaling supply — corn and soy — are found to create more emissions than conventional fossil fuels.

The crops “are not a viable strategy for decarbonizing aviation,” said Audrey Denvir, a WRI research associate and an author of the report.

SAF advocates disputed the report’s conclusions, saying the researchers failed to distinguish between global averages and data on more sustainable biofuel crops grown in the U.S.

Scaling supply

Almost all SAF is currently produced from used cooking oil and other inedible biomass, and is broadly agreed to lead to real carbon savings when it displaces fossil jet fuel. But current production is tiny: The U.S. produces around 1 percent of the quantity needed to hit a government target of 3 billion gallons of domestic production by 2030, according to a 2024 Department of Energy report.

With limited additional waste oil available, the industry in the U.S. is relying on purpose-grown soy and corn to drive near-term growth. “Purpose-grown crops could constitute the majority of the supply within 6 to 10 years,” estimated Adam Klauber, who oversees sustainability and digital supply chains at World Energy, an SAF producer.

To qualify as SAF, fuels produced from these crops need to emit no more than 50 percent of the emissions from fossil jet fuel. Many in the industry say they do, but the\ researchers argue that assessment rests on faulty accounting.

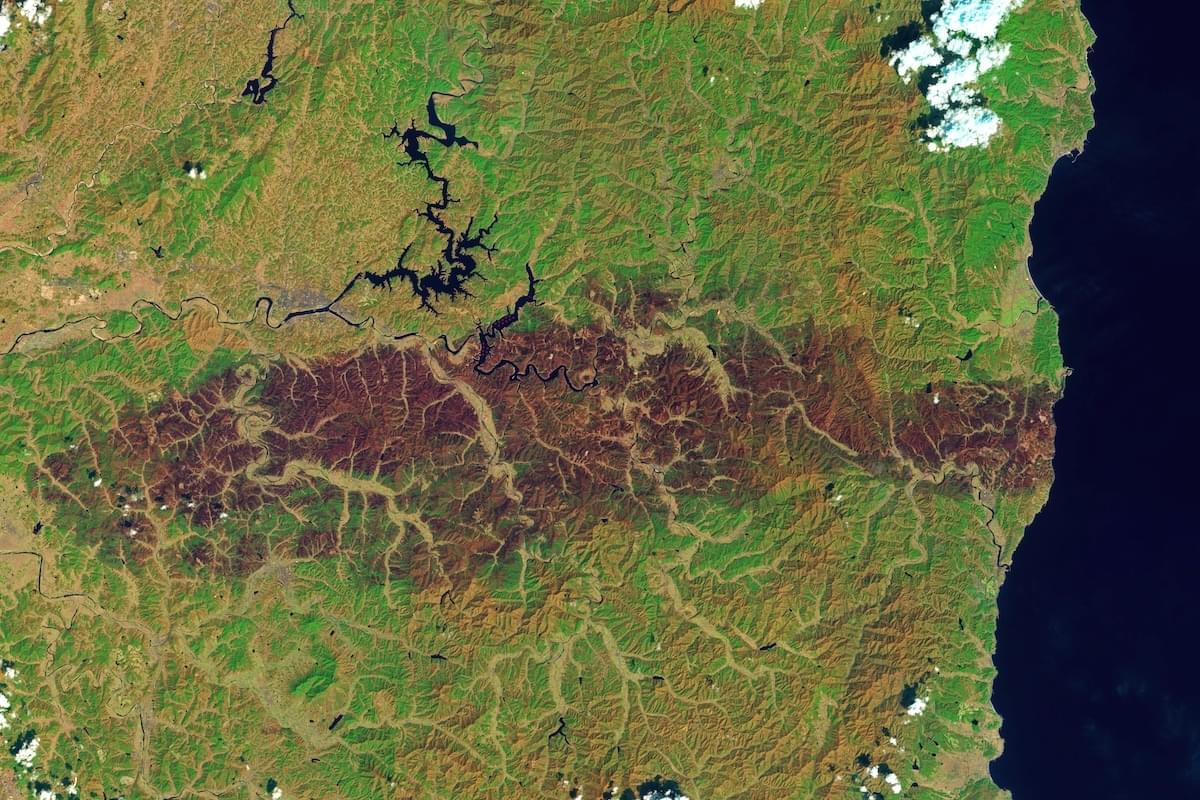

In a report released last week on how biomass can be used to decarbonize the U.S. economy, the researchers used a metric called “carbon opportunity cost” to calculate spillover impacts of fuel crops. As global demand for food grows, dedicating land for this purpose leads to forests and other native ecosystems being converted to agriculture, releasing additional emissions in the process. The fuels “actually increase emissions once you really account for all of the land use,” said Denvir. The European Union already excludes most biofuel crops from its SAF targets for similar reasons.

‘Context is everything’

Industry figures questioned key details of the analysis. Klauber argued that relying on global averages for the impacts of biofuel crops overlooks the higher performance of crops grown in the U.S. “Context is everything,” he said. In the case of soy production, for example, Klauber said the researchers used a carbon intensity figure that was several times higher than the one other academic and environmental organizations use.

Specific farming practices are also critical, he added. For example, biofuels can be grown either alongside and simultaneously with food crops, or during the shoulder season on either side of them. “That is broadly accepted as a sustainable practice, but it’s not yet at commercial scale,” said Klauber. “We’re working to increase that, because that really will be a way to increase the productivity of land without impacting food.”

A handful of organizations hold sway in determining which argument should govern growth of SAF in the U.S. The federal government, which oversees a clean energy tax credit known as 45Z that can apply to SAF, is unlikely to back more stringent environmental rules under the current administration. Regulators such as the California Air Resources Board also control certification schemes for SAF.

“The larger problem is on the demand side where business customers and buyers’ groups might exclude specific allowable feedstocks from contracts based on the perceived-negative public perception regarding soy or corn,” noted Klauber.

The post Sustainable aviation fuel plans under fire over crop emissions appeared first on Trellis.

![[Industry Direct] PHI Studio & Agog Are Seeking Immersive Artists for a Four Week Residency Program](https://roadtovrlive-5ea0.kxcdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/05/phi-immersive-residency-2-341x220.jpg?#)