Next-generation male contraceptives could rely on the perfect temperature

The protein CatSper works like a 'spermostat' to tell sperm when to get hyper. The post Next-generation male contraceptives could rely on the perfect temperature appeared first on Popular Science.

Sperm are somewhat like Goldilocks in their quest for everything to be just right. At least in mammals, the male sex cells are surprisingly picky about temperature and it can’t be too hot or too cold for them to do their thing. Sperm thrives in conditions only a few degrees cooler than normal body temperature. But they must endure warmer temperatures in the female reproductive tract in order to fulfill their destiny and fertilize an egg. But how?

Warmer temperatures appear to trigger a specific signal that activates the sperm into an important hyperactive state. Their motions switch from the relative smooth and steady movement used for navigation into the thrashing and twisting motions required to enter an egg. These findings in mice are detailed in a study recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

“It’s always exciting to uncover the molecular mechanism behind a well-known physiological phenomenon,” Polina V. Lishko, a study co-author and physiologist and cell biologist at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, tells Popular Science.”Everyone knew that male reproductive organs are maintained at a temperature lower than the core body temperature, but the reason why this is necessary wasn’t clearly understood—until now.”

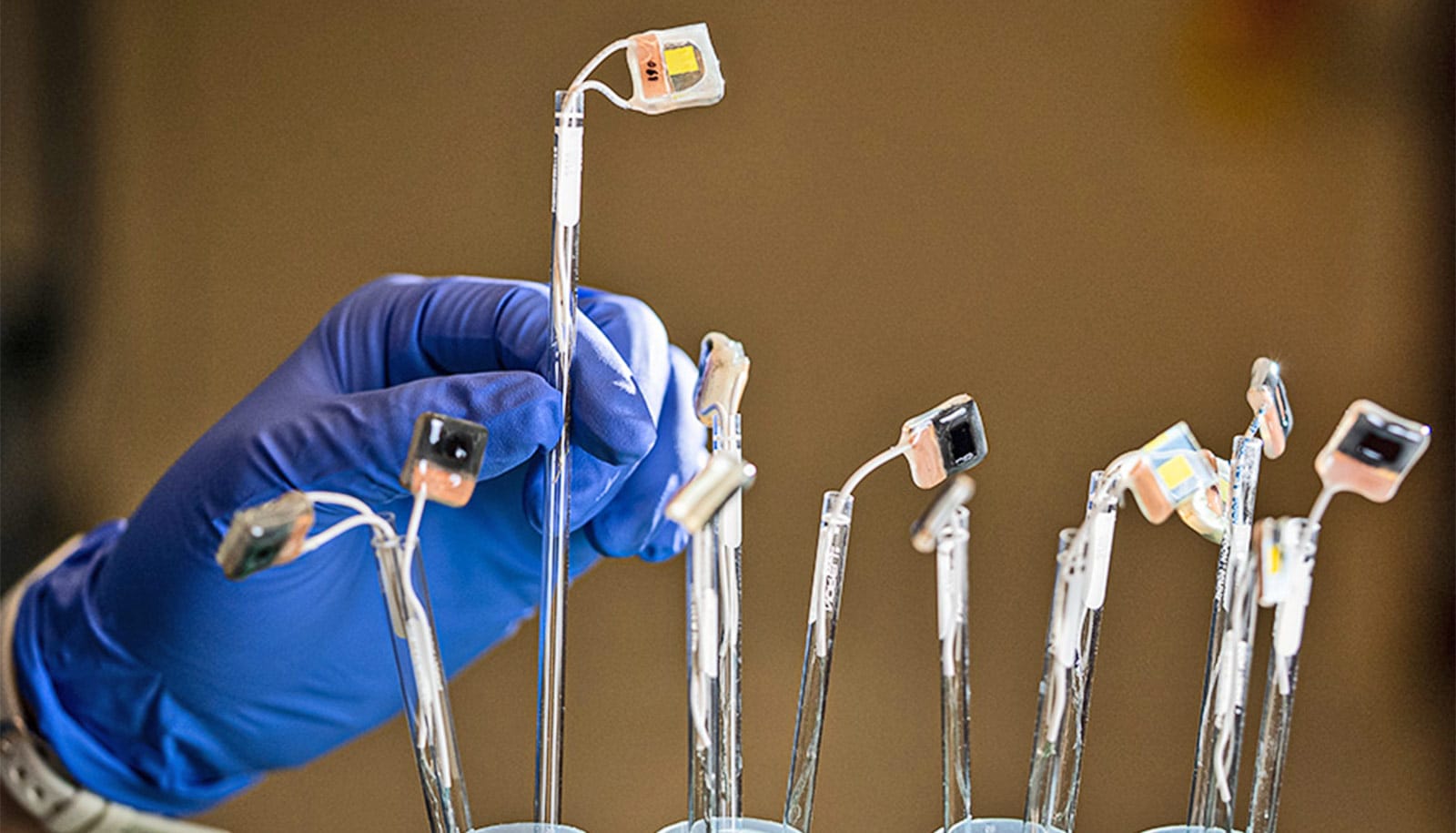

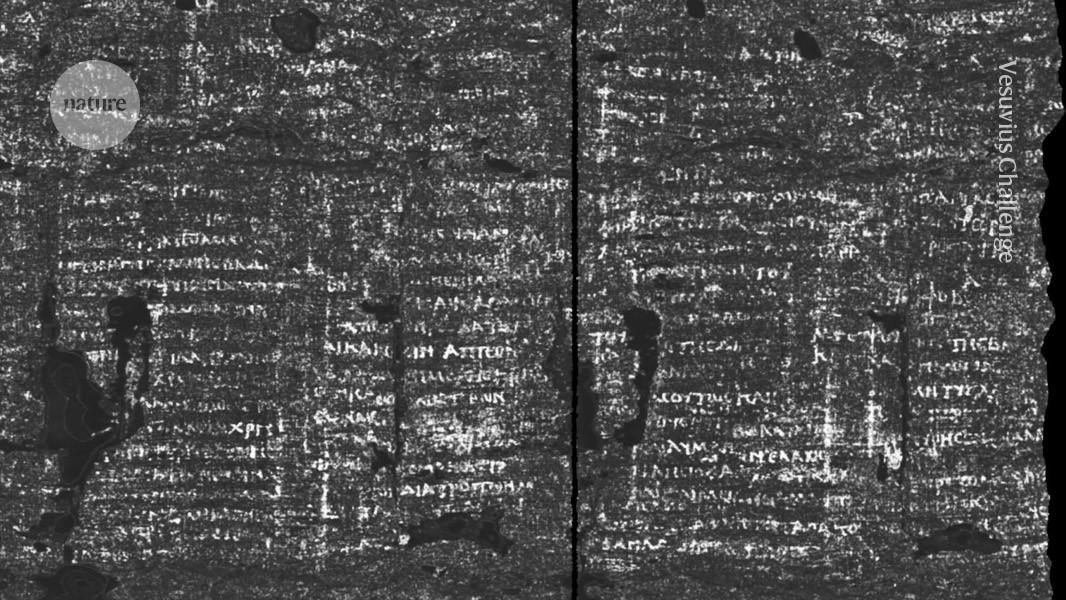

Credit: Polina LishkoCatSper the friendly protein

All mammals have a particular protein on the surface of sperm called CatSper. It controls the entry of the particles needed to power the hyperactive movements in the tail-like flagella that propels sperm forward to its target.

While temperature activation of CatSper was previously not known, scientists believed that the protein was activated by the pH level in the female reproductive channel. In primates, one female reproductive hormone called progesterone was also believed to activate CatSper. However, this theory didn’t fully hold up. According to Lishko, most mammalian sperm do not respond to progesterone. Another factor had to be pulling the strings behind the CatSper switch.

Temperature seemed like a primary factor, since mammalian evolution has developed numerous ways to help keep the male reproductive organs at or below the optimal 93.2 degrees Fahrenheit. Dolphins lower the temperature of the blood headed for their internal testes by passing it through their dorsal fin first. Elephants use their ears to cool blood down in a similar way. Humans and most other mammals create and store sperm in testicles located outside of their body to keep them cool. Birds and other animals that lack these cooling adaptations for their male reproductive organs also do not have CatSper proteins on their sperm.

[ Related: These sterile mice have been modified to make rat sperm. ]

Working like a ‘spermostat’

In the new study, Lishko and her team used tiny micron-scaled tools and techniques originally made to study brain cells. They observed the pattern of electric charges that are distinctive to CatSper’s activation in individual mice sperm cells. There were clear spikes when the temperature surrounding the cell went above 100.4 degrees.

Once the CatSper was activated, the sperm’s behavior switched from those relatively smooth motions used to navigate into the hyperactive movements needed for fertilization. In some ways, CatSper works like a thermostat, or “spermostat.”

For Lishko, “to once again witness how elegantly nature designs its elements,” was surprising and exciting.

Future applications

A better understanding of temperature’s role in fertility may help to improve both male contraception and infertility treatments. Since the CatSper protein only appears in sperm, targeting it wouldn’t affect other bodily functions.

Some next steps include exploring “whether we can achieve contraception (or increase fertility) by targeting this temperature-unique feature of sperm calcium channel,” says Lishko. While there have been some attempts to make male contraceptives that deactivate this calcium channel, those methods have not been very effective. The knowledge gained from this discovery might point to new approaches for doing so.

With more research, it could be possible to activate the CatSper with temperature changes and turn that calcium channel on to drain the sperm of energy, “so that by the time the sperm cell is ready to do its job and enter the egg cell, it is powerless.”

The post Next-generation male contraceptives could rely on the perfect temperature appeared first on Popular Science.