Surviving global catastrophe is a matter of community, not commerce

New research highlights the necessity of local farming during times of crisis. The post Surviving global catastrophe is a matter of community, not commerce appeared first on Popular Science.

Good news… at least relatively speaking. In the event of a catastrophic event like a nuclear attack or solar storm, an average-sized city’s (surviving) population doesn’t necessarily require a huge amount of nearby farming space to sustain itself. While the findings detailed in a study published May 7 in the journal PLOS One may seem a small comfort, emergency preparedness research can offer urban planners and government authorities valuable information on how to plan contingencies for an absolute worst case scenario.

Assessing global catastrophic risks

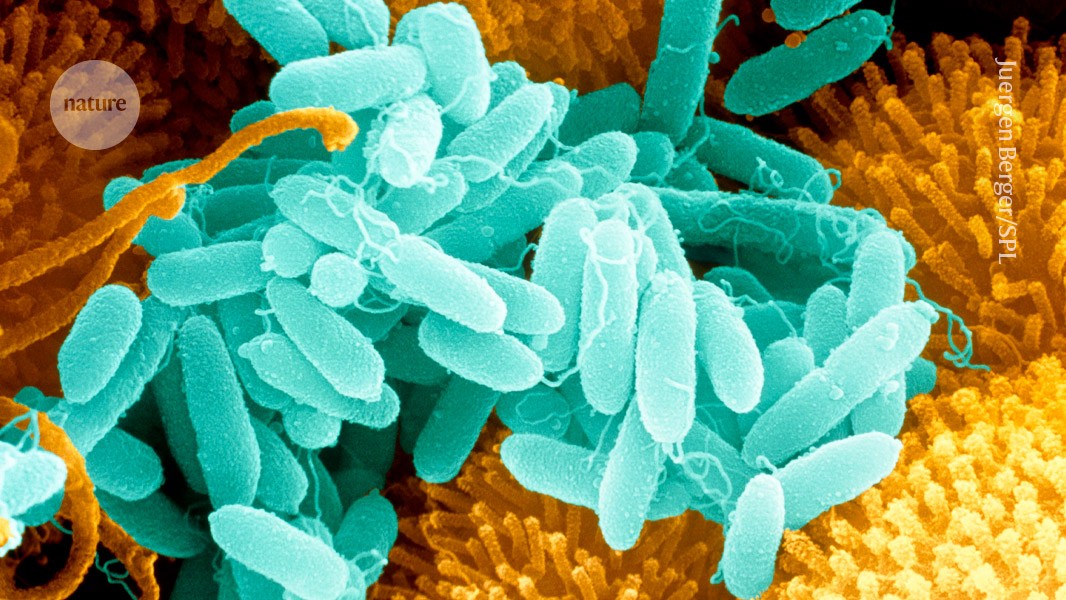

Certain nightmare events will be nearly impossible to endure as a species. For example, total nuclear war could easily render the planet inhabitable for the vast majority of life, including humans. The same can be said for an efficiently evolved supervirus or massive asteroid strike. While these are horrific to consider, more localized catastrophes like a dirty bomb’s radioactive fallout or a major solar storm frying a regional electrical grid are arguably more likely. But as scary as those still are, immediate survivors could endure and recover if they adopt strategic urban and near-urban agricultural practices.

“Abrupt global catastrophic risks (GCRs) are not improbable and could massively disrupt global trade leading to shortages of critical commodities, such as liquid fuels, upon which industrial food processing, processing, and distribution depends,” the authors wrote in the study.

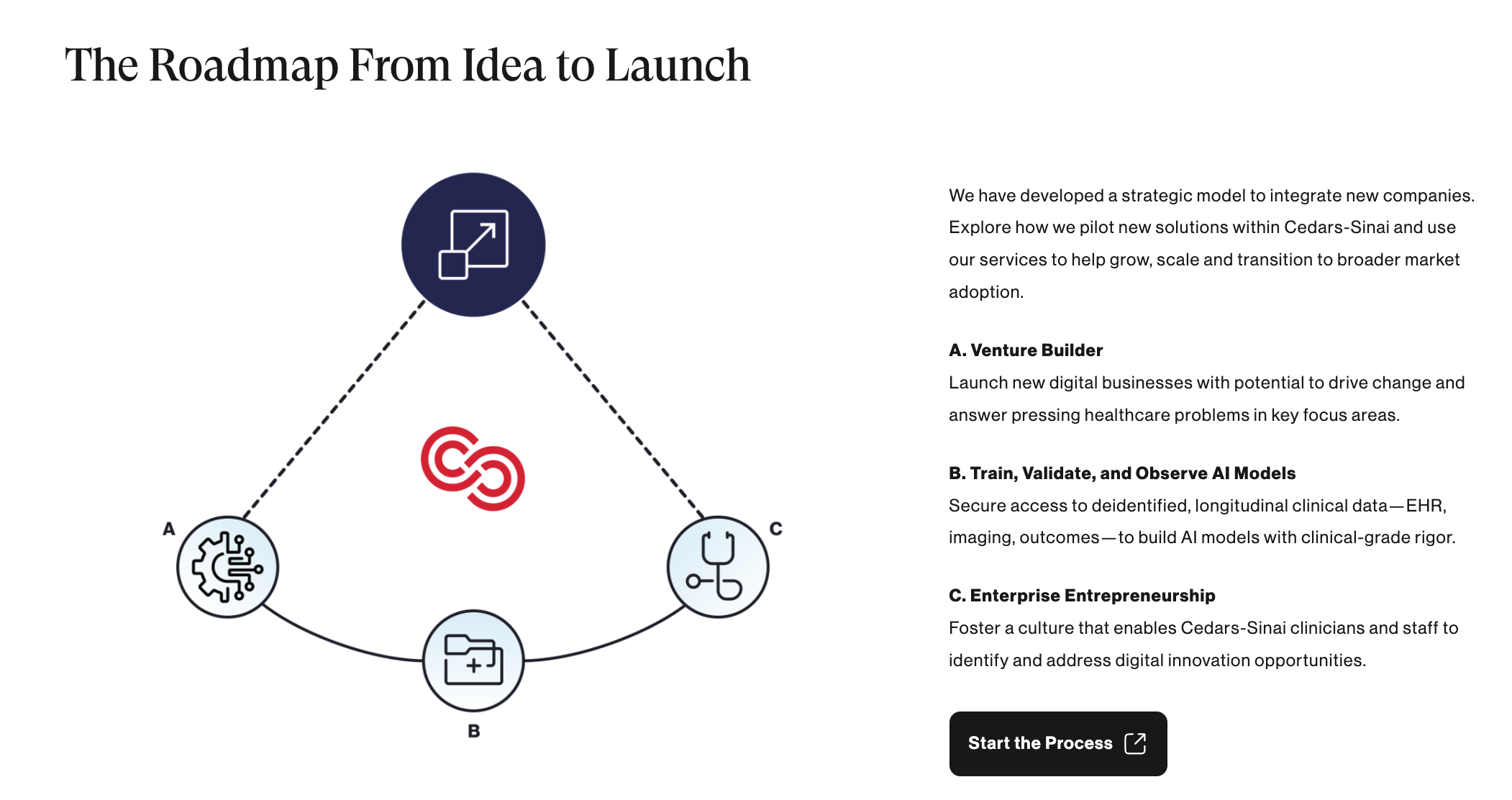

Previous work frequently examined urban agriculture techniques such as community, home, and rooftop gardens for resiliency planning. However, catastrophic risk consultant Matt Boyd argues that people need to broaden their scope if they hope to weather any potential dystopian lean times.

“During a global catastrophe that disrupts trade, fuel imports could cease, severely impacting the industrial food production and transportation systems that keep our supermarket shelves filled,” Boyd said in the study’s accompanying statement. “To survive, populations will need to dramatically localize food production in and around our cities. This research explores how we might do that.”

Peas, potatoes, sugar beets, and spinach

Boyd and co-author Nick Wilson at the University of Otago chose the New Zealand city of Palmerston North as their study’s post-apocalyptic scenario backdrop. Located on the North Island near the Manawatū River, Palmerston (Palmy, colloquially) is representative of many cities around the world, with a largely temperate climate and a population of around 91,000 residents. After analyzing Google Earth maps of the area to tally Palmy’s residential lots and open city spaces that could be used for crops, they concluded that even at optimal yields, the city would likely only provide about 20 percent of the food needed to survive.

But that’s not necessarily cause for despair. If the community dedicated at least 4.4 square miles of surrounding land to additional agricultural projects, that would close the gap for adequate food stores. What’s more, only about 0.4 square miles of extra land would be needed for the biofuel required to power agricultural machinery.

The team even offered a few helpful crop suggestions depending on your scenario: a “normal climate,” as well as “potential nuclear winter conditions.” Under current normal climatic patterns, urban gardens should concentrate on peas given their protein and calorie contents versus land requirements, while potatoes are the best bet for surrounding farmland. In the nuclear winter scenario, cities would need to focus on sugar beets and spinach, while near-urban plots handle wheat and carrots.

Societal-level cooperation

Boyd and Wilson have written extensively about how island communities and nations could serve as refuges during global catastrophes—an idea that many of the world’s wealthiest people support. Peter Thiel, the billionaire co-founder of PayPal and Palantir, spent years attempting to build an idyllic bunker in New Zealand, while Mark Zuckerberg owns a fortified “top-secret compound” in Hawai’i. LinkedIn co-founder and California Forever backer Reid Hoffman has proposed similar real estate ventures, while Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos has literally floated similar possibilities by investing in artificial island “seasteading” endeavors.

Many of these men cite a philosophy known as effective altruism (EA) as part of their reasoning. At its core, EA advocates that risk assessments and largescale societal planning is needed to ensure humanity survives in the extreme longterm, hopefully with the end goal of becoming an interstellar spacefaring civilization. Such a bird’s eye view of existence, however, can lead to extremely problematic lines of thought that are heartless at best, and actively eugenicist at worst. While he criticizes the movement’s recent hyperfixation on artificial intelligence, Boyd says he supports its general principles.

“The general philosophy of finding ways to do good most effectively and cost-effectively is admirable and I encourage it,” Boyd tells Popular Science. “… [But] the variables going into these calculations are so uncertain (uncertainty of orders of magnitude in some cases) that we shouldn’t lose sight of all possibilities.”

Instead of AI, Boyd believes society needs to focus on future “inevitable” pandemics and potential nuclear armageddon.

“We still lack preparation,” he says.

Regardless, Boyd doesn’t sound particularly concerned with billionaires potentially leveraging his work as evidence to pack up and flee to their newly constructed New Zealand safehouses.

“I think the concept of island refuges has been around for a while… and so it is a natural inclination for those with resources to want to establish some kind of safe haven on temperate islands,” conceded Boyd. “However, as further research of ours has shown, islands are also highly vulnerable (especially to trade and supply collapses), so [they will] need significant investment in resilience planning and infrastructure at a community/society level to actually thrive as a technological society.”

Boyd says he hopes more people begin considering the possibility of a global catastrophe, while keeping in mind that better resilience often only requires simple, low-tech options. These can take the form of community farm projects, as well as community members petitioning local leaders to focus on land use and zoning policies that support agriculture.

“I’m skeptical that some ‘billionaire bunkers’ will be particularly useful post catastrophe if civilization actually needs a reboot,” says Boyd. “Society-level cooperation and measures are probably needed.”

The post Surviving global catastrophe is a matter of community, not commerce appeared first on Popular Science.