Deadly ‘pharaoh’s curse fungus’ could be used to fight cancer

'Nature has given us this incredible pharmacy.’ The post Deadly ‘pharaoh’s curse fungus’ could be used to fight cancer appeared first on Popular Science.

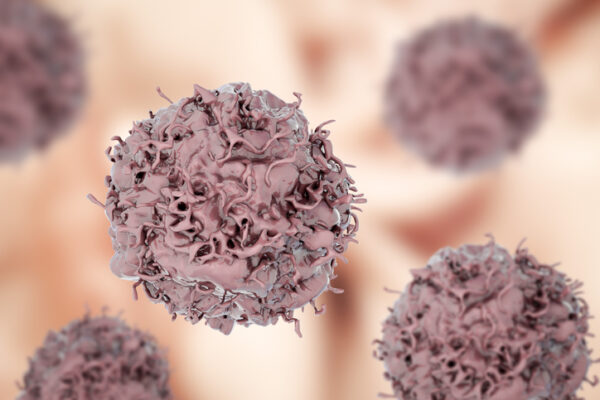

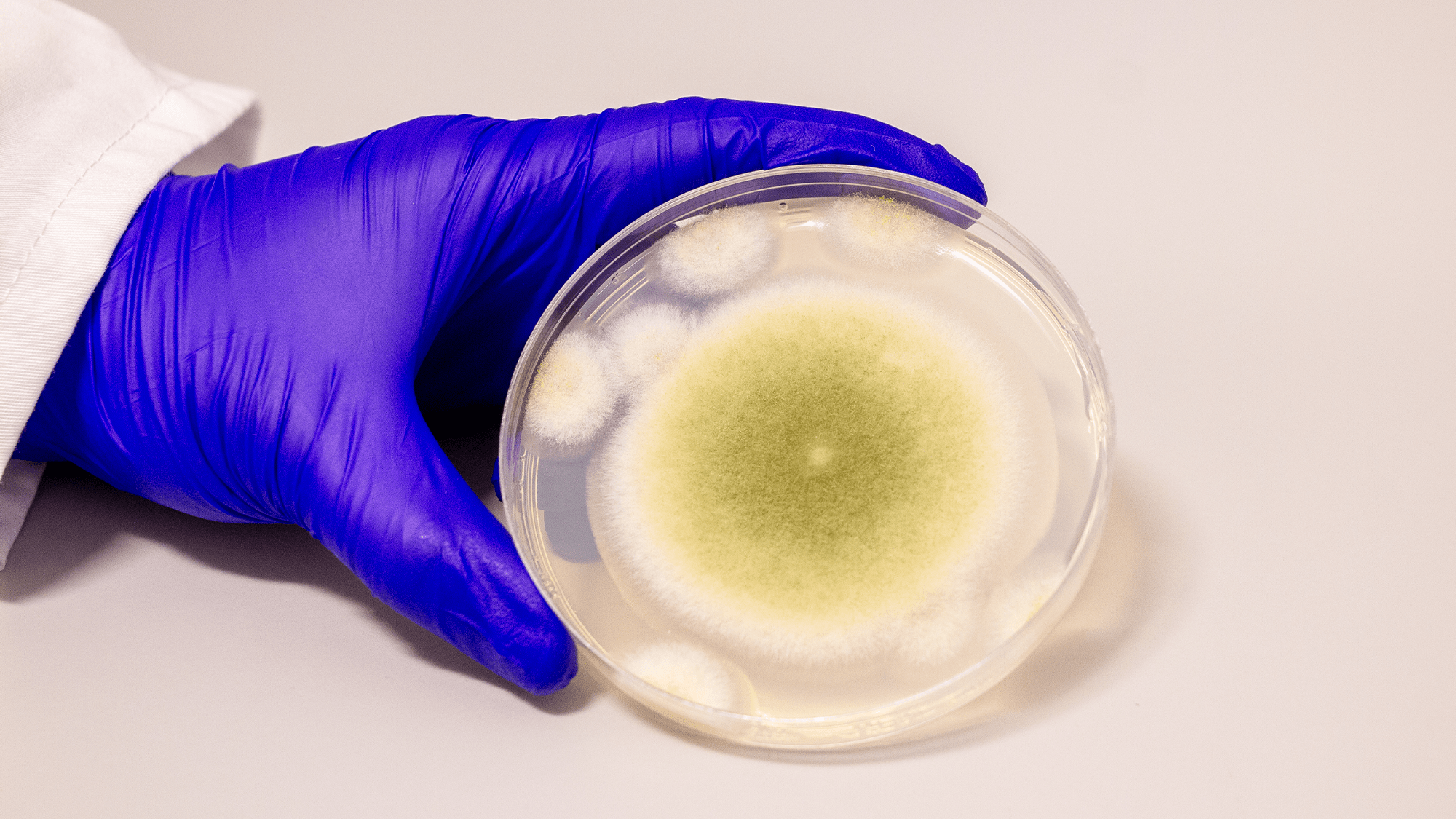

A deadly fungus linked to deaths in archeologists excavating ancient tombs has been turned into a new cancer-fighting compound. A team at the University of Pennsylvania modified some of the chemicals in the toxic crop fungus Aspergillus flavus, aka the “pharaohs’ curse” fungus, and created a new compound that kills leukemia cells. The findings are detailed in a study published June 23 in the journal Nature Chemical Biology and are an important step towards discovering new fungal medicines for cancer.

“Fungi gave us penicillin,” said Sherry Gao, a study co-author and UPenn chemical and biomolecular engineer, said in a statement. “These results show that many more medicines derived from natural products remain to be found.”

What is ‘pharoahs’ curse’ fungus?

Aspergillus flavus is one of the most frequently isolated mold species in both agriculture and medicine. It is commonly found in soil and can infect a broad range of important agricultural crops. The toxins in this fungus can lead to lung infections, especially in those with compromised immune systems. It is named for its dangerous yellow spores and has been considered a microbial villain for at least a century.

In the 1920s, after a team of archaeologists opened King Tutankhamun’s tomb near Luxor, Egypt, a series of untimely deaths occurred among the excavation team. Rumors swirled of some kind of pharoah’s curse. Doctors later theorized that fungal spores that had been dormant for thousands of years might have played a role in the deaths.

During excavations In the 1970s, a dozen scientists entered the tomb of Casimir IV in Poland. Within only a few weeks, 10 of the researchers died. Investigations later revealed the tomb contained the fungus A. flavus.

A deadly fungus for a deadly disease

The same deadly fungus is now being looked at as a potential cancer treatment. The therapy detailed in this new study is a class of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides, or RiPPs. The name “RiPP” refers to how the compound is produced. It starts in the ribosome–a small cellular structure that makes proteins–and is later modified by peptides or intervention in the lab. In this case, the RiPP is altered to enhance its cancer-killing properties.

“Purifying these chemicals is difficult,” said study co-author and UPenn doctoral fellow Qiuyue Nie.

While thousands of RiPPs have previously been identified in bacteria, only a handful have been discovered in fungi. One reason for fewer fungal RiPP finds is because past researchers likely misidentified fungal RiPPs as non-ribosomal peptides and did not quite understand how fungi created the molecules.

“The synthesis of these compounds is complicated,” adds Nie. “But that’s also what gives them this remarkable bioactivity.”

[ Related: College student discovers mysterious fungus that eluded LSD’s inventor. ]

Finding fungi

To find more fungal RiPPs, the team first scanned a dozen strains of different Aspergillus fungi. By comparing the chemicals produced by these strains with known RiPP building blocks, the team identified A. flavus as a promising candidate for additional study.

The genetic analysis pointed to a particular protein in A. flavus as a source of fungal RiPPs. When the team turned off the genes that create that protein, the chemical markers that indicated the presence of these RiPPs also vanished. Combining both metabolic and genetic information pinpointed the source of the useful fungal RiPPs in A. flavus and could be used to find other fungal RiPPs in the future.

The team then purified four different RiPPs. They found that the molecules all shared a unique structure of interlocking rings. The researchers named these previously undescribed molecules after the fungus in which they were found: asperigimycins.

Even without genetic modifications, the asperigimycins demonstrated medical potential when mixed together with human cancer cells. Two out of the four variants had potent effects against leukemia cells.

The researchers added a fatty molecule called a lipid to another variant and found that it performed as well as cytarabine and daunorubicin, two FDA-approved drugs that have been used to treat leukemia for decades.

A gateway gene

Next, the team wanted to understand why the lipids enhanced asperigimycins’ potency. To do this, the researchers selectively turned genes on and off in the leukemia cells. One gene (SLC46A3), proved critical in allowing asperigimycins to enter leukemia cells in the right amount. That SLC46A3 gene helps materials exit lysosomes, or tiny sacs that collect foreign materials entering human cells.

“This gene acts like a gateway,” said Nie. “It doesn’t just help asperigimycins get into cells, it may also enable other ‘cyclic peptides’ to do the same.”

Those chemicals have medicinal properties just like asperigimycins. Nearly 24 cyclic peptides have received clinical approval since 2000 to treat diseases from cancer and lupus, but many of them need modification in order to enter cells in sufficient quantities.

“Knowing that lipids can affect how this gene transports chemicals into cells gives us another tool for drug development,” said Nie.

Further experimentation showed that asperigimycins likely disrupt the process of cell division.

“Cancer cells divide uncontrollably,” said Gao. “These compounds block the formation of microtubules, which are essential for cell division.”

The compounds had little to no effect on breast, liver, or lung cancer cells or on a range of bacteria and fungi. According to the team, this suggests that asperigimycins’ disruptive effects are specific to certain types of cells, which is a critical feature for any future medication.

Secrets of nature’s pharmacy

In addition to showing that asperigimycins do have some future medical potential, the team pinpointed similar clusters of genes in other fungi. This means even more fungal RiPPS could be out there.

“Even though only a few have been found, almost all of them have strong bioactivity,” says Nie. “This is an unexplored region with tremendous potential.”

The next step towards potentially becoming a therapeutic, asperigimycins need to be tested in animal models, with the hope of one day moving into regulated human clinical trials.

“Nature has given us this incredible pharmacy,” says Gao. “It’s up to us to uncover its secrets. As engineers, we’re excited to keep exploring, learning from nature and using that knowledge to design better solutions.”

The post Deadly ‘pharaoh’s curse fungus’ could be used to fight cancer appeared first on Popular Science.