The unrealized promise of circular diapers

From big brands to startups, efforts to create circular diapers are crawling forward — but landfills are full of unrealized promises. The post The unrealized promise of circular diapers appeared first on Trellis.

Disposable diapers epitomize the excesses of the industrial, linear economy. After one nasty, short life, diapers trap organic matter in layers of plastics and paper pulp for hundreds of years in a landfill.

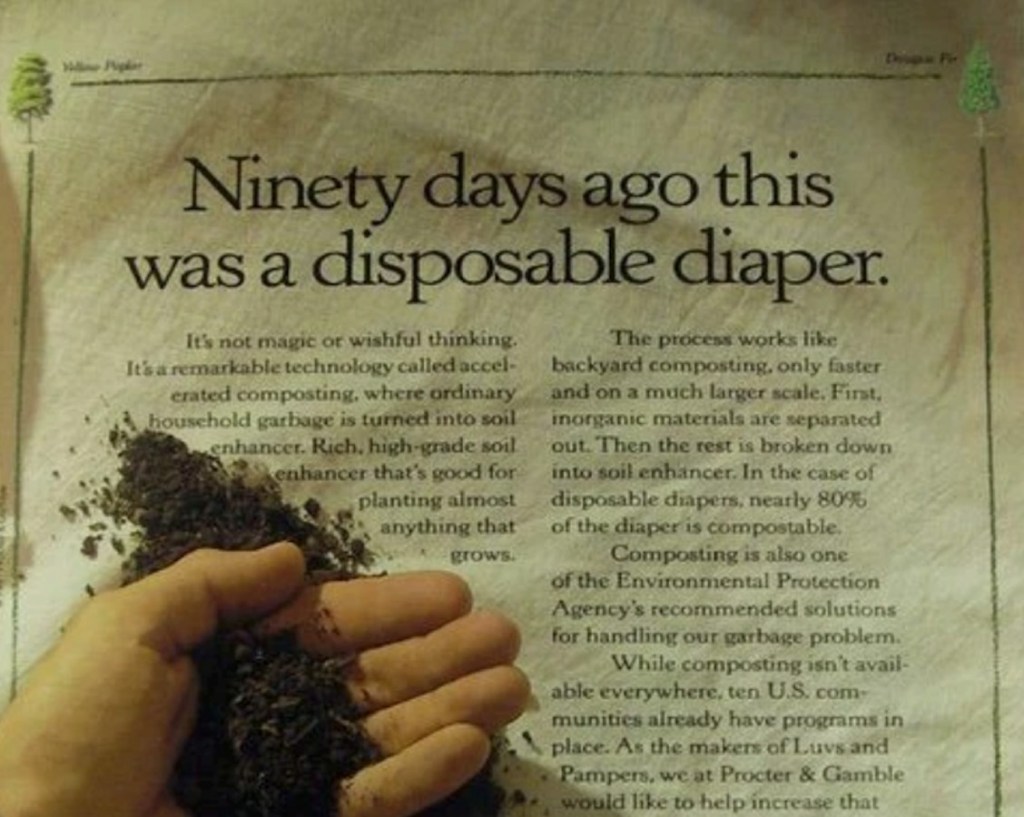

Efforts to change that have barely progressed in four decades, from Procter & Gamble’s groundless compostability claims in the early 1990s through the launch of countless “eco-friendly” personal care startups in recent years.

At least 90 percent of diapers in the developed world are single-use, bringing staggering levels of pollution. Each requires a cup of crude oil to produce. Every minute, 300,000 diapers go to the trash globally. And each American uses thousands of diapers in a lifetime, from the cradle to Depends.

In a market littered with companies pitching earth-friendly versions, Hiro Technologies became the latest in April, offering “mycodigestible” diapers that self-destruct with help from a hungry fungus packet.

“Our goal is to have diapers be circular, whether that is compostable, recycled or a combination thereof — or something new,” said Bart Jansen, lead product developer in sustainability at Ontex Global, a Belgian diaper maker with more than $2 billion in revenue and 5,500 employees. “We need to stop being in this linear model: We make products, you use them, you take them, you dispose of them, and they’re gone. There needs to be an alternative for that.”

Room for improvement

The botched 1991 attempt by the world’s biggest diaper maker, P&G, became a greenwashing case study that informed the Federal Trade Commission’s early “green guides” for marketers. Ten state attorneys general sued over an ad for Pampers and Luvs that showed a hand spilling over with black soil, declaring, “Ninety days ago this was a disposable diaper.”

P&G settled for only $50,000. Just a year earlier, it had announced a $20 million fund to engineer compostable diapers. In 1989, it had explored downcycling diapers into garbage bags and insulation for buildings.

Momentum to break the poop-and-toss cycle petered out for decades, at least publicly. But since 2017, P&G has backed an industrial diaper recycling plant in a joint venture in Italy that processes roughly 10,000 metric tons of waste each year. The facility separates the materials, recycling plastic to make bottle tops and cellulose for furniture.

Alas, 10,000 metric tons is less than 1 percent of the weight of P&G’s Pampers brand of diapers sold each year.

And Huggies parent Kimberly-Clark, the No. 2 diaper maker, has not done much to scale circular diapers, either, beyond small projects like Nappy Loop composting in Australia.

Meanwhile, the disposable diaper space is set to grow from $79 billion in 2025 to $115 billion by 2030, according to Grand View Research. And the market for biodegradable diapers, in particular, is expected to double from $4 billion last year to $8 billion in 2033, according to IMARC Group. The definition of “biodegradable” is loose here, however, describing natural fibers such as bamboo and cotton. In theory, such materials degrade in nature. How they behave when composted is another matter — and ripe for greenwashing.

Numerous startups have attempted to fill the innovation gap left by P&G and Kimberly-Clark, which corner three quarters of the baby diaper market. Here’s a tour of some of the most promising:

Fungus forward: Hiro Technologies

Why can’t diapers mimic the pattern in nature, whereby decomposers eat waste and release nutrients? That’s what serial entrepreneur Miki Agrawal is pursuing with diaper startup Hiro Technologies. “We’re the first company to actually take plastic-eating fungi out of a lab and into a product,” she said.

Her team in Austin, Texas, grows fungi to create a shelf-stable, matchbook-size packet that “eats” used diapers. Parents take a spent diaper, pop in the fungus square and toss it all into the trash. In test conditions, the fungus transforms the diaper into compost within a year, according to the company.

Its diapers feature 80 percent unbleached cotton and wood pulp, plus 20 percent polypropylene and polyethylene. The plastic is necessary for performance, according to Agrawal. However, she wants to replace it eventually with a bio-based polymer.

Hiro is angel-funded, including backers of Agrawal’s previous startups, the bidet brand Tushy and the period underpant maker Thinx (bought by Kimberly-Clark in 2023).

Hiro Technologies’ near-term goal is for 10,000 customers to subscribe to diaper deliveries for about $140 per month. It’s pursuing third-party validations for compostability, biodegradability and nontoxic materials.

Agrawal’s son, Hiro, inspired the idea for the company as a toddler. “One day, we’re outside looking at trees, and I was like, Breast milk is liquid gold; you can’t waste a drop,” she said. “And so baby poop must be fertilizer gold. But right now we’re wrapping up this potent fertilizer in plastic and just throwing it away in the trash, billions of pounds … and not harnessing it for good.”

Hiro diapers, however, are not designed to transform into commercial compost. Most likely, they end up in landfills.

Grounded in composting: Dyper, Terracycle

Most composting facilities refuse dirty diapers, no matter what their material.

But some startups are nonetheless pursuing a back-to-nature strategy by marketing their diapers as compostable or biodegradable. Dyper of Scottsdale, Arizona, for example, ships a monthly $100 box of plant-based diapers directly to consumers. For another $65, customers in select regions can leave a plant-based plastic bag packed with dirty diapers on their doorstep for weekly pickups.

The Trenton, New Jersey, company Terracycle provides industrial composting through its Redyper service to create compost in several months. The composting sites, whose locations remain undisclosed by both companies, would require specific permits to handle human waste, which most composting facilities reject as a biohazard. Compost involving transformed human waste often winds up in landscaping.

gDiapers for the Greater Good Project

The regulatory hurdles of diaper composting in the developed world recently led longtime wife-and-husband diaper entrepreneurs to pivot. For two decades, Australians Kim and Jason Graham-Nye sold gDiapers. These colorful cotton-spandex diaper bloomers held maxipad-like inserts made of nylon, wood pulp and an absorbent polymer, designed for composting.

Supply chain troubles during the COVID-19 pandemic led gDiapers to fold. Now the couple is bringing a version of gDiapers to Pacific Island nations, where nappies make up 27 percent of household waste, to prove out regional circular economies. They’re bringing the Greater Good Diaper Project to Tuvalu this year after launching in Samoa in 2024 with support from that government.

The system eliminates 1,500 pounds of diaper waste and can produce 400 pounds of compost per week, according to Graham-Nye.

The nonprofit employs local women to deliver and collect diapers several times a week. They bring wet nappies to a “no tech composting facility” of timber boxes and community waste. An inoculant involving local coconuts reduces odor. In six to eight weeks, compost emerges.

“In a global south context, they’re very comfortable applying it to crops,” said Graham-Nye. “In the global north, there’s lots of nervousness. It’s not a scientific thing. It’s an ick factor thing.”

All of the above: Ontex Global

In northern Europe, diaper maker Ontex Global has partnered with other organizations on reuse, composting and recycling pilots. A diaper recycling effort in Flanders led to a spinoff, Woosh, that delivers to and picks up from daycare centers.

In 2021, Ontex Global announced a goal to compost 500 million diapers by 2030 with Parisian nonprofit partner Les Alchimistes. Although that target may be tough to achieve, the project helped to establish a legal framework in France to allow composting diapers under regulations related to the industrial sludge management, according to Jansen of Ontex.

That said, restrictions on waste management in other E.U. nations limit the ability to experiment.

Other difficulties include creating high-performance, bio-based and compostable products. Diapers built to be torn apart and recycled later may be easier to design, according to Jansen. Creating a long-lasting, super-absorbent polymer for the core of the diaper is a steep engineering challenge. So is competing on price with conventional diapers.

“We’re not there yet but technology is advancing,” said Jansen.

Tempering claims

For now, however, the risks of making unproven claims about nature-friendly diapers haven’t changed much since P&G’s infamous 1991 ad.

Only reusable cloth diapers, holding steady at about 5 percent of the overall market, offer meaningful circularity.

And while it’s true that bamboo, corn, cotton, hemp and sugarcane materials have since entered the mix, many marketing labels overpromise, according to Neil Edgar, executive director of the California Compost Collection. In other words, don’t trust or perpetuate “compostable,” “biodegradable,” “eco-conscious,” “eco-friendly,” “pure” and “natural” language.

“They were starting up some of those companies back when I was raising my daughter in the Bay Area,” said Edgar. “My daughter’s 32 now. It’s mostly mythology. Those dreams are unicorns.”

The post The unrealized promise of circular diapers appeared first on Trellis.