Circadian ‘clocks’ show humans are seasonal creatures

"The study shows that our biologically hardwired seasonal timing affects how we adjust to changes in our daily schedules."

New research shows that the circadian “clocks” of humans are tracking the changing amount of daylight across seasons.

It’s tempting to think that, with our fancy electric lights and indoor bedrooms, humanity has evolved beyond the natural influence of sunlight when it comes to our sleep routines.

“Humans really are seasonal, even though we might not want to admit that in our modern context,” says study author Ruby Kim, a University of Michigan postdoctoral assistant professor of mathematics.

“Day length, the amount of sunlight we get, it really influences our physiology. The study shows that our biologically hardwired seasonal timing affects how we adjust to changes in our daily schedules.”

This finding could enable new ways to probe and understand seasonal affective disorder, a type of depression that’s connected to seasonal changes. It could also open new areas of inquiry in a range of other health issues that are connected to the alignment of our sleep schedules and circadian clocks.

For example, researchers—including the study’s senior author, Daniel Forger—have previously shown that our moods are strongly affected by how well our sleep schedules align with our circadian rhythms.

“This work shows a lot of promise for future findings,” Kim says of the new study published in the journal npj Digital Medicine.

“This may have deeper implications for mental health issues, like mood and anxiety, but also metabolic and cardiovascular conditions as well.”

The research also shows there is a genetic component of this seasonality in humans, which could help explain the vast differences in how strongly individuals are affected by changes in day length.

“For some people they might be able to adapt better, but for other people it could be a whole lot worse,” says Forger, professor of math and director of the Michigan Center for Applied and Interdisciplinary Mathematics.

Exploring this genetic component will help researchers and doctors understand where individuals fall on that spectrum, but getting to that point will take more time and effort. For now, this study is an early but important step that reframes how we conceive of human circadian rhythms.

Two boxes are side by side showing charts of the activity and circadian rhythms of two different participants in the Intern Health Study. Each chart is divided into horizontal lines indicating different days and, left to right, the chart shows what time of day it is according to the participant’s circadian clock. Black marks above each horizontal line indicate when a participant was active and taking steps, and the clusters fall into different spots along circadian time because of an intern’s shift work schedule.

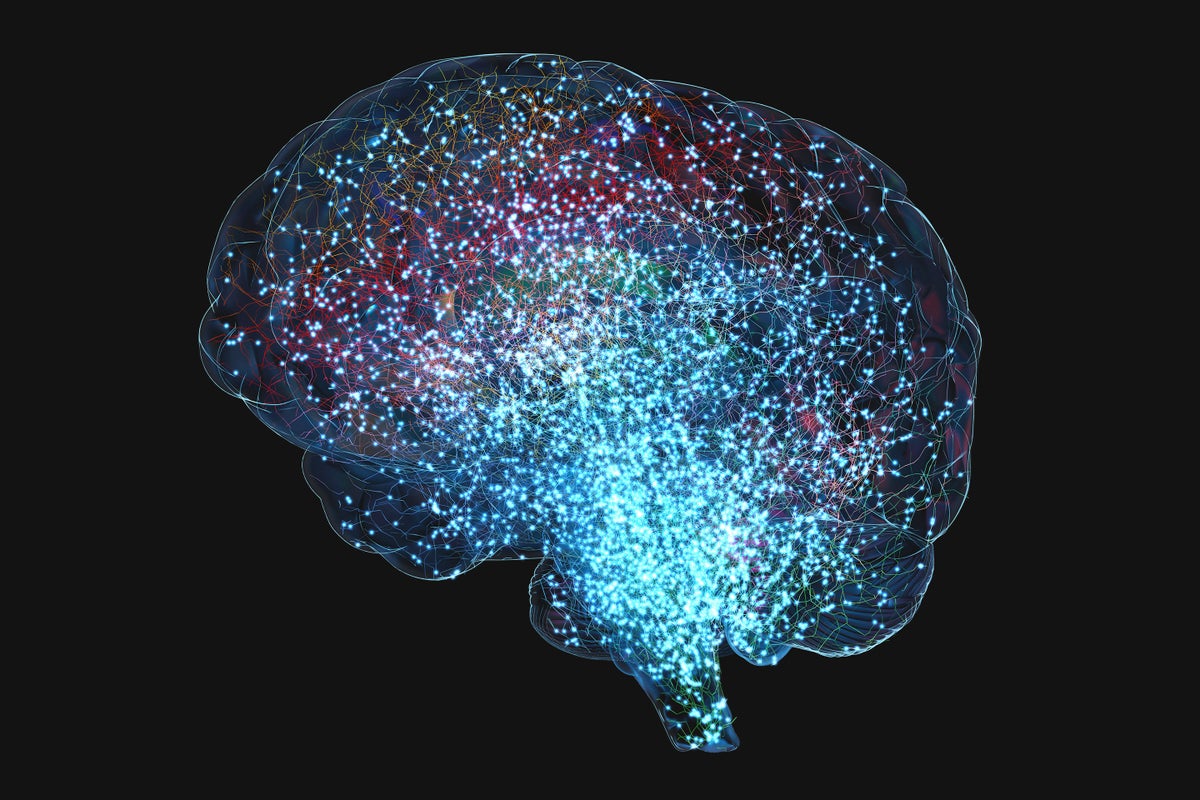

“A lot of people tend to think of their circadian rhythms as a single clock,” Forger says. “What we’re showing is that there’s not really one clock, but there are two. One is trying to track dawn and the other is trying to track dusk, and they’re talking to each other.”

Kim, Forger, and their colleagues revealed that people’s circadian rhythms were tuned into the seasonality of sunlight by studying sleep data from thousands of people using wearable health devices, like Fitbits. Participants were all medical residents completing a one-year internship who had enrolled in the Intern Health Study, funded by the National Institutes of Health.

Interns are shift workers whose schedules change frequently, meaning their sleep schedules do as well. Furthermore, these schedules are often at odds with the natural cycles of day and night.

The fact that circadian rhythms in this population exhibited a seasonal dependence is a compelling argument for just how hardwired this feature is in humans, which isn’t altogether surprising, the researchers say.

There’s a lot of evidence from studies of fruit flies and rodents that animals possess seasonal circadian clocks, Forger says, and other researchers have thought humans’ circadian clocks may behave similarly. Now, the new research has provided some of the strongest support for the idea yet in observing how that seasonality plays out in a large, real-world study.

“I think it actually makes a lot of sense. Brain physiology has been at work for millions of years trying to track dusk and dawn,” Forger says.

“Then industrialization comes along in the blink of evolution’s eye and, right now, we’re still racing to catch up.”

Participants in the Intern Health Study also provide a saliva sample for DNA testing, which enabled Kim and Forger’s team to include a genetic component of their study. Genetic studies led by other researchers have identified a specific gene that plays an important role in how other animals’ circadian clocks track seasonal changes.

Humans share this gene, which allowed the researchers to identify a small percentage of interns with slight variations in the genetic makeup of that gene. For that group of people, shift work was more disruptive to the alignment of their circadian clocks and sleep schedules over seasons.

Again, this raises many questions especially about health implications and the influence of shift work on different individuals. But these are questions the researchers plan to explore in the future.

Source: University of Michigan

The post Circadian ‘clocks’ show humans are seasonal creatures appeared first on Futurity.