City living is changing rodent skulls in Chicago

‘Museum collections allow you to time travel.’ The post City living is changing rodent skulls in Chicago appeared first on Popular Science.

Tiny rodents living in a major American city are unique examples of evolution playing out in real time.

Like geologic time itself, the process of evolution itself is generally a very slow process with teeny tiny changes passed down over several generations. All of these small changes eventually result in new adaptations and potentially new species over thousands or millions of years. However, in the face of dramatic shifts in the world around them from climate change to human encroachment, species sometimes must rapidly adapt or die.

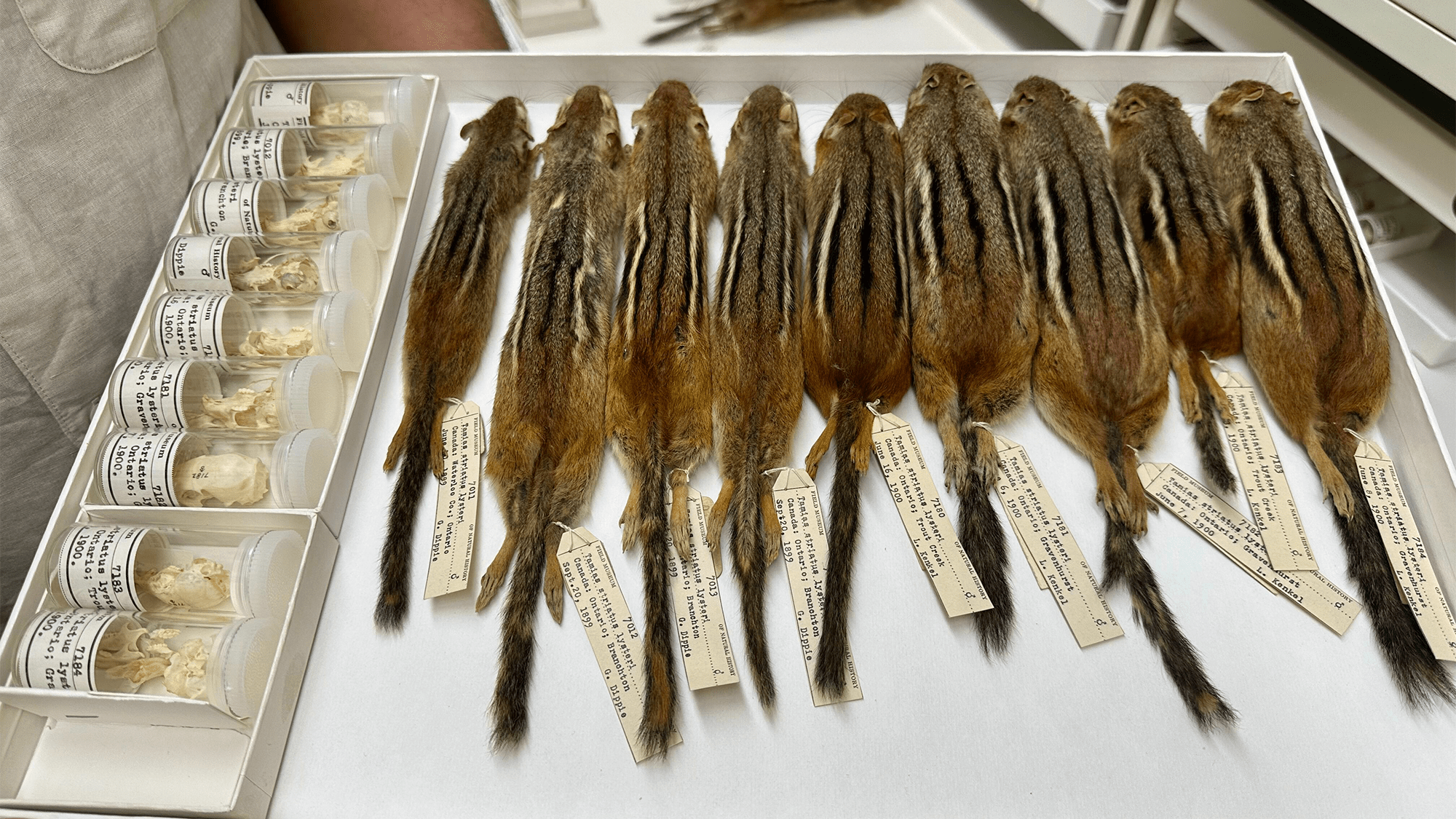

One of these rapid examples of evolution was hidden away in the drawers of Chicago’s Field Museum. While comparing the skulls of common chipmunks and voles found in the Chicagoland area collected over the past 125 years, a team found evidence that these rodents have been adapting to life in an increasingly urban environment. The findings are detailed in a study published June 26 in the journal Integrative and Comparative Biology.

“Museum collections allow you to time travel,” Stephanie Smith, a study co-author and mammalogist at the Field Museum, said in a statement. “Instead of being limited to studying specimens collected over the course of one project, or one person’s lifetime, natural history collections allow you to look at things over a more evolutionarily relevant time scale.”

The mammal collections at the museum include over 245,000 specimens from all over the world. Given its location in the Windy City, they have an especially good representation of the animals from Chicago, including raccoons, skunks, a one-in-a-million blue eyed cicada, opossums, robins, and much more. The collections also represent different moments in time throughout the past century.

“We’ve got things that are over 100 years old, and they’re in just as good of shape as things that were collected literally this year,” said Smith. “We thought, this is a great resource to exploit.”

In the new study, the team selected two rodents commonly found in Chicago: eastern chipmunks (Tamias striatus) and eastern meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus).

“We chose these two species because they have different biology, and we thought they might be responding differently to the stresses of urbanization,” added study co-author and Field Museum assistant curator of mammals Anderson Feijósa.

Chipmunks are members of the same family as squirrels. The small rodents spend most of their time aboveground, eating seeds, nuts, fruits, insects, and even frogs. Voles, on the other hand, are more closely related to hamsters. They prefer to spend their time in underground burrows and primarily eat plants.

[ Related: Squirrels gamble, too—but with their genes. ]

Field Museum Women in Science interns and study co-authors Alyssa Stringer and Luna Bian, measured the skulls of 132 chipmunks and 193 voles. Skulls contain important information about an animals’ sensory systems and diet, and they tend to be correlated with their overall body size.

“From the skulls, we can tell a little bit about how animals are changing in a lot of different, evolutionary relevant ways—how they’re dealing with their environment and how they’re taking in information,” said Smith.

Stringer and Bian measured different parts of the skulls, noting the overall skull length, the length of the rows of teeth, and other characteristics. They also created 3D scans of the skulls of 82 of the chipmunks and 54 of the voles. This part of the analysis is called geometric morphometrics, and it digitally stacked the skull scans on top of each other so scientists could compare the distances between different, specific points.

They found small–but significant–changes in the rodents’ skulls over the past 100 years. For the chipmunks, their skulls became larger over time, while the row of teeth along the sides of the mouths shrank. The bony bumps in the voles’ skulls that hold the inner ear became smaller over time. However, why the skulls were changing was not immediately clear.

To search for the reason behind these skull changes, the team pored over historical records on temperature and levels of urbanization around the Chicagoland area.

“We tried very hard to come up with a way to quantify the spread of urbanization,” says Feijó. “We took advantage of satellite images showing the amount of area covered by buildings, dating back to 1940.” The specimens collected before 1940 were from two different places: areas that were still wild 85 years ago (so it could safely be assumed that these spots were wild before that) and or from highly urbanized areas like downtown Chicago.

Changes in climate didn’t explain the alterations in the rodents’ skulls, but the degree of urbanization did. The differences in the ways that the skulls changed could be related to the different ways that they were affected by an increasingly urban habitat.

“Over the last century, chipmunks in Chicago have been getting bigger, but their teeth are getting smaller,” said Feijó. “We believe this is probably associated with the kind of food they’re eating. They’re probably eating more human-related food, which makes them bigger, but not necessarily healthier. Meanwhile, their teeth are smaller—we think it’s because they’re eating less hard food, like the nuts and seeds they would normally eat.”

By contrast, the voles had smaller auditory bullae–bone structures associated with hearing.

“We think this may relate to the city being loud—having these bones be smaller might help dampen excess environmental noise,” said Smith.

While it’s clear that these rodents could evolve small changes over time to make it easier to live among humans, the team says that the overarching lesson is not that animals will just adapt to whatever humans can throw at them. Instead, the voles with smaller ear bones and chipmunks with smaller teeth prove just how profoundly human beings affect our environment and how much we can make the world harder for our fellow animals.

“These findings clearly show that interfering with the environment has a detectable effect on wildlife,” said Feijó.

“Change is probably happening under your nose, and you don’t see it happening unless you use resources like museum collections,” concluded Smith.

The post City living is changing rodent skulls in Chicago appeared first on Popular Science.