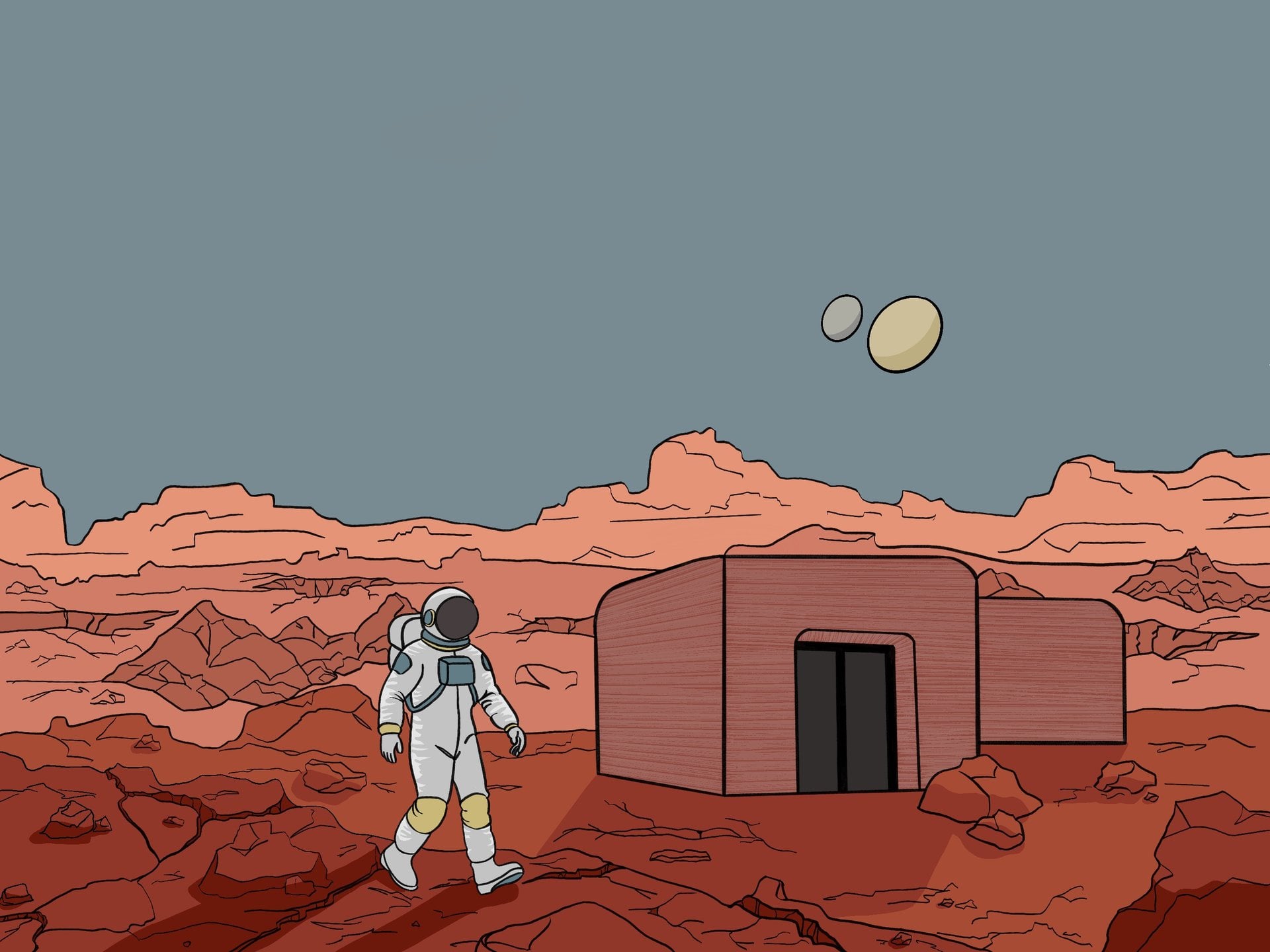

NASA Mars Orbiter Learns New Moves After Nearly 20 Years in Space

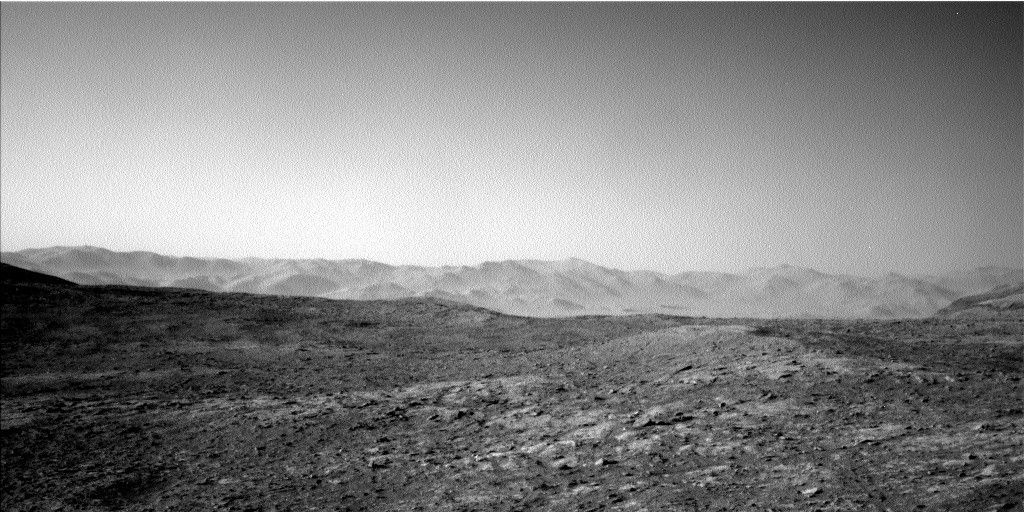

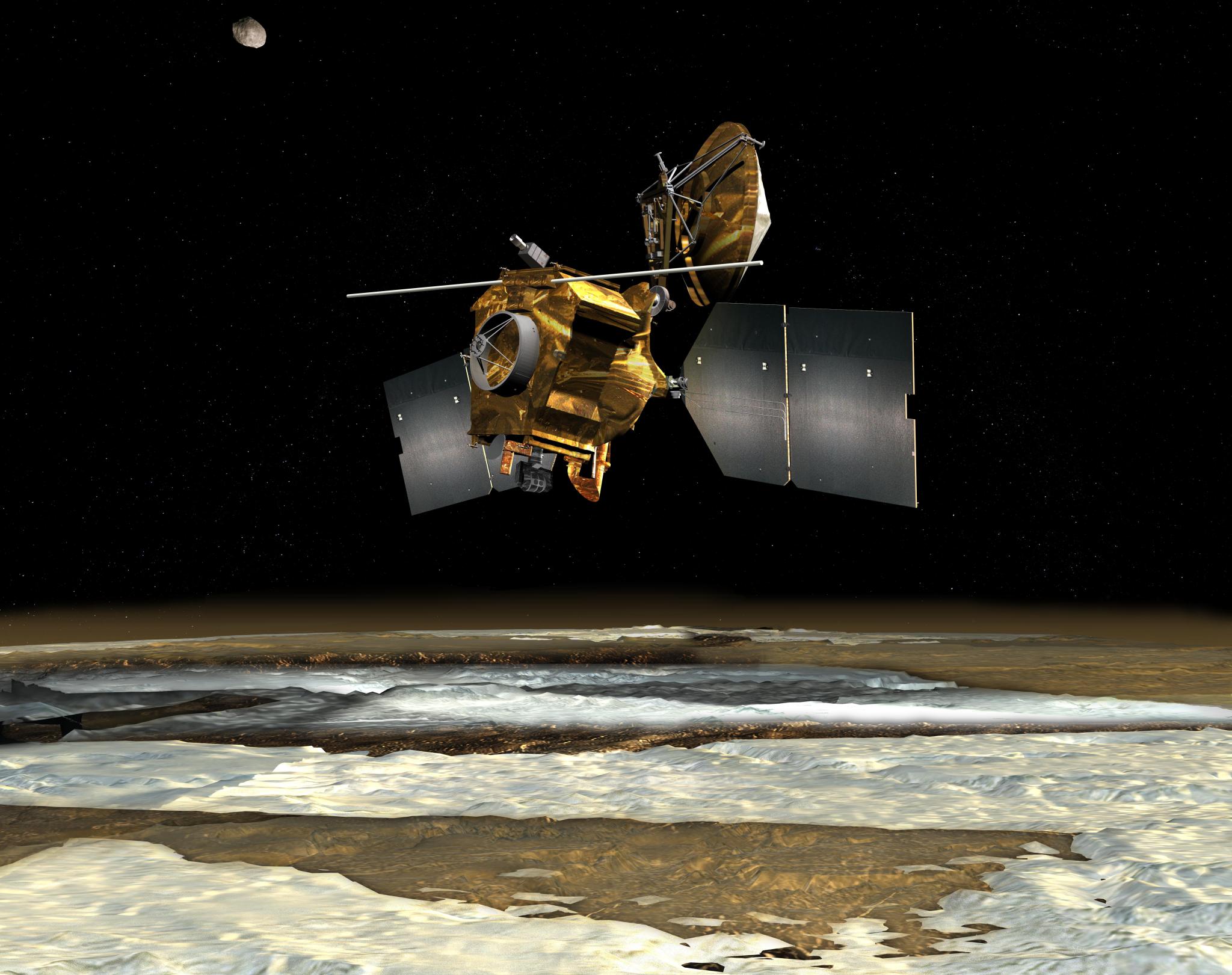

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is testing a series of large spacecraft rolls that will help it hunt for water. After nearly 20 years of operations, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is on a roll, performing a new maneuver to squeeze even more science out of the busy spacecraft as it circles the Red Planet. Engineers […]

6 min read

Preparations for Next Moonwalk Simulations Underway (and Underwater)

The Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is testing a series of large spacecraft rolls that will help it hunt for water.

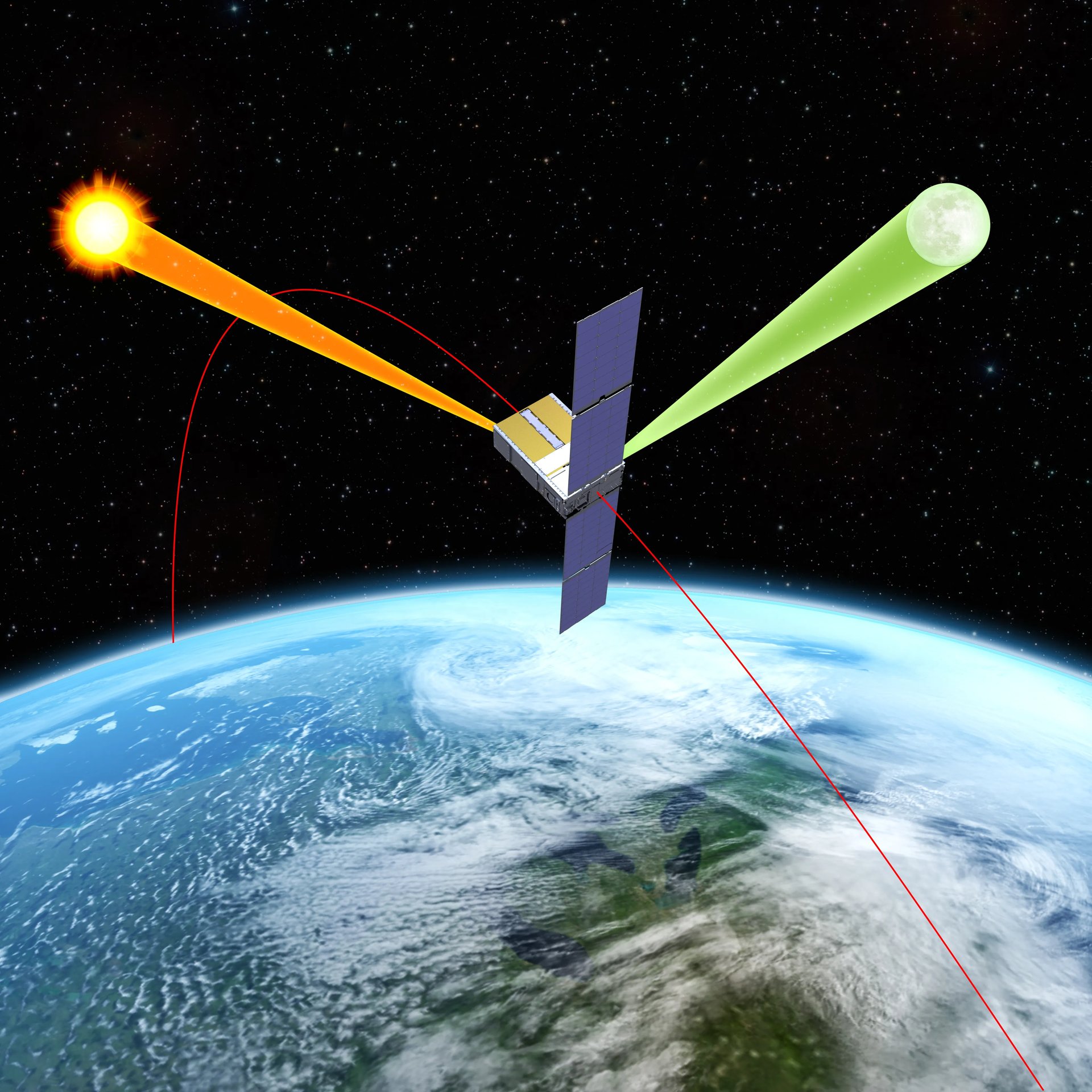

After nearly 20 years of operations, NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) is on a roll, performing a new maneuver to squeeze even more science out of the busy spacecraft as it circles the Red Planet. Engineers have essentially taught the probe to roll over so that it’s nearly upside down. Doing so enables MRO to look deeper underground as it searches for liquid and frozen water, among other things.

The new capability is detailed in a paper recently published in the Planetary Science Journal documenting three “very large rolls,” as the mission calls them, that were performed between 2023 and 2024.

“Not only can you teach an old spacecraft new tricks, you can open up entirely new regions of the subsurface to explore by doing so,” said one of the paper’s authors, Gareth Morgan of the Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona.

The orbiter was originally designed to roll up to 30 degrees in any direction so that it can point its instruments at surface targets, including potential landing sites, impact craters, and more.

“We’re unique in that the entire spacecraft and its software are designed to let us roll all the time,” said Reid Thomas, MRO’s project manager at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California.

The process for rolling isn’t simple. The spacecraft carries five operating science instruments that have different pointing requirements. To target a precise spot on the surface with one instrument, the orbiter has to roll a particular way, which means the other instruments may have a less-favorable view of Mars during the maneuver.

That’s why each regular roll is planned weeks in advance, with instrument teams negotiating who conducts science and when. Then, an algorithm checks MRO’s position above Mars and automatically commands the orbiter to roll so the appropriate instrument points at the correct spot on the surface. At the same time, the algorithm commands the spacecraft’s solar arrays to rotate and track the Sun and its high-gain antenna to track Earth to maintain power and communications.

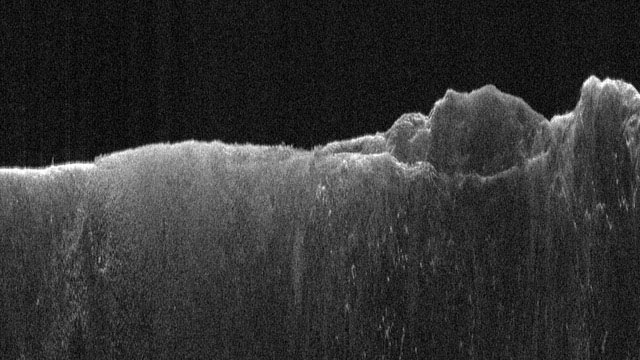

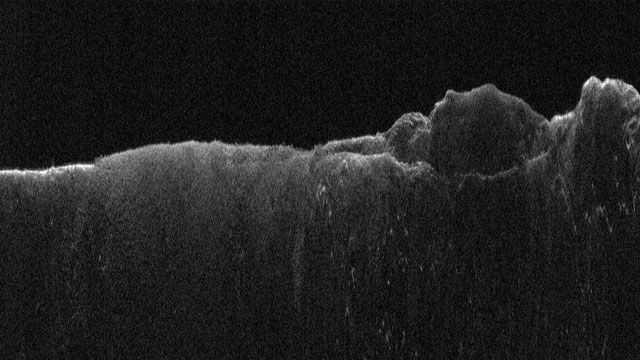

Very large rolls, which are 120 degrees, require even more planning to maintain the safety of the spacecraft. The payoff is that the new maneuver enables one particular instrument, called the Shallow Radar (SHARAD), to have a deeper view of Mars than ever before.

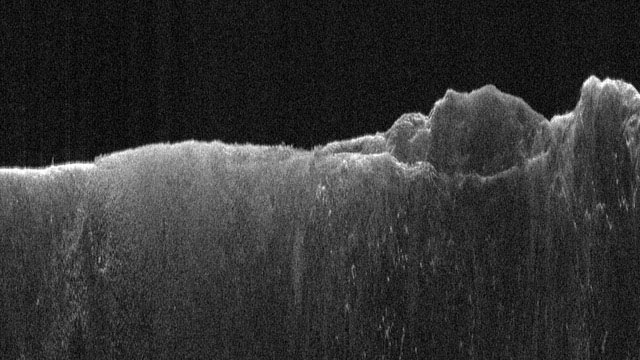

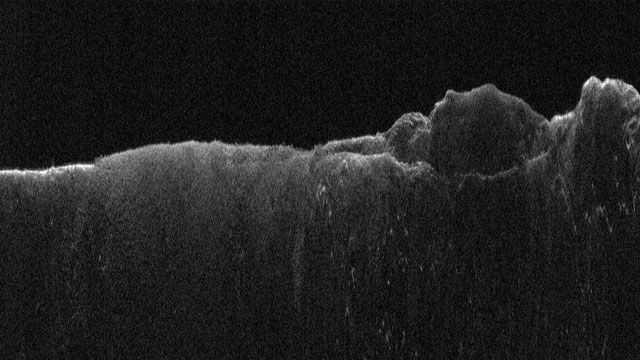

SHARAD’s View of Mars During a ‘Very Large Roll’

Bigger Rolls, Better Science

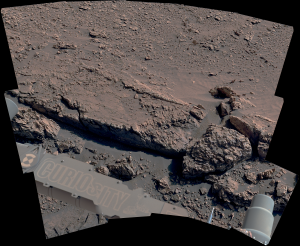

Designed to peer from about half a mile to a little over a mile (1 to 2 kilometers) belowground, SHARAD allows scientists to distinguish between materials like rock, sand, and ice. The radar was especially useful in determining where ice could be found close enough to the surface that future astronauts might one day be able to access it. Ice will be key for producing rocket propellant for the trip home and is important for learning more about the climate, geology, and potential for life at Mars.

But as great as SHARAD is, the team knew it could be even better.

To give cameras like the High-Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE) prime viewing at the front of MRO, SHARAD’s two antenna segments were mounted at the back of the orbiter. While this setup helps the cameras, it also means that radio signals SHARAD pings onto the surface below encounter parts of the spacecraft, interfering with the signals and resulting in images that are less clear.

“The SHARAD instrument was designed for the near-subsurface, and there are select regions of Mars that are just out of reach for us,” said Morgan, a co-investigator on the SHARAD team. “There is a lot to be gained by taking a closer look at those regions.”

In 2023, the team decided to try developing 120-degree very large rolls to provide the radio waves an unobstructed path to the surface. What they found is that the maneuver can strengthen the radar signal by 10 times or more, offering a much clearer picture of the Martian underground.

But the roll is so large that the spacecraft’s communications antenna is not pointed at Earth, and its solar arrays aren’t able to track the Sun.

“The very large rolls require a special analysis to make sure we’ll have enough power in our batteries to safely do the roll,” Thomas said.

Given the time involved, the mission limits itself to one or two very large rolls a year. But engineers hope to use them more often by streamlining the process.

Learning to Roll With It

While SHARAD scientists are benefiting from these new moves, the team working with another MRO instrument, the Mars Climate Sounder, is making the most of MRO’s standard roll capability.

The JPL-built instrument is a radiometer that serves as one of the most detailed sources available of information on Mars’ atmosphere. Measuring subtle changes in temperature over the course of many seasons, Mars Climate Sounder reveals the inner workings of dust storms and cloud formation. Dust and wind are important to understand: They are constantly reshaping the Martian surface, with wind-borne dust blanketing solar panels and posing a health risk for future astronauts.

Mars Climate Sounder was designed to pivot on a gimbal so that it can get views of the Martian horizon and surface. It also provides views of space, which scientists use to calibrate the instrument. But in 2024, the aging gimbal became unreliable. Now Mars Climate Sounder relies on MRO’s standard rolls.

“Rolling used to restrict our science,” said Mars Climate Sounder’s interim principal investigator, Armin Kleinboehl of JPL, “but we’ve incorporated it into our routine planning, both for surface views and calibration.”

More About MRO

NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California manages MRO for the agency’s Science Mission Directorate in Washington as part of its Mars Exploration Program portfolio. The SHARAD instrument was provided by the Italian Space Agency. Its operations are led by Sapienza University of Rome, and its data is analyzed by a joint U.S.-Italian science team. The Planetary Science Institute in Tucson, Arizona, leads U.S. involvement in SHARAD. Lockheed Martin Space in Denver built MRO and supports its operations.

For more information, visit:

science.nasa.gov/mission/mars-reconnaissance-orbiter

News Media Contacts

Andrew Good

Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif.

818-393-2433

andrew.c.good@jpl.nasa.gov

Karen Fox / Molly Wasser

NASA Headquarters, Washington

202-358-1600

karen.c.fox@nasa.gov / molly.l.wasser@nasa.gov

2025-084