100 years ago, the battle for television raged

How fire and rivalry shaped broadcasting’s debut. The post 100 years ago, the battle for television raged appeared first on Popular Science.

Television’s broadcast debut in 1936 unfolded like a plot made for the medium itself—complete with bitter competition, intrigue, celebration, and devastating setbacks. The story reached its climax when a fire at London’s Crystal Palace destroyed parts of television inventor John Logie Baird’s research laboratory on November 30, 1936. The timing could not have been worse. Baird was locked in a high-stakes showdown with his deep-pocketed rival, Electric and Musical Industries (EMI), who had partnered with wireless pioneer Guglielmo Marconi and the American radio giant RCA-Victor.

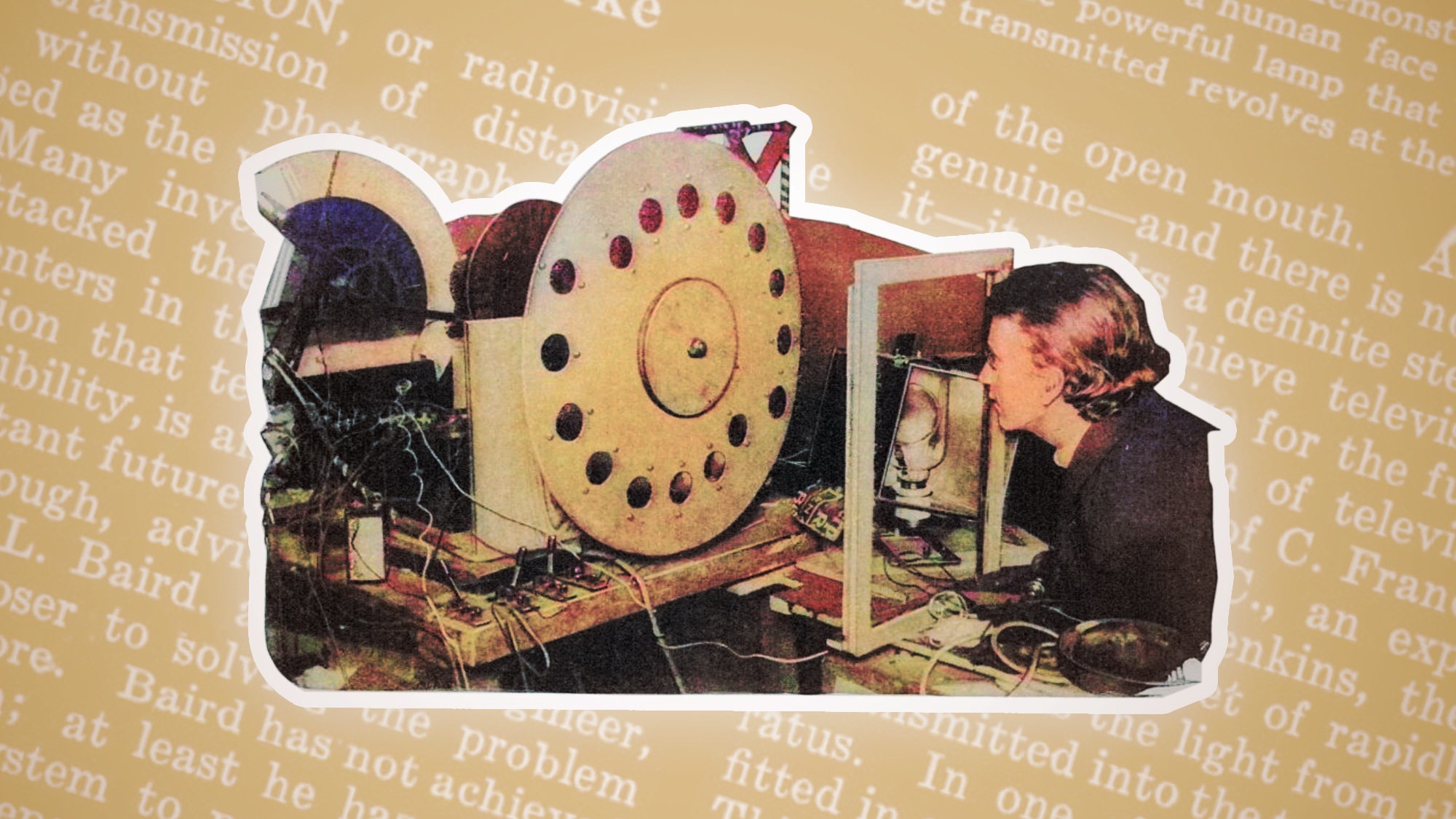

Long before that fateful November day, the television landscape was crowded with inventors competing for the title to the as-yet unproven but promising medium. Despite his eventual defeat, Baird deserves credit for achieving the first wireless transmission of a moving image, as Popular Science writer Newton Burke reported in June 1925. The discrepancy between Baird’s early success and later failure came down to a classic confrontation between old and new tech: Where Baird succeeded with mechanical television systems, he struggled to master the new and more efficient electronic technology.

Despite its mechanical design, Baird’s primitive television system was revolutionary for its time. Though it consisted of unwieldy components too impractical for commercial success, Burke noted that it successfully “transmitted the motions of a human face, winking and smiling, from one room of a laboratory to another, without the aid of photography or wires.” The transmitted image was so crude that Baird’s photographic evidence resembled the white hockey mask favored by serial killer Jason Voorhees in Friday the 13th films. Yet Burke recognized its significance, writing, “The fact remains that the outline of the face is plain, so are the shadows of the eye sockets and the shape of the open mouth.”

Baird’s achievement, while novel, built upon decades of previous work. His system incorporated ideas from Maurice LeBlanc, an engineer from France who published the first principles of television transmission systems in 1880’s “Etude sur la transmission électrique des impressions lumineuses,” or “Study on the electrical transmission of light impressions.” LeBlanc’s design was part of a six-volume engineering compilation devoted to the advent of electric lights, La Lumière Electrique, as reported by Popular Science in June 1882.

Baird also drew from the work of German inventor Paul Nipkow, who had developed an “electric telescope”—a pair of spinning discs capable of scanning still images and transmitting them through electric wires, which he patented in 1885. Meanwhile, Charles Jenkins, a Washington, D.C.-based contemporary, achieved the first synchronized video and audio transmission on June 13th, 1925, though his system only handled still pictures rather than motion.

Understanding Baird’s mechanical system helps explain both its breakthrough nature and ultimate limitations. His apparatus used a rapidly revolving disk equipped with lenses that focused light from the subject onto a selenium cell. This cell converted the light impulses into electrical signals suitable for radio transmission—crucial because radio waves were the only practical distribution medium available at the time. A synchronized receiving disk with a ground-glass screen then reconstructed the image.

As Burke explained, “The images received on his ground-glass screen are described as being made up of exceedingly fine lines of varying darkness.” However, the width of these lines and their flicker rate were constrained by the physical limitations of the mechanical apparatus—problems that would require electronic solutions to overcome.

While Baird perfected his mechanical approach, gradually improving display resolution from 30 to 240 lines by 1936—today’s displays are measured in pixels, 8K being the latest generation—other inventors pursued electronic television systems using cathode rays to scan and project images. This technological shift created one of the most bitter patent battles in broadcasting history. Philo Farnsworth, a farm boy from Utah, and Vladimir Zworykin, a Russian émigré who fled during the Russian Revolution, each claimed first rights.

While Farnsworth was officially awarded the first electronic television system patent in 1930, Zworykin had filed the first U.S. patent in 1923. Their rivalry sparked a long and rancorous legal showdown between Farnsworth and RCA, who had hired Zworykin to build America’s first broadcast television system, the National Broadcasting Company (NBC), which debuted at the 1939 New York World’s Fair.

In the years before NBC’s American debut, the center of television development was London, where the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) sought to upgrade beyond Baird’s crude broadcasts that had been running for nearly a decade. Recognizing an opportunity to accelerate progress, the BBC commissioned a head-to-head competition in 1936 between rival systems.

Baird’s team collaborated with Farnsworth to create a hybrid mechanical-electronic system, while EMI partnered with Marconi for transmission technology and RCA to leverage Zworykin’s electronic innovations. (By then the patent dispute had been settled, with RCA paying royalties to Farnsworth.) Both teams would broadcast identical programming from London’s Alexandra Palace, allowing direct comparison of their capabilities.

Even before the Crystal Palace fire, Baird faced an uphill battle. His system couldn’t match EMI’s superior 405-line resolution or transmission range. The devastating fire that destroyed his laboratory equipment proved to be the final setback. Shortly afterward, Baird abandoned his television work altogether.

John Logie Baird, the first person to wirelessly broadcast moving pictures, died in 1946 without any financial stake in what would become one of the 20th century’s most profitable industries. His mechanical breakthrough had paved the way for the electronic systems that would dominate broadcasting, but the rapid pace of technological change left him behind.

The post 100 years ago, the battle for television raged appeared first on Popular Science.

.png?#)