Tiny changes in the heart may cut irregular heartbeat risk

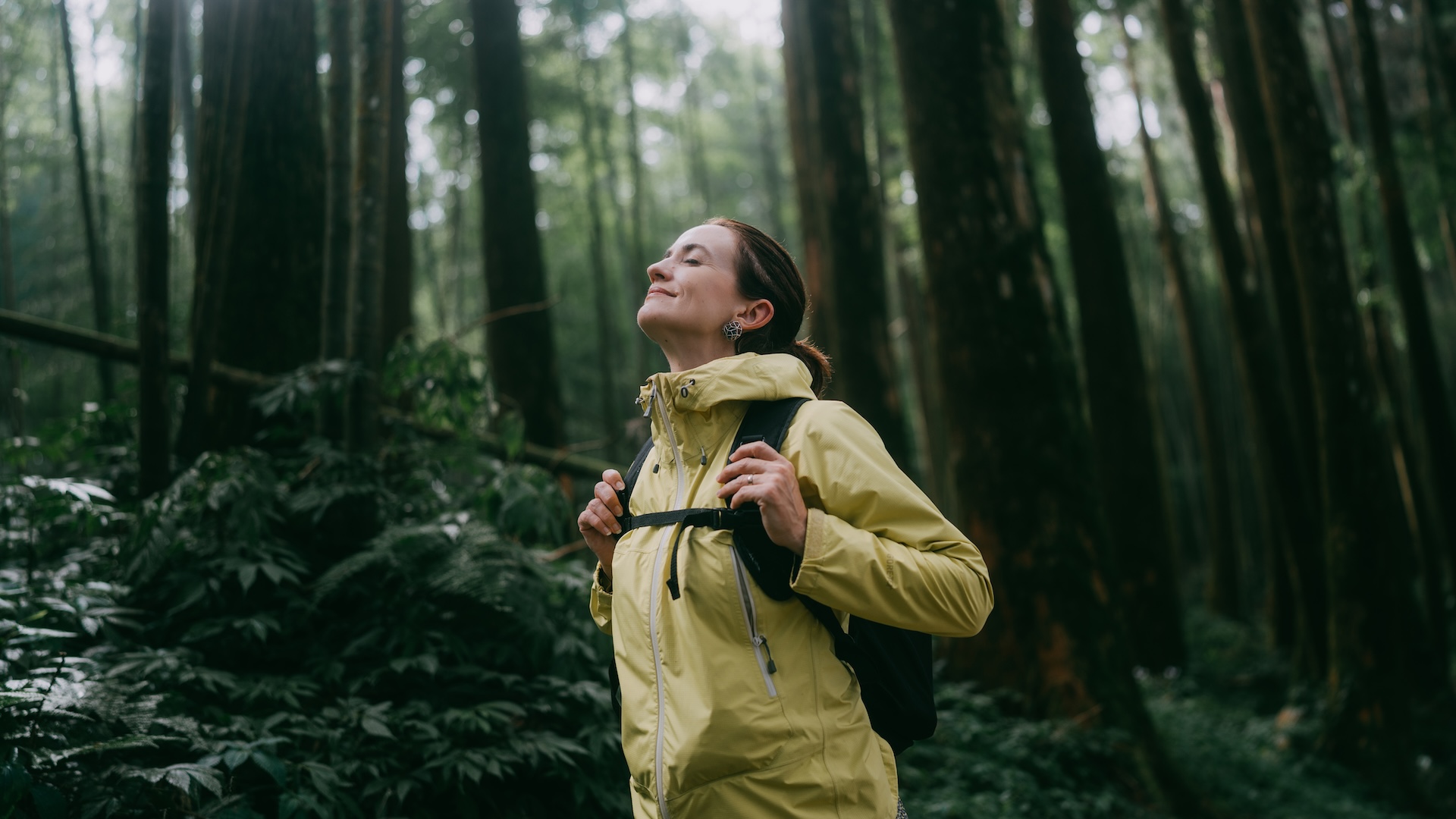

A new discovery challenges the idea that all age-related changes in the heart are harmful.

Researchers have found that microscopic structural changes in heart cells may help reduce arrhythmia risk.

Medically known as arrhythmias, irregular heartbeats become more common with age and can lead to health problems.

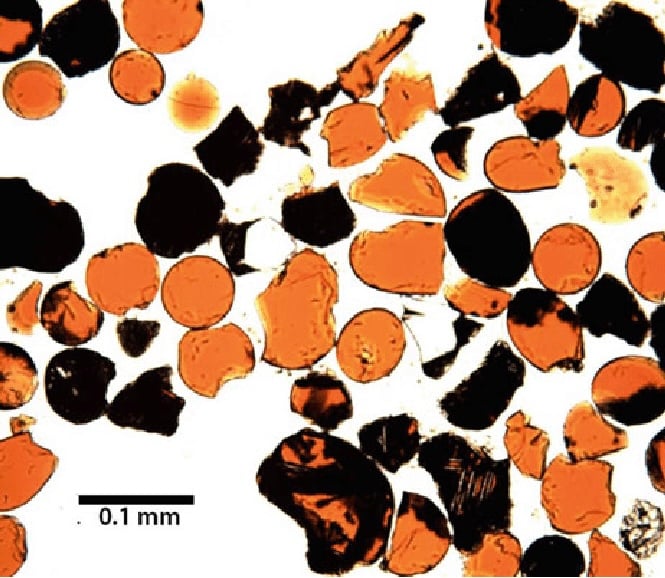

But a new study in JACC Clinical Electrophysiology, a journal of the American College of Cardiology, reveals that a tiny gap between heart cells called the perinexus naturally narrows with age—an adaptation that may help stabilize heart rhythm.

The discovery challenges the idea that all age-related changes in the heart are harmful.

“As we get older and cardiac cells get bigger, the body compensates by making electrical communications more robust,” says Steven Poelzing, a professor at the Fralin Biomedical Research Institute at Virginia Tech .

“Making sure the communication between cells remains high during aging appears to occur naturally to keep cardiovascular disease in check.”

Poelzing suggests that the body compensates for an aging heart by reinforcing the structure between cells to strengthen electrical communication and support the rapid influx of sodium ions that initiate each heartbeat.

Arrhythmias occur when the heart’s electrical signals become too fast, too slow, or disorganized. They affect millions worldwide and can range from harmless to life-threatening, increasing the risk of stroke, heart failure, and sudden cardiac arrest.

The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute reports that atrial fibrillation is the most common arrhythmia, affecting more than 2 million adults in the United States, with numbers expected to rise significantly.

To investigate how structural changes in the heart impact arrhythmia risk, researchers studied young and old guinea pig hearts, using medication to trigger a condition called sodium channel gain of function.

They found that older hearts naturally had a narrower perinexus, which appeared to protect against arrhythmias. However, when this space was artificially widened, older hearts quickly developed irregular rhythms, while younger hearts remained stable.

As heart cells grow larger with age, they adhere more tightly, maintaining electrical stability.

“If you can keep cells nicely packed, you can conceal a lot of age-associated cardiac pathologies,” says Poelzing, who is also a professor in the biomedical engineering and mechanics department in the Virginia Tech College of Engineering.

He compared it with a house’s foundation: If the foundation is solid, the structure can tolerate wear and tear elsewhere. But if the foundation is unstable, the whole structure is at greater risk.

From a clinical perspective, Poelzing says this study also sheds light on why arrhythmias can be difficult to detect in aging patients.

Cardiologists refer to some heart diseases as “concealed” because the body naturally compensates for electrical instability—returning to normal function before a problem can be caught on standard tests. This is why doctors often rely on long-term monitoring to detect arrhythmias before the heart re-stabilizes the issue.

An accompanying editorial in JACC: Clinical Electrophysiology comments on the study, describing the delicate, “push-and-pull” balance between the perinexus size and electrical activity in the heart. The editorial also highlights the broader significance of the findings, suggesting that targeting perinexus size could offer new strategies for preventing arrhythmias and improving heart health as people age.

Additional researchers from Virginia Tech and Ohio State University contributed to the work.

The research was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Virginia Tech

The post Tiny changes in the heart may cut irregular heartbeat risk appeared first on Futurity.

.png?#)