Wild boars began shrinking down to domesticated pigs 8,000 years ago

Ancient pig teeth indicate that the farm animals were first domesticated in China. The post Wild boars began shrinking down to domesticated pigs 8,000 years ago appeared first on Popular Science.

While some humans may slander pigs as dirty, messy, lazy animals, others celebrate these intelligent animals that have a long history in agriculture. Some roughly 8,000-year-old pig teeth now offer evidence that the mammals were first domesticated from wild boar in South China. It also indicates that these pigs were eating humans’ cooked foods and waste–evidence that has eluded archeologists. The findings are detailed in a study published June 9 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

For years, archaeologists and anthropologists have considered present-day China as the likely location for pig domestication. This process is mostly associated with the Neolithic period about 10,000 years ago, as humans generally began to transition from foraging to farming.

Both 10,000 years ago and today, wild boars are large and aggressive mammals that live fairly independently. They are native to Asia, parts of North Africa, and most of Europe, but are now found in parts of North America, South America, and Oceania. They typically live in forests, where they root for food from the undergrowth. Compared to domestic pigs, wild boars have larger heads and mouths, and bigger teeth.

“While most wild boars are naturally aggressive, some are more friendly and less afraid of people, which are the ones that may live alongside humans,” Jiajing Wang, a study co-author and anthropologist at Dartmouth, said in a statement. “Living with humans gave them easy access to food, so they no longer needed to maintain their robust physiques. Over time, their bodies became smaller, and their brains also became smaller by about one-third.”

When studying the domestication of pigs and other animals, archaeologists have often relied on examining the sizes and shapes of their bones in order to track the morphological changes to their skeletons over time. According to Wang, this can be problematic since that reduction in body size likely occurred later in the domestication process.

“What probably came first were behavioral changes, like becoming less aggressive and more tolerant of humans,” said Wang.

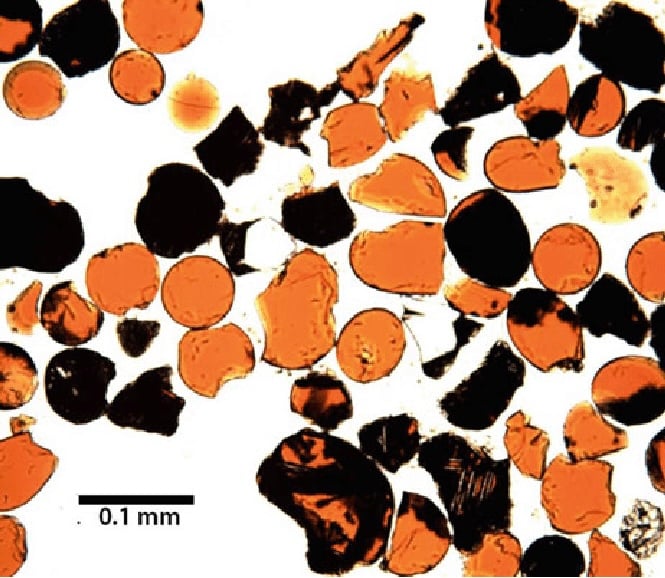

In this new study, the team tried a different method using microfossil analysis on teeth and documented what the pigs had been eating over their lifespan. They used the molar teeth of 32 pig specimens from two of the earliest known sites where humans lived 8,000 years ago–Jingtoushan and Kuahuqiao in the Lower Yangtze River region of South China. These sites were waterlogged, which helped preserve the organic materials–including mineralized dental plaque called dental calculus.

The analysis revealed that 240 starch granules were present within the teeth. The pigs had eaten cooked foods—including yams and rice—in addition to an unidentified tuber, acorns, and wild grasses.

“These are plants that were present in the environment at that time and were found in human settlements,” says Wang.

[ Related: Gladiator bones finally confirm human-lion combat in Roman Europe. ]

Previous studies found rice at both sites with intensive rice cultivation at Kuahuqiao. This spot is located farther inland and has greater access to freshwater than coastal-based Jingtoushan. Other research has shown starch residues in grinding stones and pottery from Kuahuqiao.

“We can assume that pigs do not cook food for themselves, so they were probably getting the food from humans either by being fed by them and/or scavenging human food,” said Wang.

An additional clue provided some evidence of human presence–the eggs of a human parasite specifically, those of a whipworm named Trichuris. These parasite eggs can mature inside of human digestive systems and they were found in the pig dental calculus. The brownish yellow, football-shaped parasite eggs were found in 16 of the pig teeth. This indicates that the pigs must have been eating human feces or drinking water or eating food with dirt contaminated by human feces.

The team also conducted a statistical analysis of the dental structures of the pig specimens from Kuahuqiao and Jingtoushan. Some had small teeth similar to those seen in modern domestic populations in China.

“Wild boars were probably attracted to human settlements as people started settling down and began growing their own food,” said Wang. “These settlements created a large amount of waste, and that waste attracts scavengers for food, which in turn fosters selection mechanisms that favored animals willing to live alongside humans.”

This process called a commensal pathway in animal domestication occurs when the animal is attracted to human settlements, instead of humans actively trying to recruit the animals. The data also supports that early interactions involved domestic pigs under active human management. This represents a prey pathway in the domestication process in addition to a commensal one.

“Our study shows that some wild boars took the first step towards domestication by scavenging human waste,” said Wang.

This study adds another piece of the puzzle of pig domestication and how parasitic diseases may have been spread in these early human communities.

The post Wild boars began shrinking down to domesticated pigs 8,000 years ago appeared first on Popular Science.

.png?#)