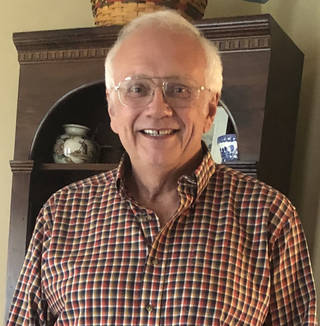

Interview with Michiharu Hyogo, Citizen Scientist and First Author of a New Scientific Paper

Peer-reviewed scientific journal articles are the bedrock of science. Each one represents the culmination of a substantial project, impartially checked for accuracy and relevance – a proud accomplishment for any science team. The person who takes responsibility for writing the paper must inevitably and repeatedly write, edit, and rewrite its content as they receive comments […]

9 min read

Interview with Michiharu Hyogo, Citizen Scientist and First Author of a New Scientific Paper

Peer-reviewed scientific journal articles are the bedrock of science. Each one represents the culmination of a substantial project, impartially checked for accuracy and relevance – a proud accomplishment for any science team.

The person who takes responsibility for writing the paper must inevitably and repeatedly write, edit, and rewrite its content as they receive comments and constructive criticism from colleagues, peers, and editors. And the process involves much more than merely re-writing the words. Implementing feedback and polishing the paper regularly involves reanalyzing data and conducting additional analyses as needed, over and over again. The person who successfully climbs this mountain of effort can then often earn the honor of being named the first author of a peer-reviewed scientific publication. To our delight, more and more of NASA’s citizen scientists have taken on this demanding challenge, and accomplished this incredible feat.

Michiharu Hyogo is one of these pioneers. His paper, “Unveiling the Infrared Excess of SIPS J2045-6332: Evidence for a Young Stellar Object with Potential Low-Mass Companion” (Hyogo et al. 2025) was recently accepted for publication in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. He conceived of the idea for this paper, performed most of the research using of data from NASA’s retired Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission, and submitted it to the journal. We asked him some questions about his life and he shared with us some of the secrets to his success.

Q: Where do you live, Michi?

A: I have been living in Tokyo, Japan since the end of 2012. Before that, I lived outside Japan for a total of 21 years, in countries such as Canada, the USA, and Australia.

Q: Which NASA Citizen Science projects have you worked on?

A: I am currently working on three different NASA-sponsored projects: Disk Detective, Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, and Planet Patrol.

Q: What do you do when you’re not working on these projects?

A: Until March of last year, I worked as a part-time lecturer at a local university in Tokyo. At the moment, I am unemployed and looking for similar positions. My dream is to work at a community college in the USA, but so far, my job search has been unsuccessful. In the near future, I hope to teach while also working on projects like this one. This is my dream.

Q: How did you learn about NASA Citizen Science?

A: It’s a very long story. A few years after completing my master’s degree, around 2011, a friend from the University of Hawaii (where I did my bachelor’s degree) introduced me to one of the Zooniverse projects. Since it was so long ago, I can’t remember exactly which project it was—perhaps Galaxy Zoo or another one whose name escapes me.

I definitely worked on Planet Hunters, classifying all 150,000 light curves from (NASA’s) Kepler observatory. Around the time I completed my classifications for Planet Hunters, I came across Disk Detective as it was launching. A friend on Facebook shared information about it, stating that it was “NASA’s first sponsored citizen science project aimed at publishing scientific papers”.

At that time, I was unemployed and had plenty of free time, so I joined without giving much thought to the consequences. I never expected that this project would eventually lead me to write my own paper — it was far beyond anything I had imagined.

Q: What would you say you have gained from working on these NASA projects?A: Working on these NASA-sponsored projects has been an incredibly valuable experience for me in multiple ways. Scientifically, I have gained hands-on experience in analyzing astronomical data, identifying potential celestial objects, and contributing to real research efforts. Through projects like Disk Detective,Backyard Worlds: Planet 9, and Planet Patrol, I have learned how to systematically classify data, recognize patterns, and apply astrophysical concepts in a practical setting.

Beyond the technical skills, I have also gained a deeper understanding of how citizen science can contribute to professional research. Collaborating with experts and other volunteers has improved my ability to communicate scientific ideas and work within a research community.

Perhaps most importantly, these projects have given me a sense of purpose and the opportunity to contribute to cutting-edge discoveries. They have also led to unexpected opportunities, such as co-authoring scientific papers — something I never imagined when I first joined. Overall, these experiences have strengthened my passion for astronomy and my desire to continue contributing to the field.

Q: How did you make the discovery that you wrote about in your paper?

A: Well, the initial goal of this project was to discover circumstellar disks around brown dwarfs. The Disk Detective team assembled more than 1,600 promising candidates that might possess such disks. These objects were identified and submitted by volunteers from the same project, following the physical criteria outlined within it.

Among these candidates, I found an object with the largest infrared excess and the fourth-latest spectral type. This was the moment I first encountered the object and found it particularly interesting, prompting me to investigate it further.

Although we ultimately did not discover a disk around this object, we uncovered intriguing physical characteristics, such as its youth and the presence of a low-mass companion with a spectral type of L3 to L4.

Q: How did you feel when your paper was accepted for publication?

A: Thank you for asking this question—I truly appreciate it. I feel like the biggest milestone of my life has finally been achieved!

This is the first time I genuinely feel that I have made a positive impact on society. It feels like a miracle. Imagine if we had a time machine and I could go back five years to tell my past self this whole story. You know what my past self would say? “You’re crazy.”

Yes, I kept dreaming about this, and deep down, I was always striving toward this goal because it has been my purpose in life since childhood. I’m also proud that I accomplished something like this without being employed by a university or research institute. (Ironically, I wasn’t able to achieve something like this while I was in grad school.)

I’m not sure if there are similar examples in the history of science, but I’m quite certain this is a rare event.

Q: What would you say to other citizen scientists about the process of writing a paper?

A: Oh, there are several important things I need to share with them.

First, never conduct research entirely on your own. Reach out to experts in your field as much as possible. For example, in my case, I collaborated with brown dwarf experts from the Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 team. When I completed the first draft of my paper, I sent it to all my collaborators to get their feedback on its quality and to check if they had any comments on the content. It took some time, but I received a lot of helpful suggestions that ultimately improved the clarity and conciseness of my paper.

If this is your first time receiving extensive feedback, it might feel overwhelming. However, you should see it as a valuable opportunity—one that will lead you to stronger research results. I am truly grateful for the feedback I received. This process will almost certainly help you receive positive feedback from referees when you submit your own paper. That’s exactly what happened to me.

Second, do not assume that others will automatically understand your research for you. This seems to be a common challenge among many citizen scientists. First, you must have a clear understanding of your own research project. Then, it is crucial to communicate your progress clearly and concisely, without unnecessary details. If you have questions—especially when you are stuck — be specific.

For example, I frequently attend Zoom meetings for various projects, including Backyard Worlds: Planet 9 and Disk Detective. In every meeting, I give a brief recap of what I’ve been working on — every single time — to refresh the audience’s memory. This helps them stay engaged and remember my research. (Screen sharing is especially useful for this.) After the recap, I present my questions. This approach makes it much easier for others to understand where I am in my research and, ultimately, helps them provide potential solutions to the challenges I’m facing.

Lastly, use Artificial Intelligence (AI) as much as possible. For tasks like editing, proofreading, and debugging, AI tools can be incredibly helpful. I don’t mean to sound harsh, but I find it surprising that some people still do these things manually. In many cases, this can be a waste of time. I strongly believe we should rely on machines for tasks that we either don’t need to do ourselves or simply cannot do. This approach saves time and significantly improves productivity.

Q: Thank you for sharing all these useful tips! Is there anything else you would like to add?

A: I would like to sincerely thank all my collaborators for their patience and support throughout this journey. I know we have never met in person, and for some of you, this may not be a familiar way to communicate (it wasn’t for me at first either). If that’s the case, I completely understand. I truly appreciate your trust in me and in this entirely online mode of communication. Without your help, none of what I have achieved would have been possible.

I am now thinking about pushing myself to take on another set of research projects. My pursuit of astronomical research will not stop, and I hope you will continue to follow my journey. I will also do my best to support others along the way.