We finally know how parrots ‘talk’

Budgie brains reveal parallels between parrot and human speech. The post We finally know how parrots ‘talk’ appeared first on Popular Science.

Parrots are so adept at mimicking people that the avian moniker has become synonymous with repetition. Yet for as long as we’ve known about the birds’ incredible ability for impressions, how they manage such complex and flexible vocalizations has been a mystery. A new study offers a piece of the puzzle by peeking into the parakeet brain, and finds remarkable similarities to the human neural region that controls speech.

The research, published March 19 in the journal Nature, suggests parrots (and specifically parakeets) could be a model for studying human speech, helping scientists to better understand and treat speech disorders. It also adds to the growing stack of scientific findings that demonstrate “bird-brained” isn’t much of an insult after all. Many of our feathered friends show impressive memory, learning, counting, and reasoning abilities. This newest study underscores that–when it comes to talking–humans are all somewhat bird- (or at least budgie-) brained, and we should be proud.

Common parakeets, also known as budgerigars or budgies, are a small, neon green and yellow species of Australian parrot often sold as pets. In the wild, they live in social flocks, communicating via long warble songs, eating seeds, and flying in groups to wherever the next best meal is likely to be. In captivity, they’re known to keep up their social tendencies by copying human phrases. Puck, a pet budgerigar who lived until 1994, stands as the current Guinness World Record Holder for the bird with the largest vocabulary, at an impressive 1,728 words.

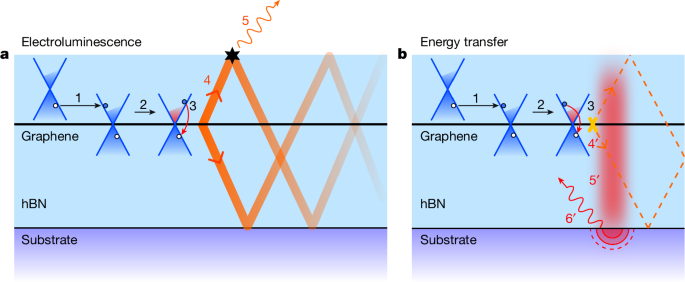

To understand how these birds accurately imitate people and produce so many distinct sounds, the study authors surgically implanted tiny probes into four parakeets’ brains in a particular region linked to the syrinx, the avian vocal organ. Then, they collected neural activity from each bird as it vocalized. They compared the budgie data with that from humans and zebra finches, songbirds commonly used in scientific research that have a less flexible vocal repertoire than parakeets.

They found the parakeet brain region they focused on, called the anterior arcopallium (AAC), operates more similarly to parts of the human cortex linked to speech-motor function than the equivalent zebra finch region. In the zebra finches, vocalizations seem to be coded by complex, uninterpretable arrays of neuron activity. Each sound has a unique brain ‘barcode’ that accompanies it. Zebra finches learn and repeat intricate songs, but their brain activity suggests they have limited ability to alter what they’ve learned or improvise.

Looking at the zebra finch brain waves, “we can’t make heads or tails of it,” says Michael Long, study co-author and a neuroscientist at the NYU Grossman School of Medicine. “We see no hint of the actual notes that those birds are singing,” he tells Popular Science. “We may see activity, and that activity is the same every time those birds sing their songs, but there’s no clear kind of sheet music for the song.

In contrast, both budgie and human brains work in a more modular fashion. Birds and people appear to encode vocalization through discreet, repeatable neural pathways. In the human brain, specific lip or tongue muscle movements are associated with certain neuron patterns. The connections are clear enough that scientists have previously used these types of brain signals to interpret and reproduce intended speech in people who’ve lost the ability to actually talk themselves.

Similarly, in the parakeet AAC, neurons fire in accordance with the tone and type of sound a bird makes, says Long. “It’s a kind of vocal keyboard,” he explains. “Individual brain cells seem to be driving consonant sounds and vowel sounds. Even within the vowels, there’s a whole spectrum of different pitches that they can achieve. We find B-flat cells, we find B-cells–all across the musical register…With all of those combined, you can basically code up whatever you want to say.”

Budgie neural activity is so closely aligned with the chirps, warbles, and calls the birds produce that Long and his co-researchers could chart the undulating frequency of a call based on the signals of five neurons alone, with near exact precision. It’s the first time that this sort of brain to speech configuration has been catalogued in a non-human species, Long notes.

The observations offer “exciting avenues for future research,” writes Joshua Neunuebel, a neuroscientist at the University of Delaware who wasn’t involved in the study, in an accompanying perspective piece.

In follow-up work, Long and his co-researchers hope to go beyond the AAC and uncover the higher order brain regions that might be playing the proverbial keyboard keys inside budgie brains. How, for instance, does a bird opt to make certain sounds over others? He’s also collaborating with machine learning researchers with the intent of “translating” what the parakeets are communicating via their vocalizations.

Yet one of the most promising veins of future research lies in the possibility of using parakeets as a model organism to study all of the many things that can go wrong with human speech–from Autism-related deficits to Parkinson’s Disease and aphasia.

“Such studies hold promise for advancing speech therapies and inspiring brain–computer interface technologies,” writes Neunuebel. Parakeet and human brains may be separated by 300 million years of evolution, but the strikingly convergent neurological system that allows both us and budgies to speak could offer scientists a way to test interventions and treatments for speech loss, and better understand disease progression.

“This gets me out of bed in the morning, thinking about how to really help people whose voices have been taken away,” Long says.

The post We finally know how parrots ‘talk’ appeared first on Popular Science.