What happens when our brain goes blank

Humans experience an empty mind up to 20 percent of the time. The post What happens when our brain goes blank appeared first on Popular Science.

My thoughts often feel like endless streams of information. That’s until someone asks me the name of a stranger I met six or seven seconds before, and my mind goes blank. Mind blanking is much more common than you might think. Researchers think that our minds are blank somewhere between 5 and 20 percent of the time. Neuroscientists face significant hurdles in adding color and detail to the mystery of an empty mind, but new research is trying to establish the edges of these formless thoughts.

Defining the blank mind

Athena Demertzi, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of Liège, recently published a review paper on mind-blanking research. The field has struggled to agree on what the term means–Demertzi’s paper lists no fewer than seven different definitions. Her preferred view is that mind blanking is about “the impression of having no thoughts or not being able to report any thoughts.”

This interpretation is intentionally vague, as people can use all kinds of language to self-report a mind blank. Examples include “I don’t remember what I was thinking” or “I wasn’t paying attention.” Demertzi says that this can trip up researchers who attempt to incorporate other brain processes, such as memory, into their work.

Within this broad definition, Demertzi then works to separate different strands of mind blanking. This work is fraught with complications. One of the most reliable tools for examining the brain’s inner workings is functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Demertzi explains that fMRI researchers often ask their volunteers to “think of nothing” while in the scanner. Doing so causes activation along the midline of the brain in regions like the cingulate cortex, says Demertzi. However, rather than being a marker of a blank mind, this signal is a cognitive marker of the effort required to suppress thoughts.

A signal behind mind blanking

To block out this signal, Demertzi tried a different strategy. In a 2023 study, her team monitored the brains of people at rest in a scanner. At random intervals, participants were asked to report what they had been thinking of. The team then analyzed the brain activity patterns in the seconds preceding their response. The brains of individuals who reported blank minds showed a distinct signal, a pattern involving a momentary synchronization of brain networks. “They are all deactivated,” says Demertzi. This signal is also seen during sleep or anesthesia, she adds.

This finding is supported by other research that has established a strong link between mind blanking and the level of stimulation our brains are experiencing, called arousal. When arousal levels are low, mind-blanking episodes are more likely to occur. This is suggested to be because high arousal is necessary to keep up a continuous stream of thought.

There may be a cost to keeping up a very high state of arousal, however. At high levels, this focus tips over into anxiety, which inhibits performance. Demertzi’s paper points out that these anxious states can lead to racing thoughts that may blur individual ideas and make them hard to recall–another form of mind blanking.

Mind blanking and ADHD

In certain cases, mind blanking can even be a feature of clinical conditions. “We know that it manifests in clinical states like ADHD,” says Demertzi. Unmedicated kids with ADHD report mind blanking at a higher rate than kids without the condition. Other conditions that feature racing thoughts, like generalized anxiety disorder, also include mind blanking as a related feature.

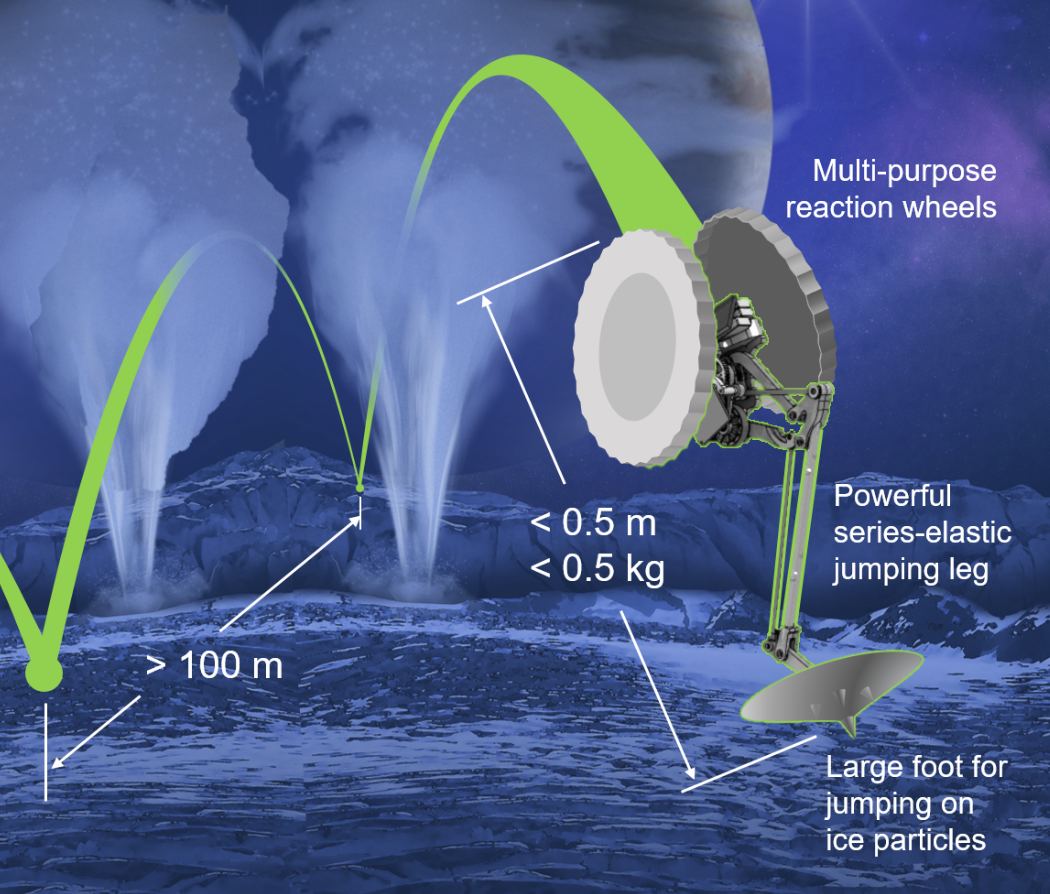

The ultimate question for Demertzi is why mind blanking happens in the first place. Researchers are still trying to figure this out, although she suggests that the link to sleep and arousal may be a hint. “When we sleep,” says Demertzi, “Our neurons are getting rest by throwing away what has been accumulated throughout the day through the glymphatic system.”

Demertzi says that this toxin-clearing function–which is disputed by some sleep neuroscientists–may also occur in brief periods while we are awake. We notice these “pit stops” in cognition as mind blanks. Ultimately, these blanks may be a way our brain maintains high function for the rest of our waking experience. “How can you sustain a continuous wakeful life if our brains are not helping a bit?” says Demertzi.

The post What happens when our brain goes blank appeared first on Popular Science.