Soil carbon credits emerge from the ‘trough of disillusionment’

Indigo Ag, Boomitra and other project developers are planning on issuing millions of tons of credits annually. The post Soil carbon credits emerge from the ‘trough of disillusionment’ appeared first on Trellis.

Key takeaways

- After years of slow growth, issuances are on a tear.

- More data and better models are helping win over skeptical buyers.

- Soil carbon credits are now a viable option for many, but some environmental groups remain wary.

Just five years ago, the idea of locking away carbon dioxide in farmland soils was one of the hottest areas in carbon markets. New startups were entering the field and major companies, including JPMorgan Chase and IBM, were purchasing soil carbon credits.

That momentum all but disappeared as questions surfaced about the science behind the idea and projects took longer than expected to be approved. But the work quietly continued and the field appears to have turned a corner, with a flurry of credits issued in recent months. Indeed, 2025 might be the year when soil carbon begins to deliver on its promise.

“The sector has gone through its own Gartner hype cycle,” said Aadith Moorthy, CEO of Boomitra, a soil carbon project developer. “2024 was probably the trough of disillusionment. We are recovering from the trough right now.”

Moorthy was referring to the cycle of inflated and then dashed expectations that emerging technologies often pass through as they mature. In the case of soil carbon, the hype rested on the enormous promise of regenerative agriculture techniques, including cover crops and reduced tillage, to sequester carbon. In 2019, scientists estimated that farmland soils in the U.S. alone could draw down 250 million tons of carbon dioxide annually.

Scalable solution

Carbon markets promised to provide the funding farmers needed to deploy those techniques, prompting a burst of startup activity around the start of the decade. But getting projects validated by Verra and other major registries took longer than expected. Some environmental organizations, notably the World Resources Institute, also questioned the mitigation potential of regenerative agriculture. Amid the delays and doubts, Nori, a prominent soil sequestration startup, shut down last September. CIBO, another company that sold coil carbon credits, is now pursuing different lines of business in agriculture.

But other project developers have been able to ride out the downtimes. Although the scientific debate continues, it’s widely agreed that the models used to estimate soil carbon levels have improved, in part because project developers are continually collecting soil samples to help ground the estimates. “It’s gone from science fair to a scalable kind of solution,” said Ewan Lamont, head of sustainability solutions at Indigo Ag, one of the original project developers.

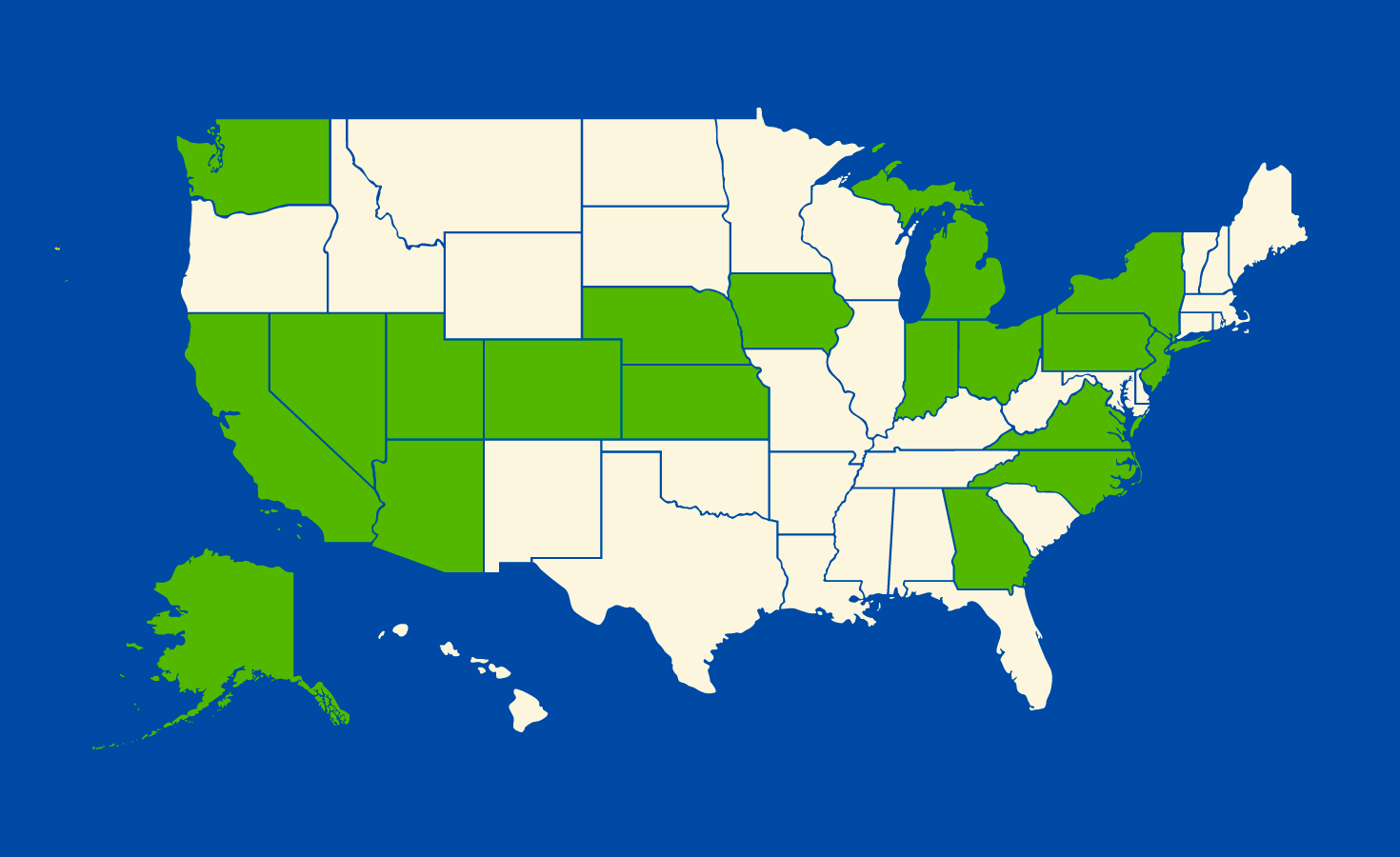

Indigo’s first batch of soil carbon credits, issued in 2022, totaled 20,000 tons of CO2 removed from the atmosphere. It’s third crop, released in 2024, received an important vote of confidence when Microsoft, by far the largest buyer of removal credits, purchased 40,000 tons. The company’s most recent issuance, announced last month, was for 630,000 credits, bringing the total the company claims to have stored in U.S. farmlands to almost a million tons. The most recent credits cost between $60 and $80 per ton, said Lamont.

One of Indigo’s rivals is Boomitra, which works with farmers in lower-income countries. The company issued its first batch of 47,000 cropland credits from smallholder farms in India last month. A second issuance of around 300,000 will follow later this year, added Moorthy. Because costs are lower in India, Boomitra’s credits sell for less than $40, he noted.

Beyond the ‘regen curious’

Both companies are now targeting scale. Lamont identified $100 per ton as a “catalytic” price that would unlock interest that goes beyond the “regen curious” U.S. producers that have been the first adopters of cover crops and other techniques. Indigo currently has around 1,000 farmers and 7 million acres enrolled, which leaves huge potential for expansion. Lamont noted that cover crops, as an example, are planted on less than 10 percent of U.S. cropland: “So you’ve got a phenomenal opportunity to really drive that as an economic practice.”

Moorthy agrees. “We see significant volumes coming to market from India, East Africa, Brazil and Argentina over the next few years,” he said. “We could scale to 20 million tons per year.”

New entrants are also aiming high: Agreena, a startup working with more than 2,000 farmers in Europe, plans to make its first release this summer and hopes to issue 2 million credits from its first two years of projects, said Michael Bertelsen, Agreena’s head of pricing, structuring and broker distribution.

Growth will depend on drawing more buyers into market, some of whom will likely remain wary of soil carbon credits. Carbon can be released from soils if farmers abandon regenerative methods or suffer floods, and monitoring millions of acres for such “reversals” is challenging. “I don’t think soil carbon makes sense as an offset mechanism because of the longevity,” said Christophe Jospe, a Nori co-founder who left the company in 2021 and now consults for food and agriculture companies.

Insurance measures

The industry’s answer to Jospe’s criticism rests in large part on remote sensing and scale. It’s impractical to monitor millions of acres through site visits, so soil carbon project developers use satellite imagery to check if a producer’s claim to have used cover crops is legitimate or to determine whether a no-till commitment has been maintained.

The companies and the carbon credit registries they use also create “buffer pools” to protect against reversals. In Indigo’s case, said Lamont, the registry it works with — the Climate Action Reserve — holds on to 14 percent of the credits it approves. If a reversal takes places and carbon is released back into the atmosphere, those tons are removed from this buffer. Indigo holds back another 5 percent as additional insurance, said Lamont.

Those measures appear to be winning over some previously skeptical buyers, but many environmental organizations remain unconvinced. “Companies present soil carbon sequestration as a key component of regenerative agriculture, although its potential in agricultural soils is heavily debated, and permanence of such removals is limited,” the non-profit NewClimate Institute concluded in a report published last year.

Those doubts might be addressed by better data on the impacts of regenerative methods, together with evidence that insurance mechanisms such as buffer pools prove effective. But the ongoing concerns suggest project developers still have much to do. In the Gartner hype cycle, technologies that get past the trough of disillusionment reach the “plateau of productivity.” “I don’t think we’re at the plateau yet,” said Moorthy. “I think there’s some heavy lifting to be done to get us in that.”

The post Soil carbon credits emerge from the ‘trough of disillusionment’ appeared first on Trellis.