NASA Aims to Fly First Quantum Sensor for Gravity Measurements

Researchers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, private companies, and academic institutions are developing the first space-based quantum sensor for measuring gravity. Supported by NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office (ESTO), this mission will mark a first for quantum sensing and will pave the way for groundbreaking observations of everything from petroleum reserves to […]

Researchers from NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, private companies, and academic institutions are developing the first space-based quantum sensor for measuring gravity. Supported by NASA’s Earth Science Technology Office (ESTO), this mission will mark a first for quantum sensing and will pave the way for groundbreaking observations of everything from petroleum reserves to global supplies of fresh water.

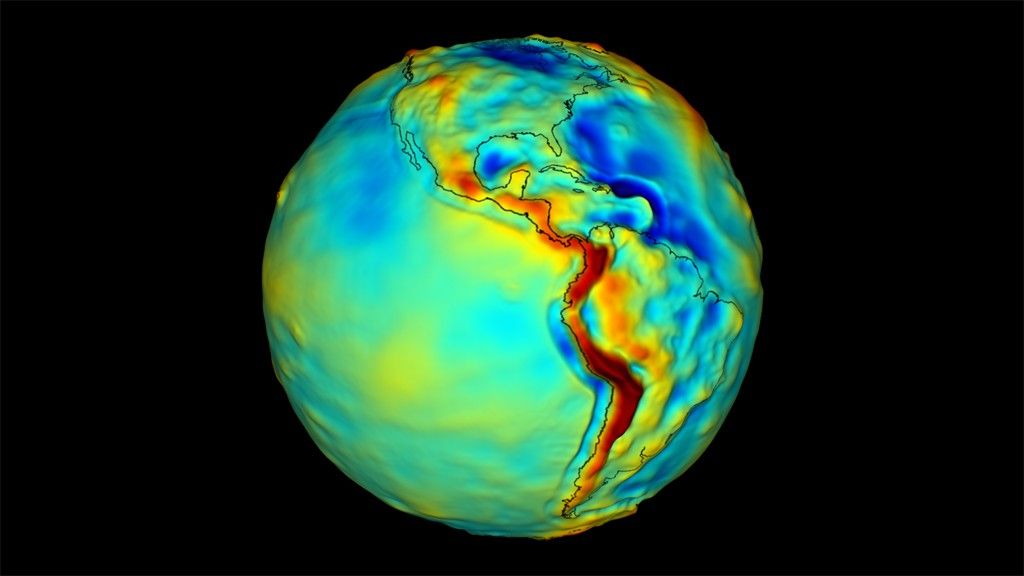

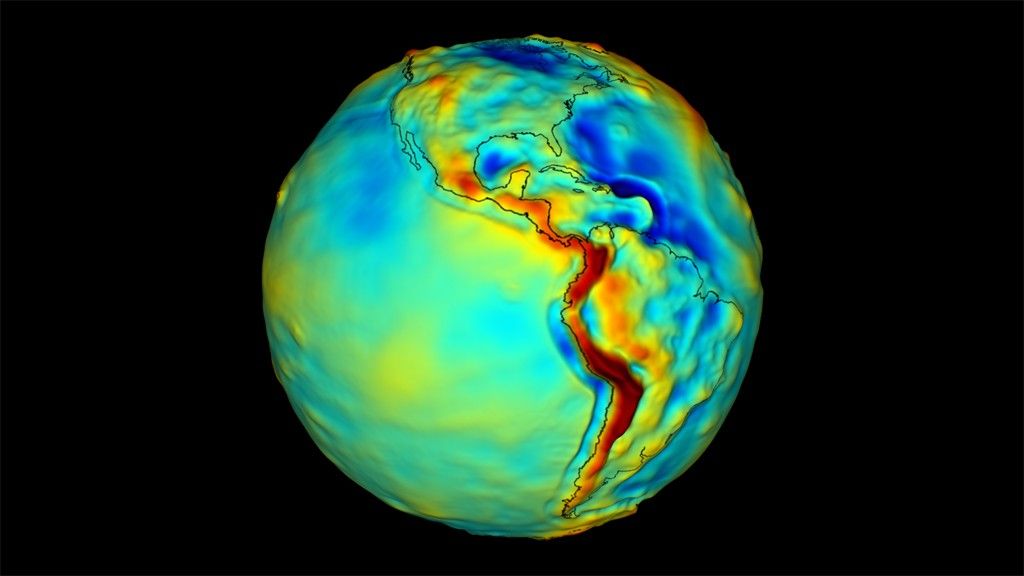

Earth’s gravitational field is dynamic, changing each day as geologic processes redistribute mass across our planet’s surface. The greater the mass, the greater the gravity.

You wouldn’t notice these subtle changes in gravity as you go about your day, but with sensitive tools called gravity gradiometers, scientists can map the nuances of Earth’s gravitational field and correlate them to subterranean features like aquifers and mineral deposits. These gravity maps are essential for navigation, resource management, and national security.

“We could determine the mass of the Himalayas using atoms,” said Jason Hyon, chief technologist for Earth Science at JPL and director of JPL’s Quantum Space Innovation Center. Hyon and colleagues laid out the concepts behind their Quantum Gravity Gradiometer Pathfinder (QGGPf) instrument in a recent paper in EPJ Quantum Technology.

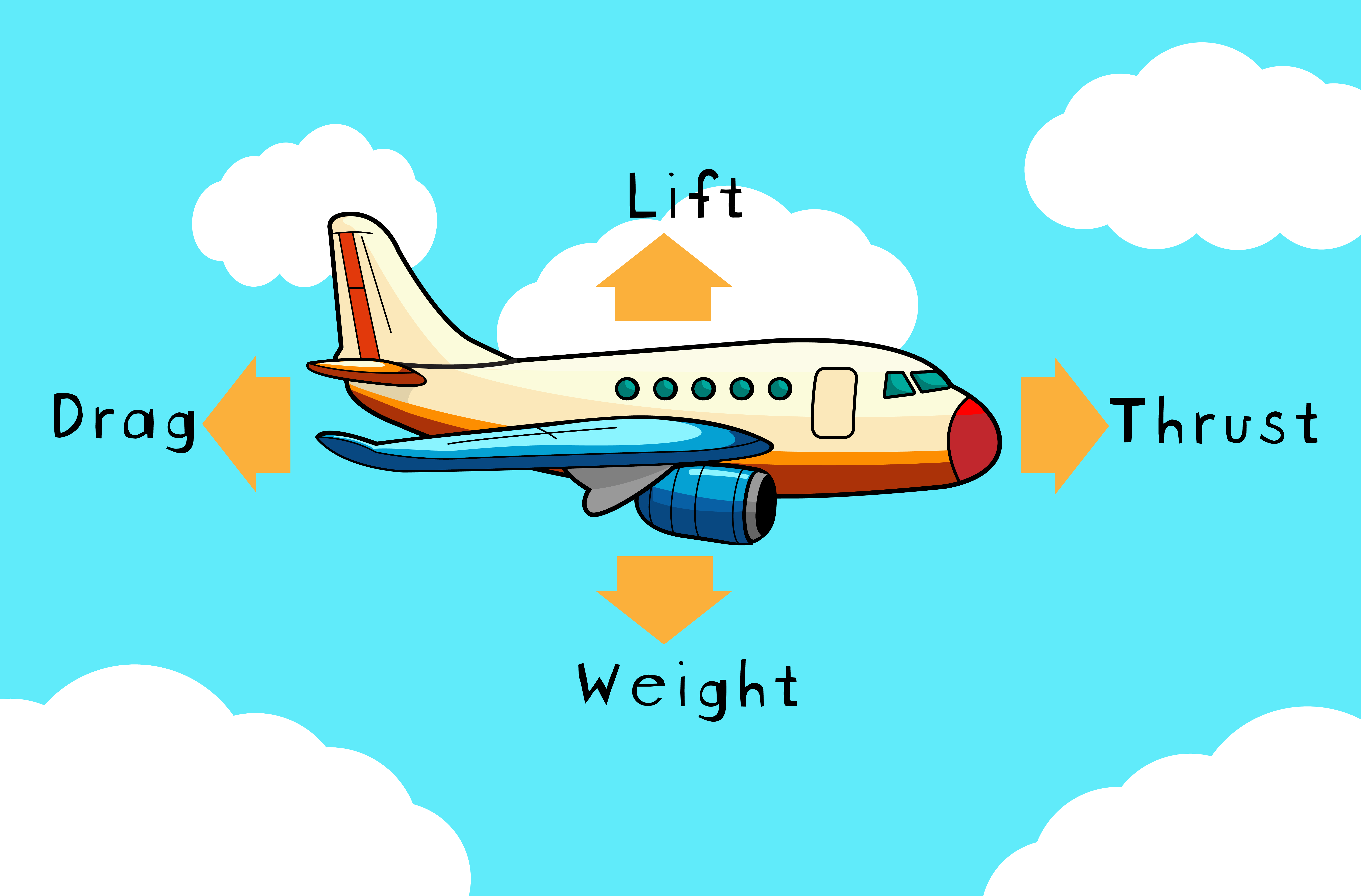

Gravity gradiometers track how fast an object in one location falls compared to an object falling just a short distance away. The difference in acceleration between these two free-falling objects, also known as test masses, corresponds to differences in gravitational strength. Test masses fall faster where gravity is stronger.

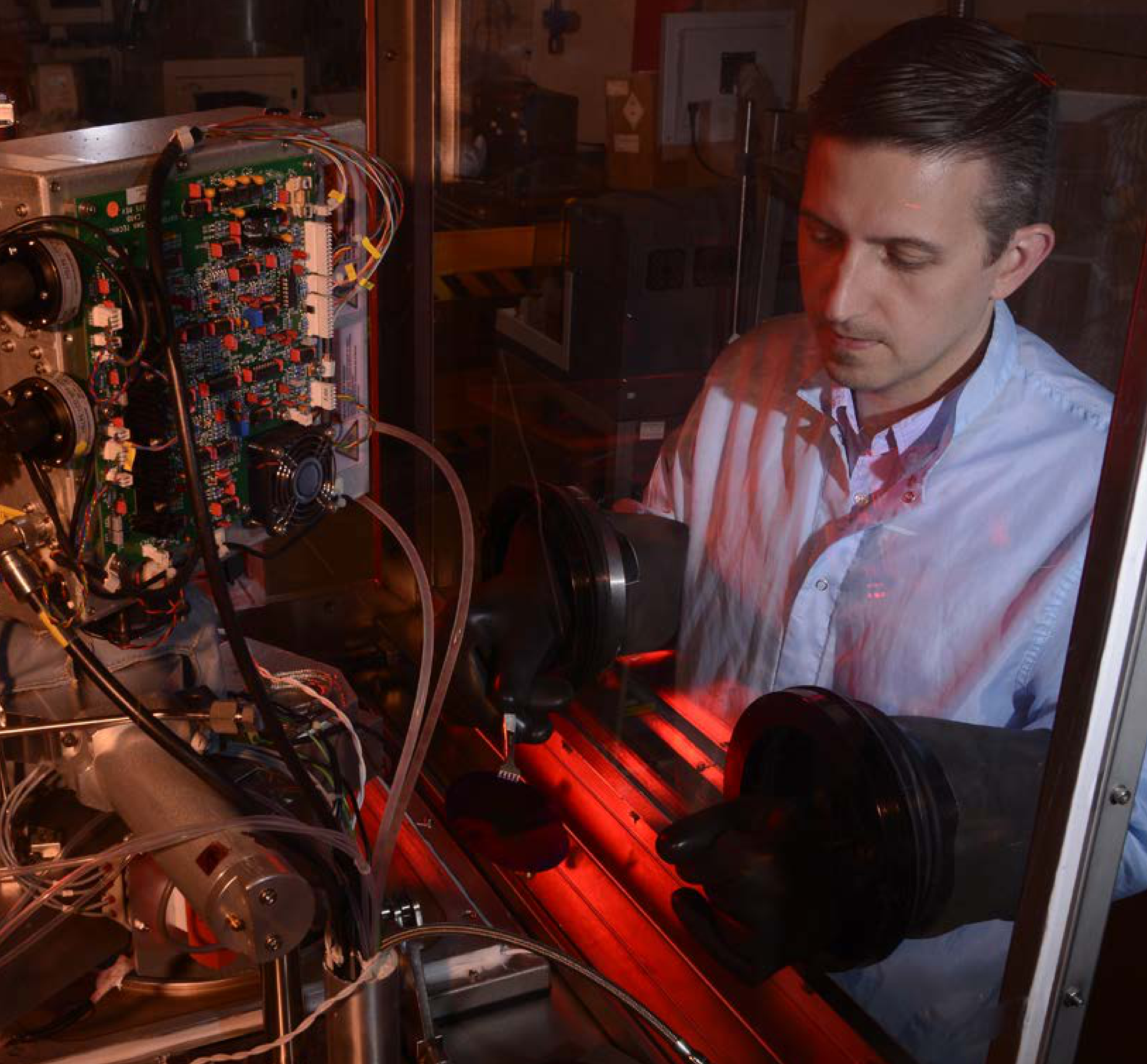

QGGPf will use two clouds of ultra-cold rubidium atoms as test masses. Cooled to a temperature near absolute zero, the particles in these clouds behave like waves. The quantum gravity gradiometer will measure the difference in acceleration between these matter waves to locate gravitational anomalies.

Using clouds of ultra-cold atoms as test masses is ideal for ensuring that space-based gravity measurements remain accurate over long periods of time, explained Sheng-wey Chiow, an experimental physicist at JPL. “With atoms, I can guarantee that every measurement will be the same. We are less sensitive to environmental effects.”

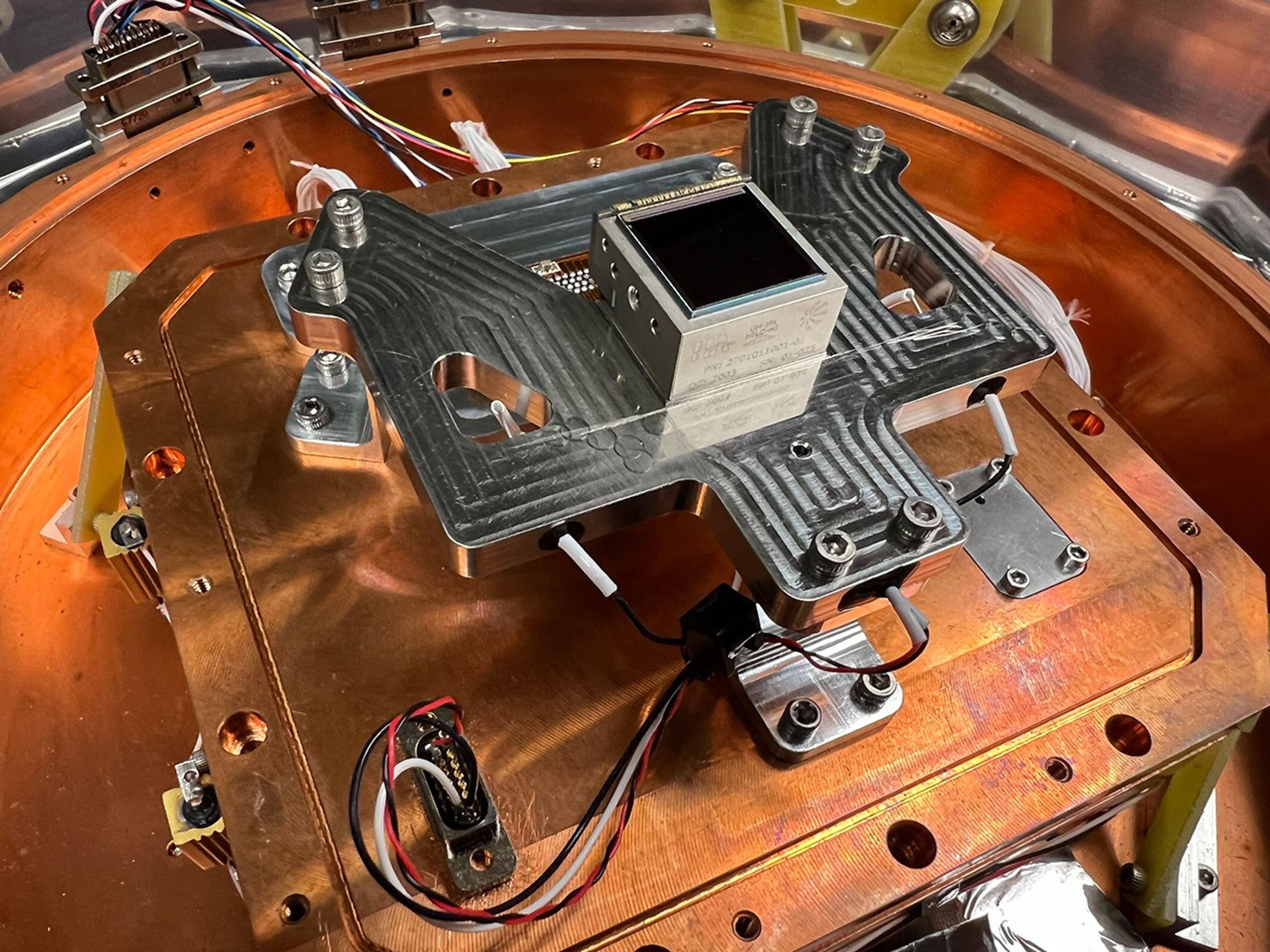

Using atoms as test masses also makes it possible to measure gravity with a compact instrument aboard a single spacecraft. QGGPf will be around 0.3 cubic yards (0.25 cubic meters) in volume and weigh only about 275 pounds (125 kilograms), smaller and lighter than traditional space-based gravity instruments.

Quantum sensors also have the potential for increased sensitivity. By some estimates, a science-grade quantum gravity gradiometer instrument could be as much as ten times more sensitive at measuring gravity than classical sensors.

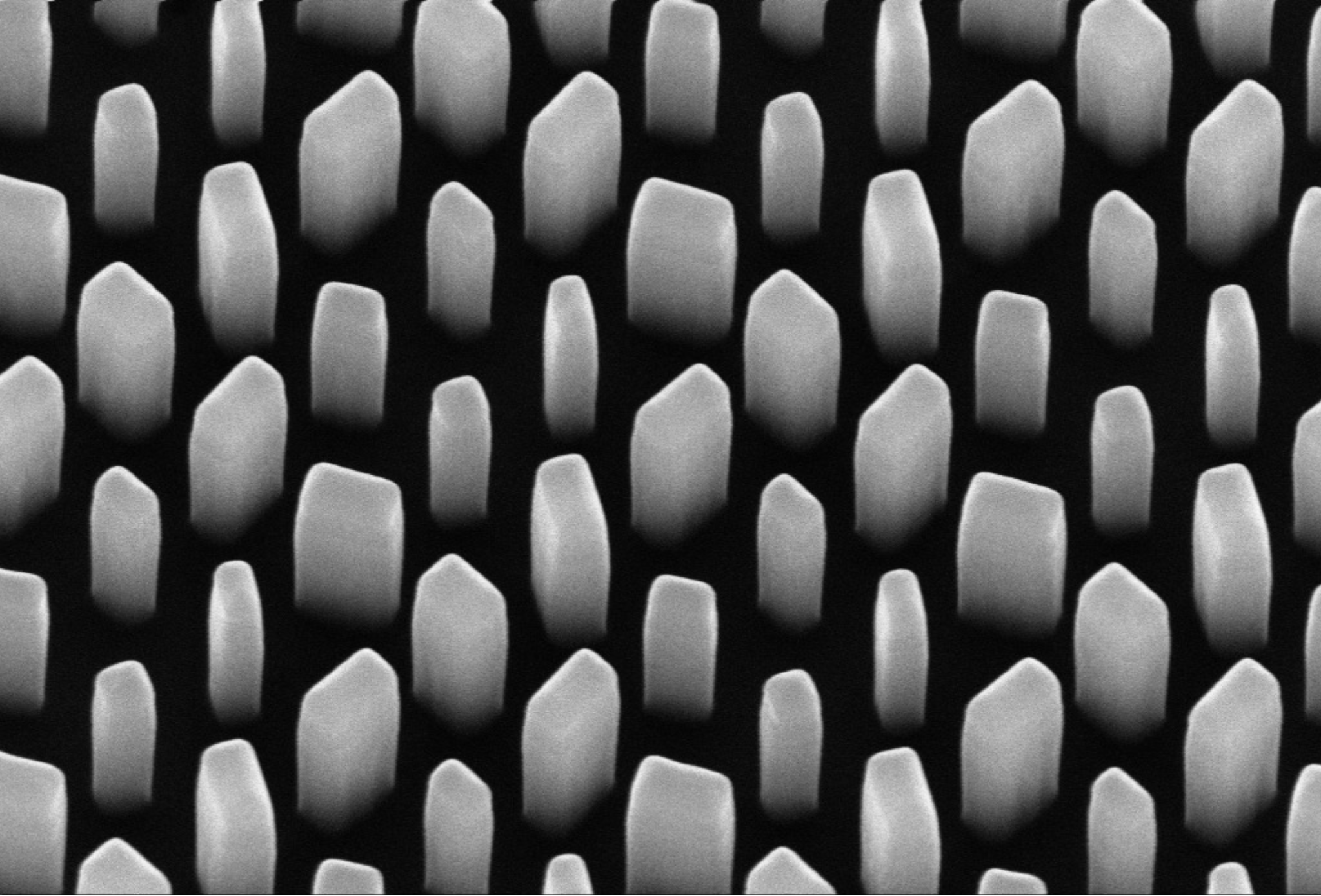

The main purpose of this technology validation mission, scheduled to launch near the end of the decade, will be to test a collection of novel technologies for manipulating interactions between light and matter at the atomic scale.

“No one has tried to fly one of these instruments yet,” said Ben Stray, a postdoctoral researcher at JPL. “We need to fly it so that we can figure out how well it will operate, and that will allow us to not only advance the quantum gravity gradiometer, but also quantum technology in general.”

This technology development project involves significant collaborations between NASA and small businesses. The team at JPL is working with AOSense and Infleqtion to advance the sensor head technology, while NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland is working with Vector Atomic to advance the laser optical system.

Ultimately, the innovations achieved during this pathfinder mission could enhance our ability to study Earth, and our ability to understand distant planets and the role gravity plays in shaping the cosmos. “The QGGPf instrument will lead to planetary science applications and fundamental physics applications,” said Hyon.

To learn more about ESTO visit: https://esto.nasa.gov

![The breaking news round-up: Decagear launches today, Pimax announces new headsets, and more! [APRIL FOOL’S]](https://i0.wp.com/skarredghost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lawk_glasses_handson.jpg?fit=1366%2C1025&ssl=1)