How your brain reacts to buying groceries can reveal your politics

Can grocery purchases help you spot a Republican or a Democrat? Yes, if you have a brain scanner, researchers report.

A new study reveals that how your brain reacts to food purchasing decisions can be used to determine your political affiliation with almost 80% accuracy.

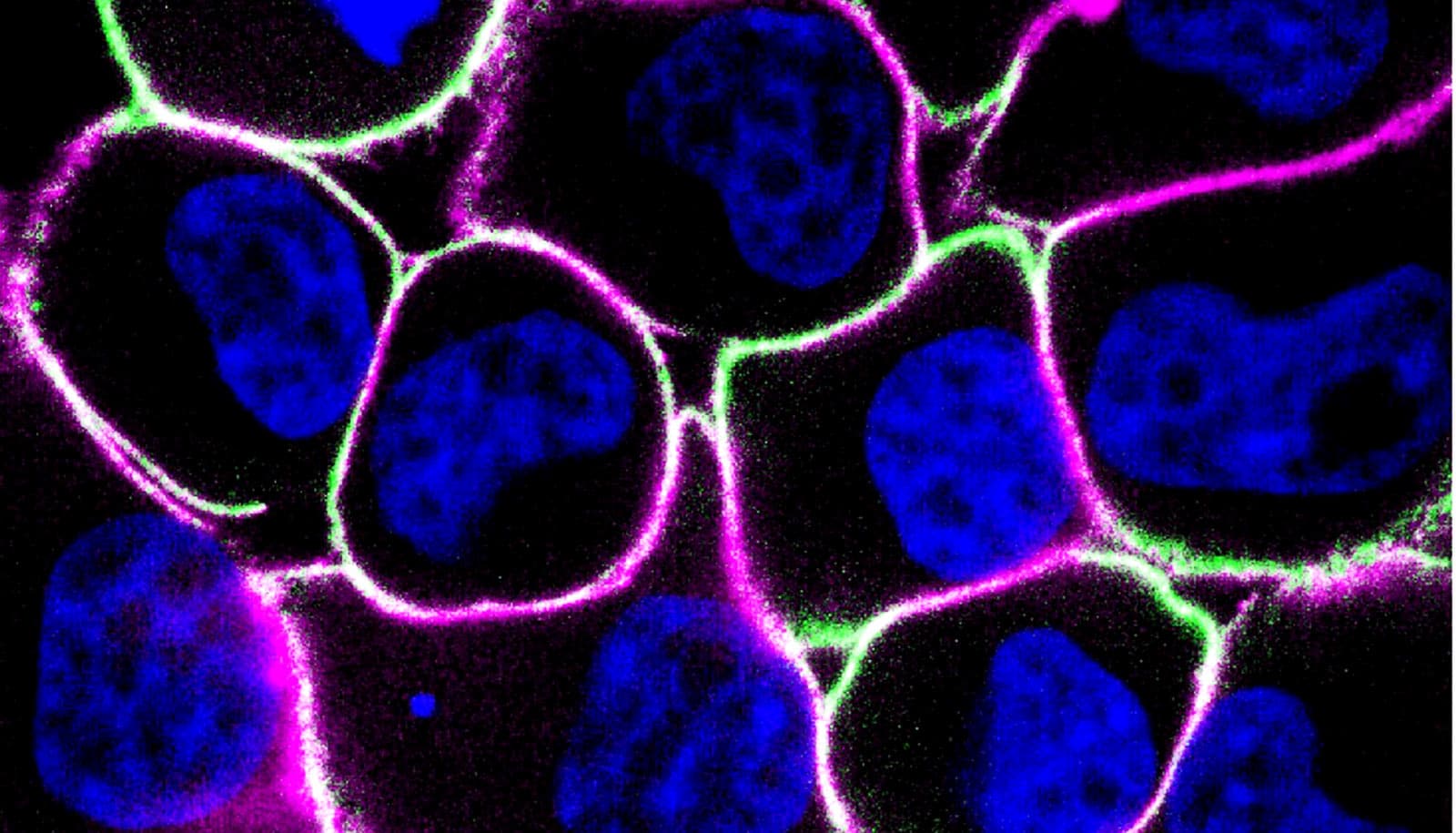

Researchers used brain imaging techniques to examine adults purchasing eggs and milk with various prices and produced in different ways.

Interestingly, the purchases did not significantly differ by the adults’ political party. What differed by political affiliation were the areas of the brain that were active during the purchases.

“Oversimplifying this a bit,” says John Crespi, a professor of economics at Iowa State and one of the researchers on the study, “you cannot tell whether someone is a Democrat or a Republican when you see them buy free-range eggs, but if you were to examine their brain activity, you would see that they are using different parts of their brains in that decision. The brain activity predicts the party, not the purchase.”

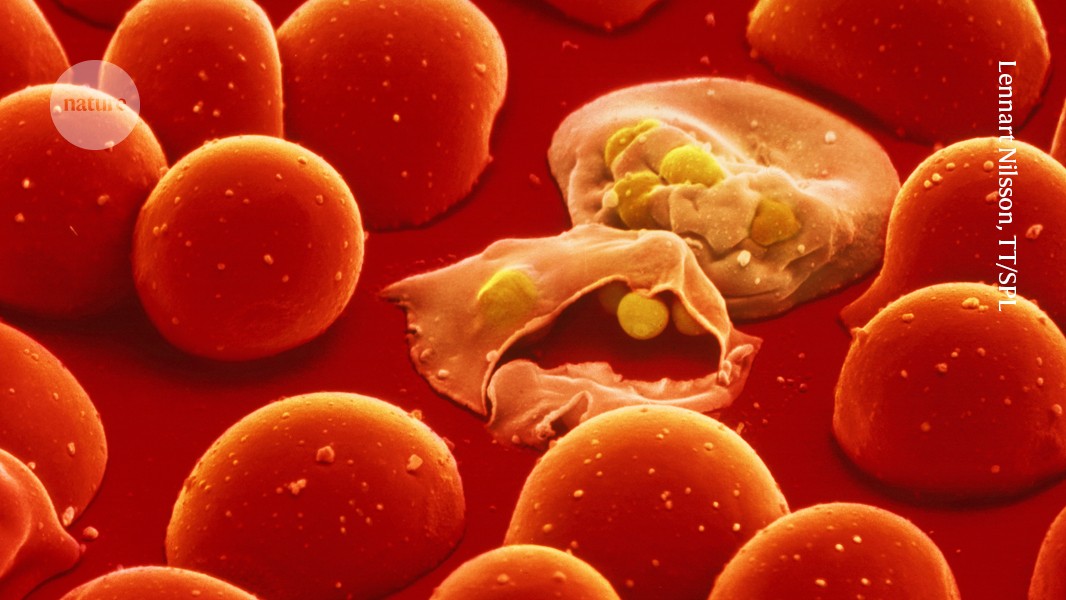

Coauthor Darren Schreiber adds, “We know from studies of twins that about 50% of your political ideology is biologically heritable and that data from your parents allows us to infer your political party with 69% accuracy. So, it is pretty amazing that just the signal from the brain while you’re buying eggs and milk enables us to correctly classify your political party about 80% of the time.”

As participants made their decisions, an fMRI scanner recorded activity in several areas of the brain including the ventromedial prefrontal cortex. While Crespi cautions against over-simplifying what different brain regions are responsible for, he does note that “the ventromedial prefrontal cortex is associated with a lot of what we might call economic decision making—where you are valuing one object over another not necessarily in a dollar sense, but in how you intrinsically value choices.”

What the researchers found was that while self-reported Democrats and Republicans may often make the same purchasing decisions, they could determine participants’ political affiliation with a high level of accuracy based on their brain activity while they made the decision.

“We can discern your likelihood of being in one party or another from how those brain regions react to what you are choosing even if the choices end up being exactly the same as someone in a different party,” Crespi says.

“I think that is what is intriguing—we can’t tell if you’re a Democrat by the eggs you buy, but by the parts of the brain you use to buy the eggs.”

That it was an actual purchasing decision was also important—previous research shows that study participants sometimes make decisions contrary to their real-world decisions when asked to make purely hypothetical decisions.

“We gave the subjects $50 but they were told that one of the products they selected would be given to them at the end of the study and its price would be deducted from their $50,” Crespi says.

“So, they went home with either a jug of milk or a carton of eggs and whatever money they had left after the purchase.”

The researchers chose to use milk and eggs in the study because they wanted common grocery items that were indistinguishable by brand, as branding can make purchasing decisions more personal and changes the way we think about them.

“We also wanted products that have had changes to their production practices, things we could add to the label that might influence the purchase, not just changes in prices—free range eggs, for example,” Crespi says.

The recent politicization of egg prices in the United States did not influence the study results, Crespi says.

“We actually did the study 10 years ago. We’ve published something like six or seven papers, but we’re only now getting around to this paper,” he says. “Because the data were so expensive to gather and because there is so much information that gets recorded in a brain scan, we’re trying to do as much with the data as we can.”

The findings from this study, Crespi says, would more than likely be applicable to other purchasing decisions.

“I would be amazed to find that the results do not hold up with other product choices—the parts of your brain that are active when buying a carton of eggs are active when other decisions are made,” he says.

Crespi also says that he thinks their study adds to a small but growing literature in political science and economics on brain activity and political ideology.

“My coauthor Darren Schreiber’s work was some of the first in this area showing differences seem to be there,” he says. “There are so few studies on politics and purchasing decisions that also look at brain activity that I’m kind of excited to say this is really a first.

“There are a few other studies that are in the same spirit, and our predictions hold up when compared with theirs although they did not look at the food choices like we did. The brain is still very much a mystery and papers like this are just like dipping our toes into a very big ocean,” he says.

The research appears in Politics and the Life Sciences.

Additional researchers from Iowa State University, the University of Kansas Medical Center, Oklahoma State University, and the University of Exeter in England contributed to the work.

Source: Iowa State University

The post How your brain reacts to buying groceries can reveal your politics appeared first on Futurity.

.jpg?#)