French startup aims to recycle 300 million pieces of polyester clothing a year

Reju plans to harness its parent company's polyester expertise to build up circular textile supply chains. The post French startup aims to recycle 300 million pieces of polyester clothing a year appeared first on Trellis.

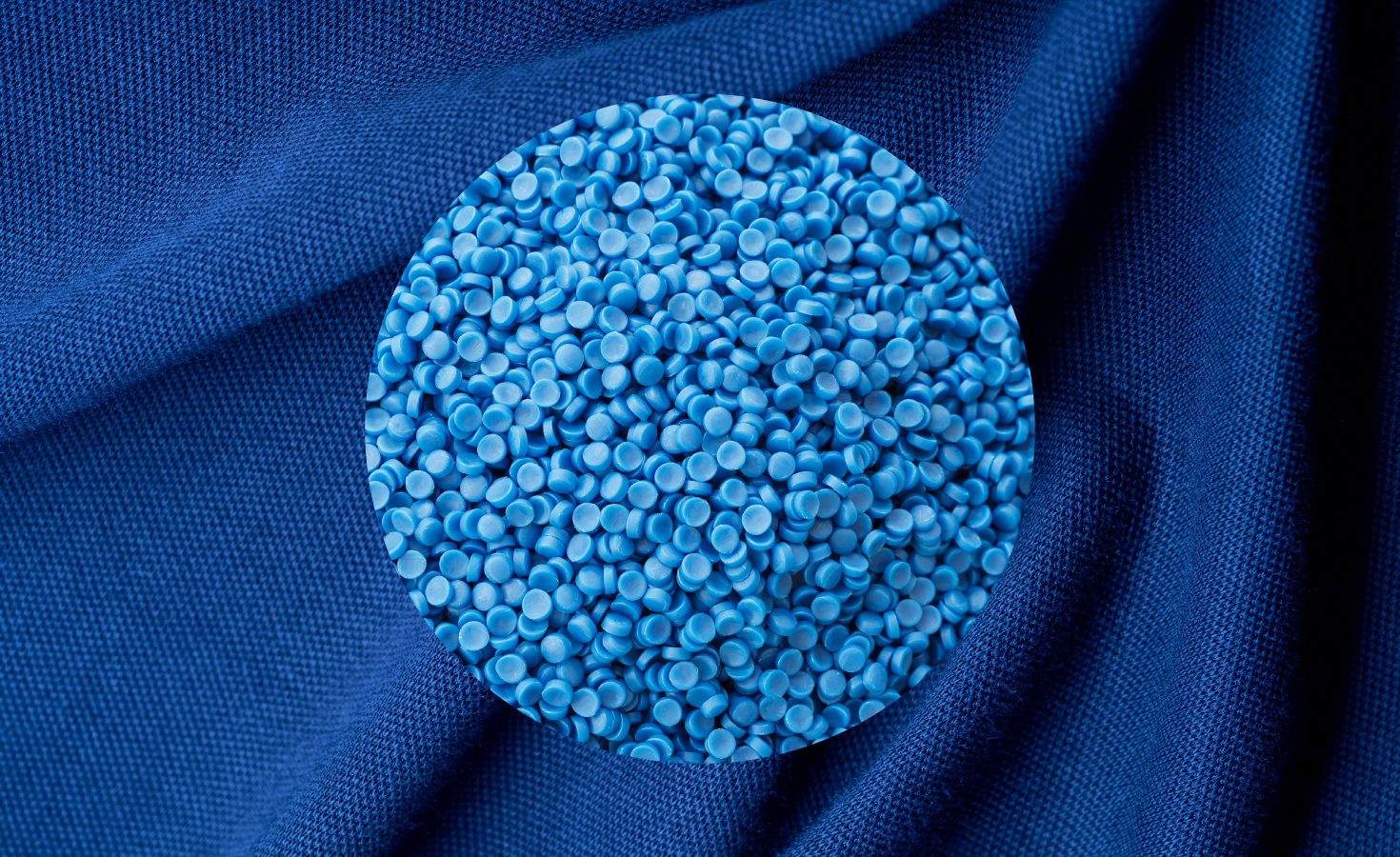

The race to commercialize apparel recycling is heating up. On May 20, Reju, a startup within a French engineering and fossil fuel company, announced plans to build a polyester recycling plant in the Netherlands. Its projected annual output: 300 million articles of clothing.

Since its launch 18 months ago, Reju has opened a “Regeneration Hub Zero” demonstration plant in Frankfurt, Germany, which is expected to officially come online this year. The company has also inked partnerships with textile collectors and sorters and spoken with more than 100 brands and retailers to drum up interest for its Reju Polyester product, according to CEO Patrik Frisk.

“We are talking to everybody in the American market, and everybody in the European market,” said Frisk, a former Under Armour chief executive with decades at brands including The North Face, Timberland and Gore-Tex.

The global popularity of polyester, brewed from the fossil fuels that have hastened the climate crisis, has skyrocketed in recent decades, featuring in two-thirds of new clothing. The world churns out 33 million metric tons of plastic-based fibers each year. Only 3 percent gets recycled, according to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation.

The waste is a mounting problem for the fashion brands and retailers that are gradually being forced to deal with their materials after end of use, thanks to extended producer responsibility (EPR) regulations in the European Union and California.

Competition

Numerous ventures are throwing fortunes and bold claims behind creating a circular economy for polyester that treats tossed-out textiles as a commodity rather than a liability.

One Reju competitor, Circ, based in Danville, Virginia, shared plans on May 19 to build a $500 million polyester recycling plant in France, backed by the French government and the European Union. Its recycled fibers have appeared in clothes by Zara, Patagonia, H&M and Levi’s.

Ambercycle and Worn Again Technologies also break down mixed textiles, such as the polyester-cotton blends ubiquitous to T-shirts, into raw material for new clothes.

A family affair

One thing that sets Reju apart: family connections. Its parent company, Technip Energies, has been in the polyester business for nearly 70 years. Its technology appears in 40 percent of the world’s 370 steam crackers, the industrial plants cranking out ethylene, a building block of polyester. TEN Zimmer, which Technip bought in 2015, processes polyester and nylon, another recycling frontier for fashion. One thousand polyester plants around the world use its technology.

Technip Energies, which today has a 17,000-person workforce, was formed in 2021 by the merger of TechnipFMC and FMC Technologies. Its origins reflect the evolution of the oil and gas industry. In 1958, Technip took shape as the French Petroleum Institute, or IFP, in Paris. FMC Technologies originated in 1883 as an insecticide maker.

Reju, founded in 2023 and employing 75 workers so far, is part of Technip Energies’ attempts to transition to a lower-carbon future. Those attempts also include investments in blue hydrogen, carbon capture and storage and recycled and biobased chemicals.

Technip Energies’ 2021 sustainability report set net zero deadlines of 2030 for Scopes 1 and 2, and of 2050 for Scope 3. It is not working on those emissions goals with the Science Based Targets initiative (SBTi), however, which in 2022 put on hold its consideration of oil and gas companies.

In 2024, Technip Energies grew revenues by 14 percent, to 6.9 billion euros.

Regional hubs

Not surprisingly, Reju is targeting population centers rife with unwanted, post-consumer clothes.

In the United States, it is finalizing the details of a new plant while collaborating with Goodwill and Waste Management on a garment recycling pilot. In April, Waste Management launched a textile curbside collection service in Troutdale, Oregon, which will be replicated in other cities. Goodwill sorts the apparel and will provide what it can’t sell to Reju.

“Reju has built a credible network of feedstock suppliers, which is often a bigger problem to solve than the chemistry,” said Marcian Lee, an analyst with Lux Research, “so I think it has a good shot at success.”

The polyester trap

Love it or hate it, polyester is functional, durable and cheap. “You have a really good product, a highly efficient system, that’s one of the largest commodities in the world,” Frisk said. It will take a generation to scale a potential replacement. Until then, Frisk said, “we can either continue to put it into the ground or we can burn it.”

Unless of course, we recycle it. Reju breaks down polyester molecules into a monomer, before building it back up again. It uses IBM’s VolCat technology, co-developed with Under Armour while Frisk was its CEO. In 2019, IBM shared with Trellis that, just as VolCat — short for volatile catalyst — could handle polyester bottles coated with milk or other gunk, it can manage the dyes and pigments on polyester clothing.

By returning “to the origin of polyester,” Frisk said, Reju can design lower-shedding synthetic fibers, yarns and fabrics that harm nature less and will be easier to manage at end of use.

No matter the efficiency and scalability of their recycling approaches, Reju and its rivals enter an industry being built from scratch.

“We actually spend less time than you might think on the technology itself, and much more on building out the system, from both a feedstock perspective and the downstream perspective of getting it to actually work as a circular system,” Frisk said.

Reju’s intended new site, at the 1,9000-acre Chemelot Industrial Park, is tucked into the southern tip of the Netherlands, between Belgium and Germany. Technip Energies’ board will make the final investment decision, which is expected to fall between $200 million and $300 million.

Laying down the pipes

“The textile industry is essentially catching a free ride on infrastructure that’s been built for other stuff,” Frisk said. “The oil pipes and the refineries and the cracking plants, all of that has been built for different things and we’re only a small part of it at the end,” he said.

“Our post-consumer textile waste stream has to be as robust as the oil pipeline that comes out of the oil ship and goes into a refinery, then ultimately into the polyester plant,” Frisk said. “So that has been the first priority, because if you don’t build that, you will not have anything to sell to the brands or the retailers.”

The next challenge will be convincing brands to pay more for the recycled alternative. “Until we have cost parity the use of recycled fibers is going to remain negligible, even with ties to a heavy polyester use brand,” said Liz Alessi, an apparel sustainability consultant in New York City.

The post French startup aims to recycle 300 million pieces of polyester clothing a year appeared first on Trellis.

.jpg)