Flamingos conjure ‘water tornadoes’ to trap their prey

The brightly colored birds are pretty adept predators. The post Flamingos conjure ‘water tornadoes’ to trap their prey appeared first on Popular Science.

A pink flamingo is typically associated with a laid back lifestyle, but the way that these leggy birds with big personalities feed is anything but chill. When they dip their curved necks into the water, the birds use their feet, heads, and beaks to create swirling water tornadoes to efficiently group their prey together and slurp up them up. The findings are detailed in a study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

“Flamingos are actually predators, they are actively looking for animals that are moving in the water, and the problem they face is how to concentrate these animals, to pull them together and feed,” Victor Ortega Jiménez, a study co-author and biologist specializing in biomechanics at the University of California, Berkeley, said in a statement. “Think of spiders, which produce webs to trap insects. Flamingos are using vortices to trap animals, like brine shrimp.”

In the study, the team from UC Berkley, Georgia Tech, Kennesaw State University in Marietta, Georgia and the Nashville Zoo looked at a group of Chilean flamingos (Phoenicopterus chilensis) in the Nashville Zoo and 3D printed models of their feet and L-shaped bills.

“Flamingos are super-specialized animals for filter feeding,” Ortega Jiménez said. “It’s not just the head, but the neck, their legs, their feet and all the behaviors they use just to effectively capture these tiny and agile organisms.”

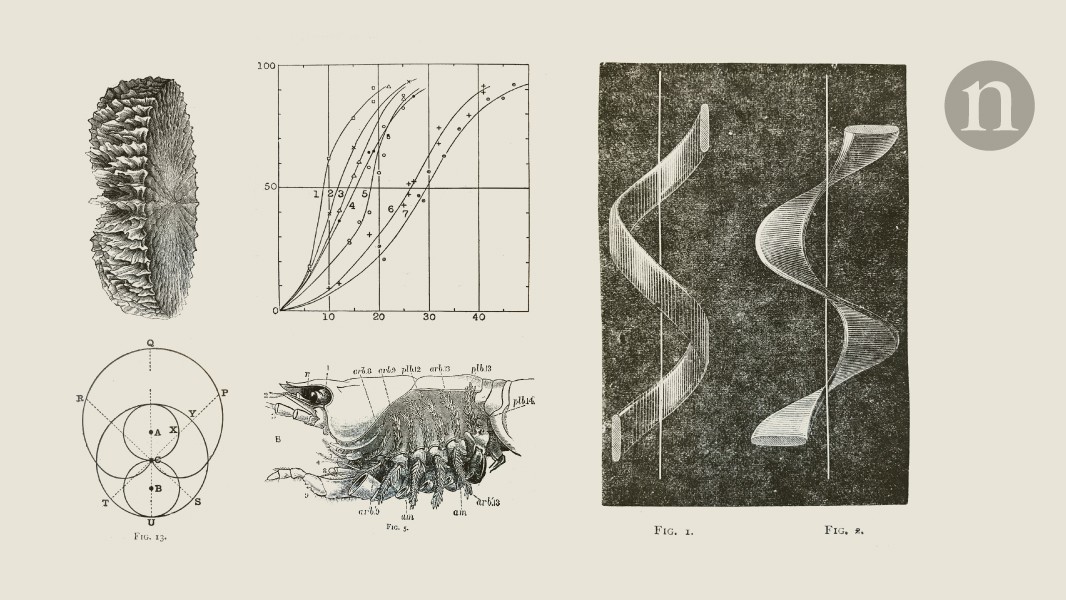

Flamingo feet are webbed, but like many wading birds, they are also floppy. When feeding, the birds use their feet to churn up the sediment at the bottom of shallow water. The flamingos then propel the sediment forward with little whorls that they draw up to the surface by jerking their heads upwards like a plungers–creaing these mini water tornadoes. The whole time, the birds’ heads stay upside down within the watery vortex, with their angled beaks moving to create smaller vortices that bring the sediment and food up into their mouths. Inside the mouth, the sediment is strained out.

[ Related: Why flamingo milk is pink. ]

Among birds, flamingo beaks are unique. They are flattened on the angled front end, so that when the head is upside down in the water, the flat portion is still parallel to the bottom. This helps flamingos deploy another technique called skimming. They use their long S-shaped neck to push its head forward while rapidly clapping its beak. The motion creates sheet-like vortices that trap prey. The tiny tornados were strong enough to trap typically agile brine shrimp and microscopic crustaceans called copepods.

“It seems like they are filtering just passive particles, but no, these animals are actually taking animals that are moving,” Ortega Jiménez said.

When the team created a 3D model of the L-shaped beak, they found that pulling the head straight upward in the water creates a vortex. This vortex swirling around a vertical axis concentrates food particles at a speed of up to 1.3 feet per second.

The fluid principles the team discovered in flamingos could have some engineering applications in the future. It could help engineers develop better systems for concentrating and sucking up tiny particles from water, potentially the ultra prolific microplastics. They could also be applied to better self-cleaning filters or robots that can walk and run in mud the way flamingos can.

The post Flamingos conjure ‘water tornadoes’ to trap their prey appeared first on Popular Science.

![The breaking news round-up: Decagear launches today, Pimax announces new headsets, and more! [APRIL FOOL’S]](https://i0.wp.com/skarredghost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lawk_glasses_handson.jpg?fit=1366%2C1025&ssl=1)