Cannibal tadpoles help Australia fight invasive species

Researchers have created genetically engineered 'Peter Pan' cane toads. The post Cannibal tadpoles help Australia fight invasive species appeared first on Popular Science.

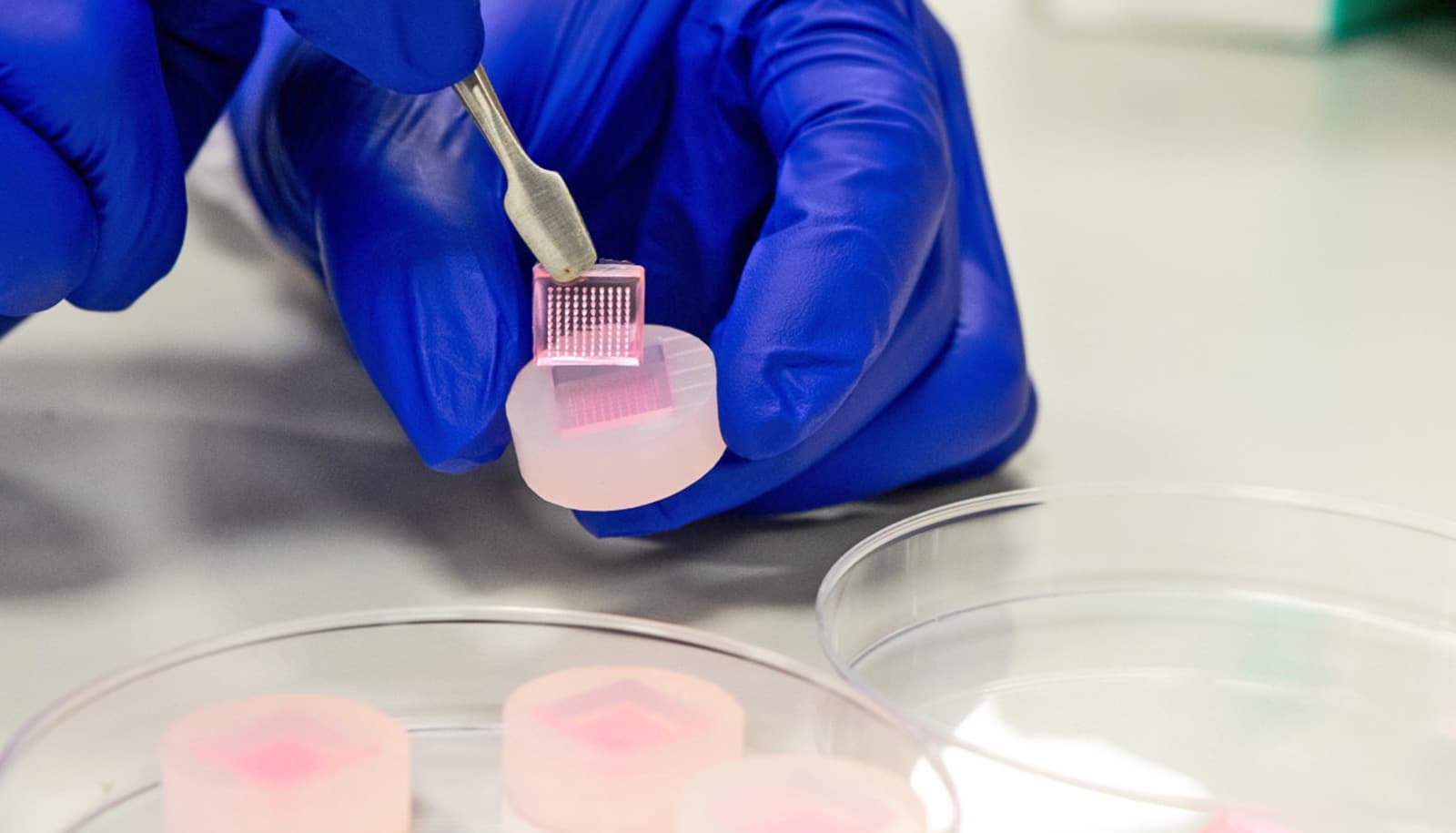

Genetically modified, cannibal tadpoles may be the solution to Australia’s nearly century-old invasive cane toad problem. According to researchers, removing a single gene that controls production of a hormone called thyroxine can create swarms of tadpoles incapable of their usual metamorphosis into adult amphibians. Cane toad tadpoles have ravenous appetites already, so prolonging this life stage allows the modified hatchlings to devour as many as three times the toad eggs than normal.

“We seem to have ended up with these sort of quite large, relatively long-lived voracious cannibals that are just ideally suited to control the numbers of their own species,” Rick Shine, an evolutionary biologist and ecologist at Australia’s Macquarie University, explained to Australia’s ABC News.

It’s been about 90 years since Australia introduced tropical cane toads (Rhinella marina) onto Queensland farms. Around 2,400 toads were released into the wild in 1935 in an attempt to rein in agricultural pests. But instead of controlling destructive sugar cane beetle populations, the amphibians quickly became their own ecological catastrophe. With no major predators and a devastating effect on native reptile species, the cane toad turned into a case study for invasive species. Today, an estimated 200 million cane toads are hopping across northern Australia with no signs of slowing down.

Female cane toads lay upwards of 30,000 eggs per clutch twice a year. Researchers theorize that genetically modifiying even a fraction of those clutches could significantly curb overall numbers.

Unfortunately, Shine’s team still faces a bit of a conundrum: If their Peter Pan tadpoles never grow up, then they aren’t able to reproduce more cannibalistic offspring. The team’s current process requires manually injecting individual frog eggs with a solution that neutralizes the thyroxine hormone, which isn’t possible to scale.

Shine and colleagues are already working on some potential solutions. One option may involve adding thyroxine into a body of water after releasing the genetically modified tadpoles, thereby allowing some of them to grow into adulthood. Those cane toads would in turn eventually produce their own Peter Pan hatchlings, allowing researchers to repeat the cycle.

“If we could raise those young toads to adult size and breed them, then we would have 20,000 or 30,000 Peter Pan tadpoles per clutch,” Shine explained. “It wouldn’t really take very many adult toads with that genetic change for us to have a vast supply of the sorts of tadpoles we’d like.”

Work still needs to be done to produce healthy adult Peter Pan toads, but Shine’s team believes further research will produce the desired effects. Meanwhile, the project will require rigorous evaluation by Australian regulatory authorities before trials can begin in the wild.

The post Cannibal tadpoles help Australia fight invasive species appeared first on Popular Science.

![The breaking news round-up: Decagear launches today, Pimax announces new headsets, and more! [APRIL FOOL’S]](https://i0.wp.com/skarredghost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lawk_glasses_handson.jpg?fit=1366%2C1025&ssl=1)