Are we in a sixth mass extinction?

We’re in a biodiversity crisis, but it's tough to compare it to past periods of mass death. The post Are we in a sixth mass extinction? appeared first on Popular Science.

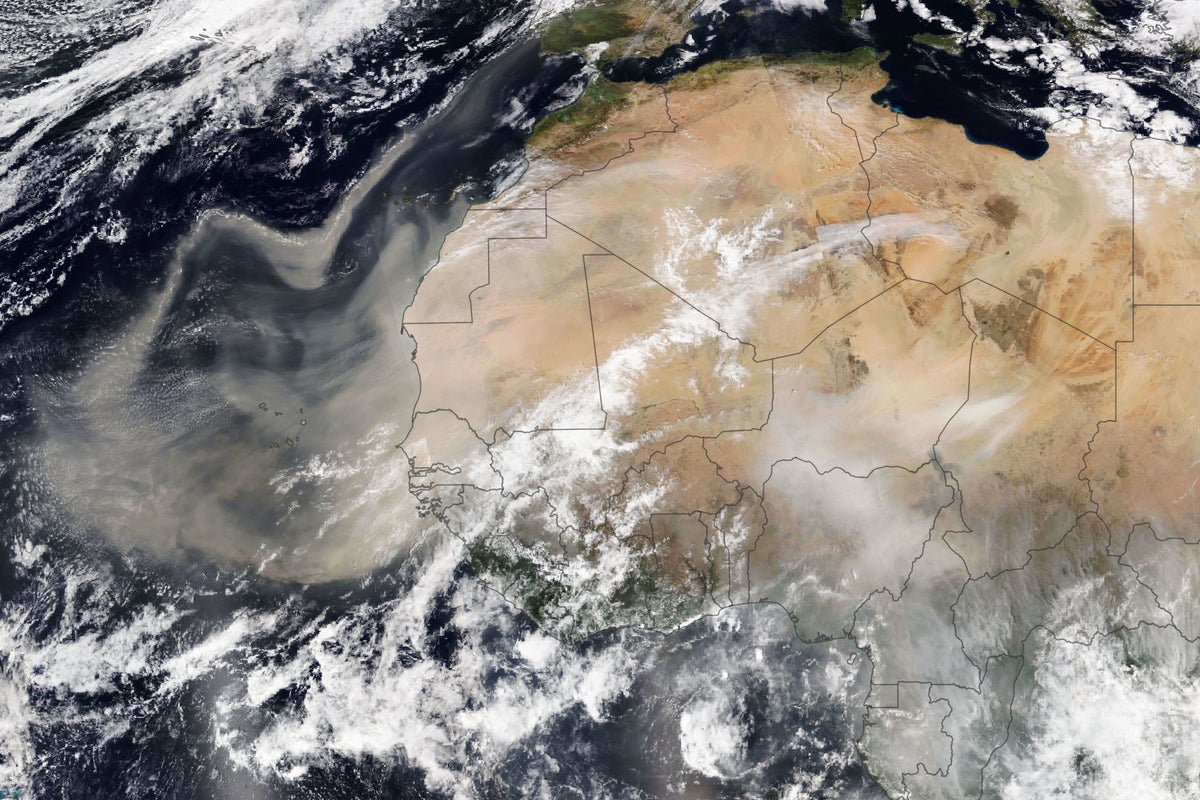

Around 66 million years ago, a six-mile-wide asteroid hit Earth, triggering the extinction of three-quarters of all living species. The age of dinosaurs, which had lasted 165 million years, ended with a fiery crash and suddenly sooty skies.

Farther back in our planet’s history, volcanic eruptions, rapid climate change, and plummeting oxygen levels have caused at least four additional mass extinctions, with smaller pulses of biodiversity loss also showing up in the fossil record. In each of the five largest events, which spanned anywhere from thousands to tens of millions of years, at least 75 percent of Earth’s species died out. These are the most commonly agreed upon major mass extinctions in paleontology.

You’ve also likely heard about a sixth one. Many ecologists and biologists say we’re on the precipice (or already in the midst) of another era of mass extinction. This sixth mass extinction, also referred to as the Holocene or Anthropocene extinction, is described as ongoing and caused by human activities. Hunting, overfishing, habitat destruction, human encroachment, and invasive species introductions are the major drivers of the losses incurred thus far. Human-caused climate change is also set to become another factor, as decades of rising temperatures, shifting precipitation patterns, and increasingly extreme weather catch up to already stressed ecosystems.

It’s indisputable that humans shape life on Earth in major ways, and that animals and plants are dying out at an alarming rate. But is it true that our impact is on par with that of an asteroid? Not all scientists agree.

A biosphere in crisis

There is no question that Earth is losing species fast. “Biodiversity crisis is a pretty accurate term” to describe the present moment, says John Wiens, an evolutionary ecologist at the University of Arizona. “Extinction crisis” is another, he adds, “based on the large number of species that are threatened with extinction.”

Five other experts that Popular Science corresponded with for this article all agree on this ‘crisis’ terminology. In comparison with background levels of extinction, all of our sources said that current extinction rates are much higher.

Extinction isn’t always a sign of disaster. It’s also a natural outcome of evolution. As species diverge, compete, and struggle to survive, not all of them make it long-term. Conditions on Earth shift over geologic time, and those forces inevitably lead to some dead ends on the tree of life.

[ Related: Earth’s 5 catastrophic mass extinctions, explained. ]

However, throughout most of our planet’s history, the rate of new species emerging has exceeded the rate of species dying out, says Gerardo Ceballos, an ecologist and conservation biologist at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Thus, biodiversity normally exists in a positive balance.

Currently, we’re losing species far faster than new ones emerge. Present extinction rates are up to 100 times faster than background levels, according to one 2015 study co-authored by Ceballos. In that analysis, Ceballos and his colleagues estimated the natural vertebrate extinction rate sits at around two species lost per 10,000 species each century. Then, they compared that statistic with the number of confirmed and likely extinctions recorded on the International Union of Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List. They determined that, even using conservative numbers, the extinction rate for every vertebrate group was between eight and 100 times the background rate. The species losses incurred in the past 100 years would have taken thousands of years to occur naturally, per the assessment.

Other counts find the current rate of extinction is even higher. One often cited 2014 study concluded Earth is losing species 1,000 times faster than natural background rates. That analysis also reported the level of loss is poised to accelerate to 10,000 times the background rate in the near future.

These numbers vary widely in large part because the estimates of background extinction rates are difficult to pin down. The fossil record is incomplete, so scientists generally rely on mathematical models and reconstructions of the past to determine what was once alive and when it died out. Small shifts in starting assumptions can lead to major changes in the final calculations. The time period you’re calculating average extinction rate over and types of organisms you’re assessing also impact the result. This same ambiguity in estimating extinction rate persists in the present.

Extinction is tough to track

Though Wiens describes our moment as a biodiversity crisis, he doesn’t believe it meets the bar for a sixth mass extinction. “No one has provided a quantitative analysis that has really shown that,” he says.

If the top five major mass extinctions in the paleontological record each killed off at least 75 percent of species at the time, then the sixth one should theoretically cross the same threshold. Yet so far, the IUCN has confirmed fewer than 1,000 extinctions from the past 500 years–just about 0.1 percent of all known species, according to an analysis co-authored by Wiens in April.

We have not catalogued every living species, and the IUCN is far from having assessed all known species. The IUCN database is also biased, skewing towards large, charismatic vertebrates and wealthy regions like North America. The criteria for extinction are strict, requiring extensive surveys, and yet sometimes species reappear after being declared gone forever. Still, the IUCN dataset is among the best windows we have into the state of life on Earth, and it suggests there’s a way to go before three quarters of species are gone.

[ Related: Earth’s ‘Great Dying’ killed 80-90% of life. How some amphibians survived. ]

However, it’s worth noting that other assessments estimate a much higher proportion of species have already disappeared. One 2022 paper, which extrapolated extinction rates from data on mollusks, found that upwards of 10 percent of all species may have gone extinct in the past 500 years.

And, those like Ceballos who argue a major mass extinction has already begun, point to calculations that indicate we could reach that grim, 75 percent mile marker in just a few centuries. If all IUCN threatened species went extinct in the next 100 years, and that rate of species loss continued, Earth would surpass 75 percent loss of species across most vertebrate animal groups in under 550 years, according to a landmark 2011 review paper. This study published in Nature, remains among the most thorough quantitative assessments of extinction trends.

Yet to write every threatened species off as doomed to imminent extinction would be a mistake, says Stuart Pimm, a conservation biologist at Duke University and president of the conservation non-profit, Saving Nature.

“We have no idea what the future is,” he says. And, in the meantime, “there’s a lot of things we can do.” Pimm points to conservation success stories like the rebound of certain baleen whale populations and the stabilization of savanna elephant numbers over the past 25 years. He worries that claims about the sixth extinction might leave the public resigned to what might otherwise be a preventable catastrophe.

“It’s not inevitable,” Pimm says.

We can’t predict the future (but it doesn’t look great)

From the paleontological perspective, mass extinctions are something that can only be definitively confirmed in the past tense. They are defined based on the proportion of species that existed before, but not after a cataclysmic event like a major asteroid strike. If there’s not yet an after, it’s impossible to say for sure what number of lineages died out. There are no crystal balls in science. And in that uncertainty, there’s room for hope that we could stop species from sliding off the cliff.

But nearly half of all animals are losing population worldwide, according to a 2023 estimate, based on trend data for more than 71,000 species. Barring exceptional levels of investment and intervention, lots of species are already doomed to extinction, says Sarah Otto, an evolutionary biologist at the University of British Columbia. “Many of the extinctions we think that humans are causing haven’t actually happened yet. These are the ‘living dead’ species whose population sizes are small, whose habitats are fragmented,” she explains. “There’s a lot of extinction debt.”

[ Related: An ‘ancestral bottleneck’ took out nearly 99 percent of the human population 800,000 years ago. ]

A 2020 report from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) found that an average of 25 percent of species across animal and plant groups are threatened with extinction within decades, and that the human impacts to blame are intensifying. Without preventative action, as species disappear, “there will be a further acceleration in the global rate of species extinction,” the report authors write.

Species depend on one another for survival, Otto notes. For example, in our acidifying and warming oceans, coral reefs are teetering on the brink. If they go, then the fate of the many species dependent on the infrastructure they provide is unclear. Major losses of marine life could then have knock-on effects on land.

Notably, the IPBES report doesn’t directly consider the influence of climate change on future extinction rate. If it did, “those projected numbers could really go up,” says Otto.

Even under Wiens’ comparatively rosy outlook, he still expects 12 to 40 percent species losses over the next century. And if species don’t disappear across their entire ranges, local losses and population declines can still have major repercussions for ecosystem function and human society.

The 75 percent threshold is an arbitrary line, Otto notes. Lots can go wrong before we officially place sixth in the world’s worst contest. Human impacts on biodiversity “will be seen in the fossil record,” she says. “Whether or not it’s going to be up there in the top six is really a matter of what we do next.”

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.

The post Are we in a sixth mass extinction? appeared first on Popular Science.