An inside look at a fungi-forward, faux-leather material maker

Trellis snagged a Hydefy factory tour, learning how the well-funded Chicago start-up brews livestock-free material it hopes will disrupt the fashion world. The post An inside look at a fungi-forward, faux-leather material maker appeared first on Trellis.

Animal, vegetable or mineral. Most materials derive from one of those categories of nature. But a Chicago startup is cultivating a new class of materials from the fungus kingdom.

Hydefy, in fact, is developing alternatives both leather and fossil fuel-based plastics.

The company just emerged from stealth mode after spending five years quietly formulating its vegan “leather.” In March, it took the wraps off its first branded product, a $1,500 silvery purse by Stella McCartney.

“Our vision is that we will introduce a new option for consumers that they can feel good about,” said Hydefy General Manager Rachel Lee.

Among dozens of startups playing with mycelium, found in the roots of mushrooms, Hydefy has evaded the spotlight. That’s even as its sister startup, Nature’s Fynd, raked in more than $500 million of investments, including from Bill Gates’ Breakthrough Energy Ventures. Nature’s Fynd formulates fungus-based, protein-rich “yogurt” and breakfast patties that sell at Whole Foods and Mariano’s markets.

The sibling companies share a nearly 50,000 square-foot R&D and production plant in Chicago’s former Union Stock Yards. The irony of being situated in America’s former meatpacking “jungle” is not lost on Lee, who is also a senior director at Nature’s Fynd.

“We started with cream cheese and breakfast patties in 2021, on Valentine’s Day, as our love letter to Earth,” she said. “We were replacing the inside of a cow. Now we can say we’re replacing all the parts.”

The quest to bring climate-friendly fungi to the industrial production of fashion and food sprang from NASA research into “extremophile” organisms that could survive in alien conditions. The fungus has traveled to the International Space Station to test its potential for feeding astronauts. Fynder Group, the umbrella company, emerged from research by Mark Kozubal, who in 2009 noticed fungi sprouting from algae sampled from a hot spring at Yellowstone National Park. The Latin name for the fungus strain, by the way, is Fusarium strain flavolapis (flavo means yellow and lapis means stone).

The company was founded in a Bozeman, Montana, garage but eventually relocated to the Windy City.

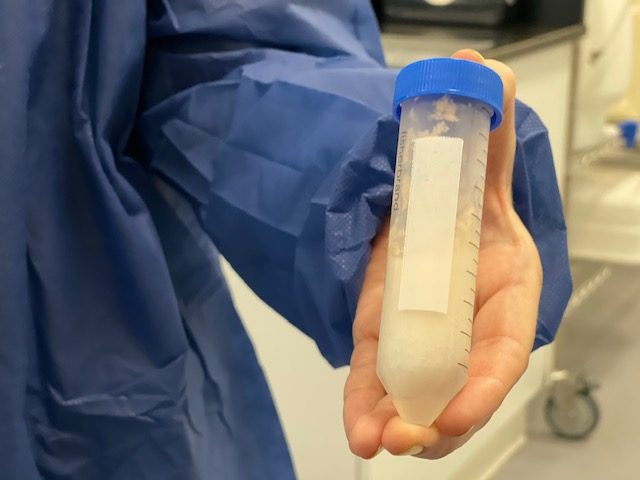

Hydefy recently invited Trellis to tour its Chicago plant, where it and Nature’s Fynd draw their fungi from the same cooler. The organism is rare — it may not even grow beyond its geothermal origin point in Yellowstone — so backup copies are kept alive in undisclosed locations.

From cold storage the microorganisms’ paths diverge, either to a Nature’s Fynd lab-like kitchen or a Hydefy fabrication room. (Sometimes Hydefy recycles scrap fungi from Nature’s Fynd.)

Whatever works

Hydefy takes an “all of the above” approach to fermentation technology. With liquid air surface fermentation, the fungi forms a mat as it grows, Kombucha-like, in trays. Another method is submerged fermentation. In equipment typically found in breweries, fungi grow vertically inside large metal tanks.

“This process allows us to re-fit existing equipment and grow our network, whether national or global,” Lee said.

The living output, called Fy, comes out wet. Once washed, diced and dried, it resembles potato chips, but with an earthy aroma.

The company crushes those chips into powder, mixing in sugarcane polymers. It forms that powder into pellets, which are fed into an extruder, at which point heat and pressure are added to churn out sheets that are similar in size to fabric rolls.

The machines, which generally produce vinyl flooring and mats, have been customized by Hydefy engineers. (Early on, the company experimented with a panini press.)

There’s a light burning smell as staff tinkers with the equipment. They swap out attachments to produce different sizes and composites of the material.

The base material comes out a buttery yellow. The company can add colors.

At a nearby table, team members add texture to the rolls, a process similar to embossing. A finishing layer includes silicone and a bio-based polyurethane from either corn or sugarcane. Hydefy has about 50 different finishing formulations. Notably, when an attache case brought to a trade show in London became unpackaged during shipping, the wear and tear resembled the scuffing typical of animal leather.

The material can have various hand feels, including pebbled leather, crushed velvet and suede effect. In addition, the company can produce non-leather textures that have, say, a metallic sheen or other patterns, such as the topography of Yellowstone Park. Some of the material smells nearly like leather, although whether Hydefy should mimic that aroma is a point of discussion. So too a perfumed purse: A Nature’s Fynd team member helped give Fy a rose scent.

“Some of our favorite inventions have come from controversial, love-or-hate decisions,” Lee said.

A diversified team

Hydefy employees come from a swath of backgrounds. They include a scientist who used to make fighter jets, a former banker and a fermentation scientist. The team also includes Senior R&D Director Jeremy Gantz, who spent more than seven years in materials innovation at Nike. He is one reason that Hydefy is comfortable eyeing the footwear market. At least three staffers are wearing test shoes made from Fy.

“As an industry, we’re not going to find people who used to work in this because it’s a new category,” Lee said. “That’s why it was more important to look for scientists who have the material science background, or who have the chemistry background, or even who have textile background.”

The post An inside look at a fungi-forward, faux-leather material maker appeared first on Trellis.