‘They have no one to follow’: how migrating birds use quantum mechanics to navigate

Evidence is mounting to explain how birds use the Earth’s magnetic field to help fly thousands of miles with unerring accuracy – a discovery that may help advance quantum technologyTo the seasoned ear, the trilling of chiffchaffs and wheatears is as sure a sign of spring as the first defiant crocuses. By March, these birds have started to return from their winter breaks, navigating their way home to breeding grounds thousands of kilometres away – some species returning to home territory with centimetre precision. Although the idea of migration often conjures up striking visions of vast flocks of geese and murmurations of starlings, “the majority,” says Miriam Liedvogel, director of the Institute of Avian Research (IAR) in Germany, “migrate at night and by themselves, so they have no one to follow.”Liedvogel has had a fascination with birds since childhood, and often wondered how they navigate these lengthy migrations. She is not alone, with even Aristotle pondering the mystery and mistakenly concluding that redstarts change into robins over the winter. As Liedvogel points out, migration behaviour is varied and much remains unknown, but we now have enough data on bird behaviour to rule out species transmogrification, among other theories. Studies have revealed that 95% of migrating birds travel at night, alone, and without parental guidance, so the behaviour must be partly inherited. These birds use the Earth’s magnetic field to find their way, and it is likely that at least part of the biological mechanism that allows them to do this can be explained through quantum mechanics. Continue reading...

Evidence is mounting to explain how birds use the Earth’s magnetic field to help fly thousands of miles with unerring accuracy – a discovery that may help advance quantum technology

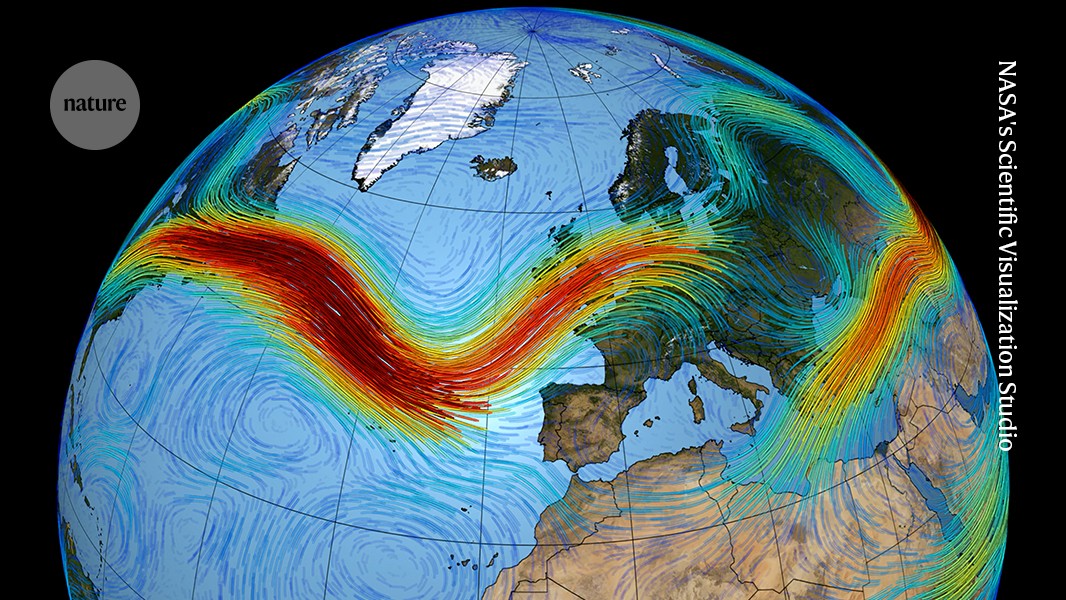

To the seasoned ear, the trilling of chiffchaffs and wheatears is as sure a sign of spring as the first defiant crocuses. By March, these birds have started to return from their winter breaks, navigating their way home to breeding grounds thousands of kilometres away – some species returning to home territory with centimetre precision. Although the idea of migration often conjures up striking visions of vast flocks of geese and murmurations of starlings, “the majority,” says Miriam Liedvogel, director of the Institute of Avian Research (IAR) in Germany, “migrate at night and by themselves, so they have no one to follow.”

Liedvogel has had a fascination with birds since childhood, and often wondered how they navigate these lengthy migrations. She is not alone, with even Aristotle pondering the mystery and mistakenly concluding that redstarts change into robins over the winter. As Liedvogel points out, migration behaviour is varied and much remains unknown, but we now have enough data on bird behaviour to rule out species transmogrification, among other theories. Studies have revealed that 95% of migrating birds travel at night, alone, and without parental guidance, so the behaviour must be partly inherited. These birds use the Earth’s magnetic field to find their way, and it is likely that at least part of the biological mechanism that allows them to do this can be explained through quantum mechanics. Continue reading...