The evolution of sunglasses from science to style (and back again)

The technology behind shades has changed over the centuries. The post The evolution of sunglasses from science to style (and back again) appeared first on Popular Science.

You throw them in your bag or keep them in your car. You buy them in bulk because they’re incredibly losable. You drive with them, walk with them, and play sports with them. And, of course, you’ve never thought about their origin story: Why would you? They’re just an old, beat-up pair of aviators, classic Ray-Bans, or maybe a glamorous cat eye. They’re your sunglasses.

But this everyday, ubiquitous piece of tech has a long history. It’s taken centuries for this humble accessory to morph from Inuit snow goggles to medieval Chinese quartz lenses to 18th-century tinted glasses to today’s sunnies. Innovations like UV protection and polarization helped drive their popularity, especially in the 20th century, as sunglasses became an essential tool for pilots, athletes, and anyone working outdoors. Hollywood elites also embraced shades, cementing them as the ultimate accouterment of effortless cool.

Design historian Vanessa Brown, a senior lecturer at Nottingham Trent University and author of Cool Shades: The History and Meaning of Sunglasses, says it’s difficult to point to the origin of sunglasses without first defining what sunglasses are. Are they “something that you put in front of your eyes to shield you from the sun?” Or are they “something made of glass, something that stays on you, and something which is only designed to shield your eyes from the sun as opposed to [enhancing] problematic vision”?

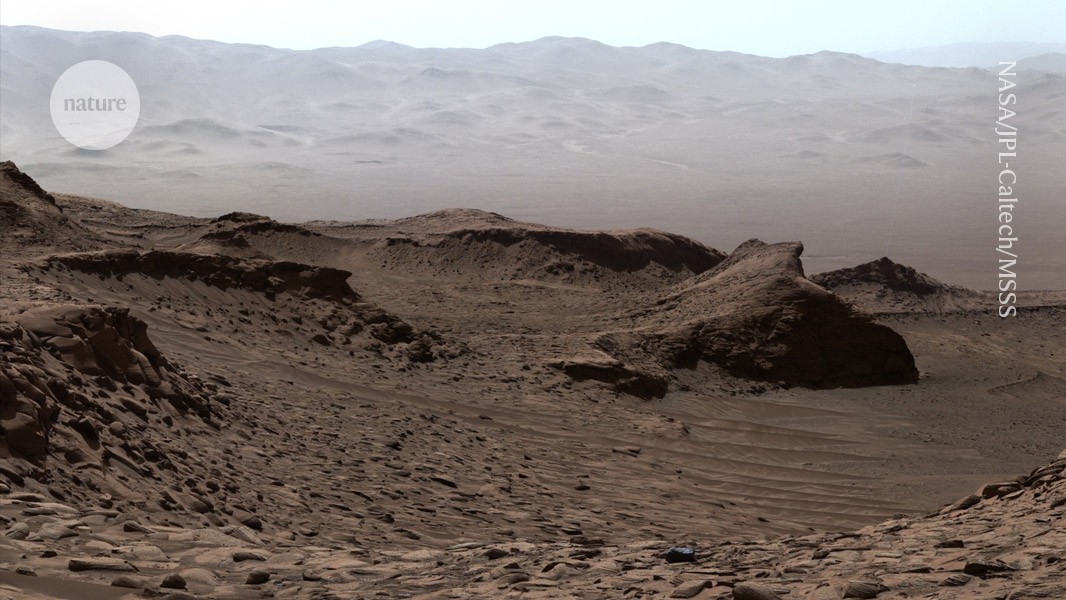

The earliest known eyewear designed to protect against the sun likely originated in the ancient Arctic. For thousands of years, Inuit and Yupik people wore goggles made of bone, driftwood, and walrus ivory with tiny eye slits to prevent snow blindness.

Julian Idrobo/Wikimedia, CC BY-SA 2.0

Another early example of sunglasses can be traced to 12th-century China, where medieval judges wore smoky quartz lenses to conceal facial expressions during hearings. These mineral lenses were also used as vision aids, beginning a long history of tinted lenses being used to improve visual perception. [

“The early history of sunglasses comes out of the history of corrective lenses,” says Jessica Glasscock, a fashion historian at Parsons School of Design and author of Making a Spectacle: A Fashionable History of Glasses.

Some of the earliest European corrective lenses can be traced to 13th-century Venice, Italy — Europe’s glass-making capital. “The first spectacles generally had tinted glass in them,” says Brown. “People often think that they’re sunglasses, but actually they’re corrective glasses.”

It wasn’t until around 1750 that tinted eyewear specifically designed to block the sun was created. Developed in Venice, these green-tinted glass lenses were set in tortoiseshell frames and widely used by gondoliers. Playwright and librettist Carlo Goldoni famously wore them, and the glasses became known as Goldoni glasses.

What’s surprising about Goldoni glasses, says Brown, is that “they arrived at a style that was really so modern,” down to the still-ubiquitous tortoiseshell frames.

Around this time, interest in glasses began to soar, says Glasscock: They became “high-tech accessories in the 18th century.” There were eye preservers, glasses with blue-tinted lenses thought to relax the wearer. There was the polemoscope, or jealousy glass, that let 18th-century aristocrats spy on people beyond their eye line.

The industrial revolution spurred the development of other useful eyewear, such as railroad glasses. The metal-framed glass lenses came in shades of gray, green, blue, and amber, and helped protect eyes from wind, dust, and light.

By the early 20th century, sunglasses really started catching on. Early examples “were initially developed for driving, flying — these aggressive, hyper-masculine, industrial sports of the early 20th century,” says Glasscock. This association with sports and innovation helped distinguish sunglasses from corrective lenses, which had long been linked to visual impairment and, by extension, physical weakness. As Glasscock succinctly puts it, “You have to have good eyes to fly.” The connection between sunglasses and athleticism gave shades a new cultural cachet: Sunglasses started becoming cool.

The 20th century also saw several key innovations in sunglasses. In the early 1900s, Rodenstock, a German eyewear manufacturer, developed tinted lenses that shielded eyes from harmful UV light. A few decades later, in the 1930s, American inventor Edwin Land created polarized lenses, which helped reduce glare. Polarization quickly “became a selling point for the eyewear as it started to be mass-produced,” says Glasscock.

Over the next few decades, sunglasses were everywhere. By the late 1920s, sunglasses were already “being sold in large quantities,” says Brown. A decade later, a story published in a 1939 issue of Popular Science proclaimed that “a craze for gaily colored sunglasses swept the country last year and is booming again.” By 1948, The Optical Practitioner reported that most people owned a pair of sunglasses.

Part of the reason sunglasses took off so quickly was their association with flying and heroism. In the 1930s, the U.S. military developed specialized polarized sunglasses known as aviators. The now-iconic sunglass style was modeled off of early, teardrop-shaped pilot goggles. During “the interwar period, [aviators] were associated with just flying. But with World War II, they take on this heroic image,” says Glasscock. When they began hitting department store shelves, suddenly everyone could feel like a hero in their own aviators.

In the early 20th century, sunglasses also became a necessary accessory for Hollywood elites. Here were all these glamorous people who were “in the desert sun or under literal hot white [film] lights,” says Glasscock, and they could use sunglasses. As photos of film stars began to proliferate in movie fan magazines like Photoplay, everyday people took note of their shades and wanted a pair. Sunglasses became a way for everyday people to embody an easy Hollywood cool factor.

The allure of sunglasses hasn’t ebbed since, and today they remain a wardrobe staple. The fact that sunglasses have retained their “cool factor” through the decades “is not normal,” says Brown. It goes beyond the fact that they’re a useful tool. “It rains a lot, but umbrellas aren’t always cool,” jokes Brown.

In a world that so often demands us to be on display and prove our worth, sunglasses offer a rare escape—they invite us to step outside, soak up the sun, and just be. No explanation needed. Just by putting them on, we’re cool.

The post The evolution of sunglasses from science to style (and back again) appeared first on Popular Science.

![The breaking news round-up: Decagear launches today, Pimax announces new headsets, and more! [APRIL FOOL’S]](https://i0.wp.com/skarredghost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lawk_glasses_handson.jpg?fit=1366%2C1025&ssl=1)