Sea worm’s reproductive bits grow their own eyes before mating

The branching marine worm has one head, many butts, and a busy sex life. The post Sea worm’s reproductive bits grow their own eyes before mating appeared first on Popular Science.

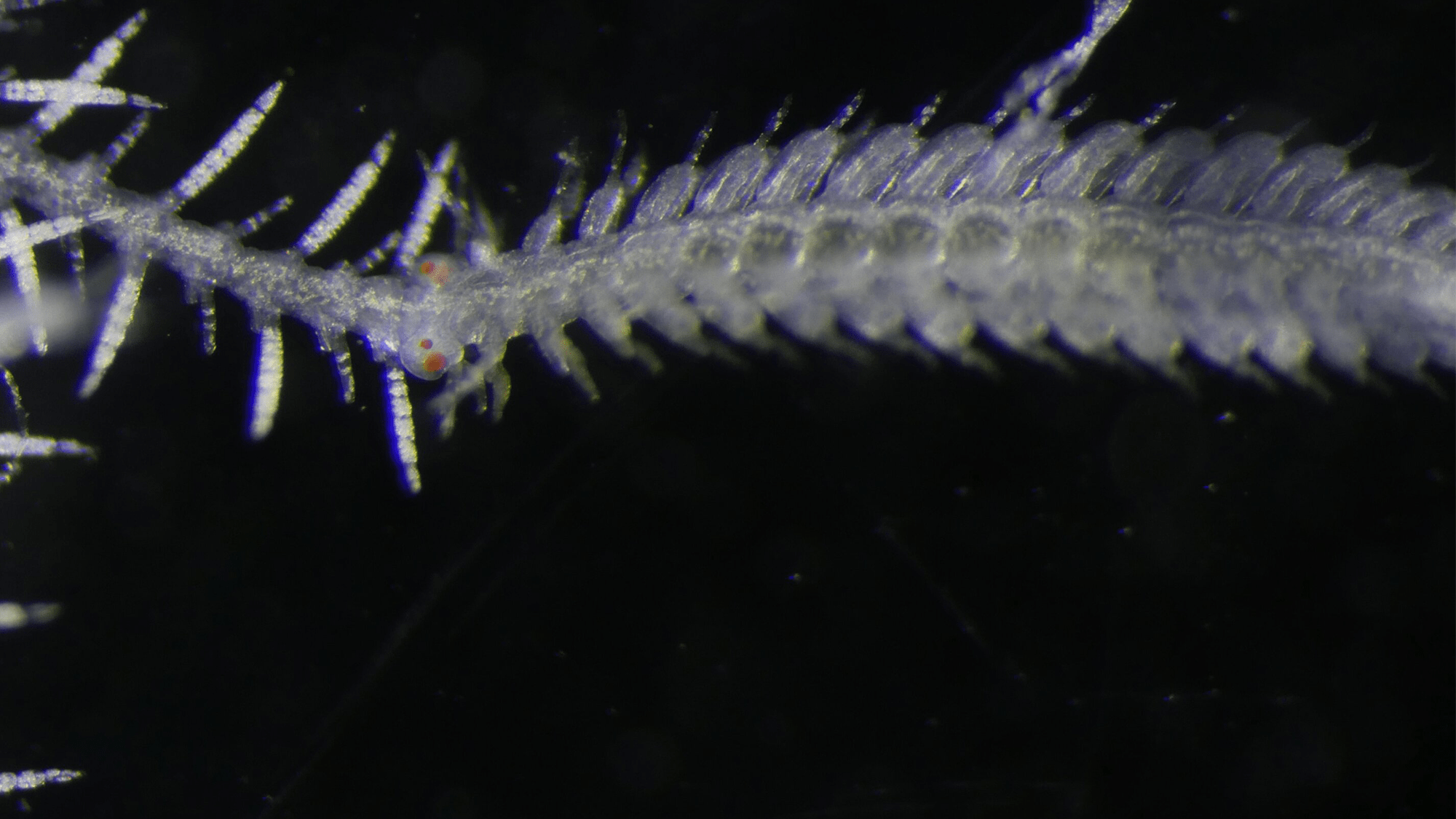

Even among the numerous gnarly animals swimming, crawling, and “flying” through the world’s oceans, the branching marine worm (Ramisyllis kingghidorahi) has a very interesting reproductive style.

Named after Godzilla’s three-headed nemesis, King Ghidorah, the worm lives inside of sea sponges in the Sea of Japan and reproduces by growing multiple body branches within the host sponge. Each of these tails can then produce separate living reproductive units called stolons—which can grow eyes. The stolons themselves do not live too long and break off from the branches to swim away to mate.

How this spindly animal can coordinate sexual reproduction with so many stolons across so many branches has puzzled scientists since its discovery in 2021 and 2022. We may have an answer though. The genes that control eye formation might be particularly active in Ramisyllis, which helps make more stolons, according to a study recently published in the journal BMC Genomics.

[ Related: Why these sea worms detach their butts to reproduce.]

In the new study, the team analyzed the gene expression across the different body regions on male, female, and juvenile specimens. This created a complete genetic activity map–or transcriptome.

With this genetic activity map in tow, the team saw some clear patterns. The differences in gene activity were more pronounced between the different body regions in the same worm than they were between the sexes. When comparing males with females, the stolons had the most distinctive genetic signatures. This likely reflects the stolons’ specialized role in gamete production and metamorphosis.

“We were surprised to find that the head of the worm, which was previously thought to house a sex-specific control system, didn’t show the dramatic differences we expected between males and females,” Guillermo Ponz-Segrelles, a study co-author and neuroscientist with the Autonomous University of Madrid, said in a statement. “Instead, the stolons emerged as the true hotspots of gene activity during sexual development.”

When looking into what’s behind the stolon eyes, the team found that there is upregulation of the genes related to eye development. Upregulation is the process by which genes are activated and produce more of the proteins corresponding with a certain gene’s function. This genetic upregulation could help Ramisyllis develop more of the eyes on their many stolons.

There could also be partial genome duplication in Ramisyllis, which may help explain why this worm has such a complex anatomy and reproductive system. Either way, it is equipped with a very unique genetic toolkit.

“This worm and its surreal, tree-like body made headlines around the world in 2021 and 2022, yet it continues to amaze us,” added Thilo Schulze, a study co-author and PhD candidate at Göttingen University in The Netherlands.” It challenges our understanding of how animal bodies can be organized, and how such strange forms of reproduction are orchestrated at the molecular level.”

Since numerous parts of branching worms’ reproductive biology remain a mystery, the team hopes the genetic tree from this study will help show how life evolves in some of the ocean’s hidden spots.

The post Sea worm’s reproductive bits grow their own eyes before mating appeared first on Popular Science.