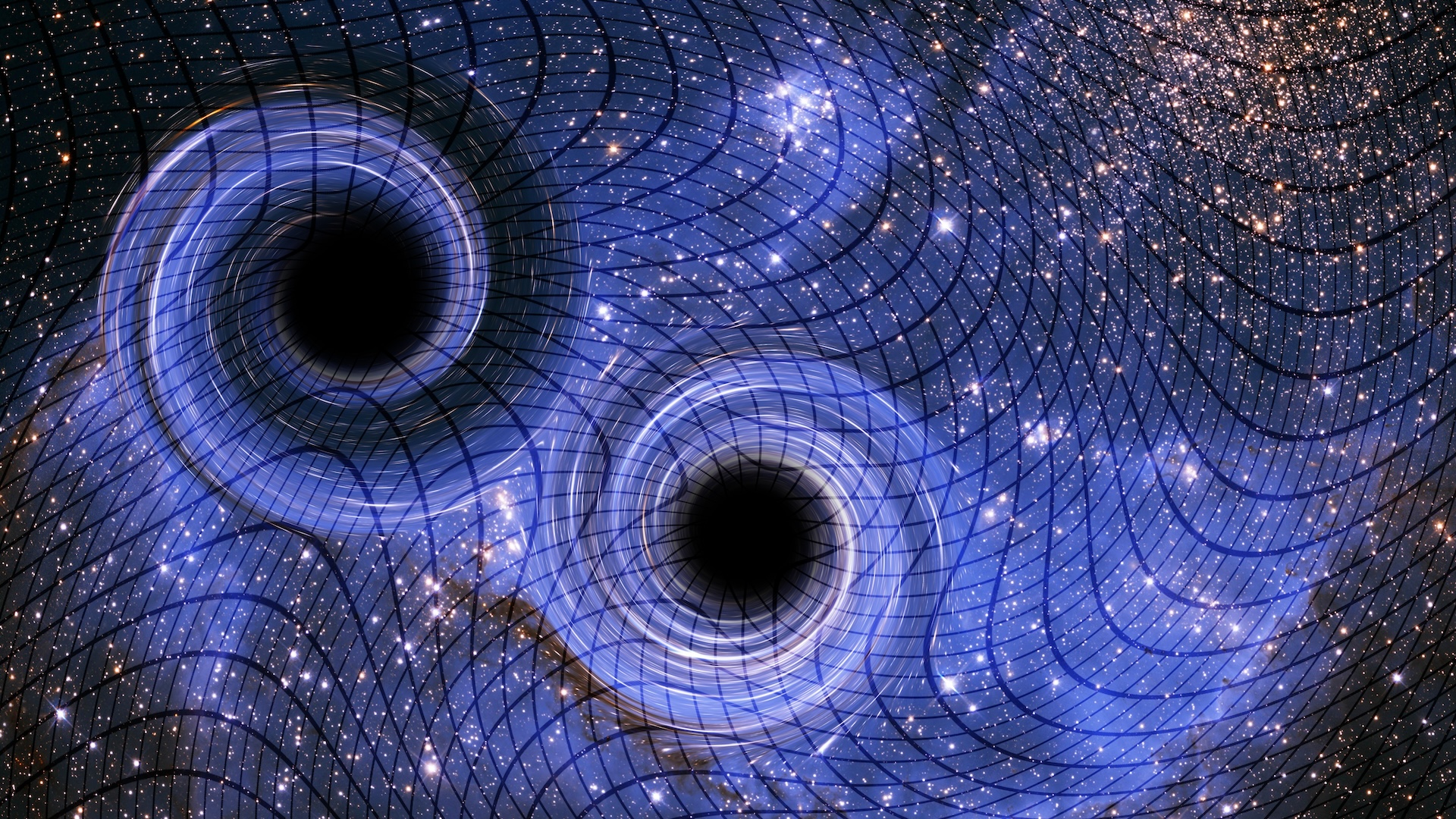

New evidence for water lurking under the moon’s poles

Chandrayaan-3’s lunar surface temperature data hints at some unexpected H20. The post New evidence for water lurking under the moon’s poles appeared first on Popular Science.

We tend to think of the moon as a cold, dusty rock, but in fact, its surface can get pretty hot during a lunar day. How hot? It turns out that the answer can vary dramatically over a very short distance.

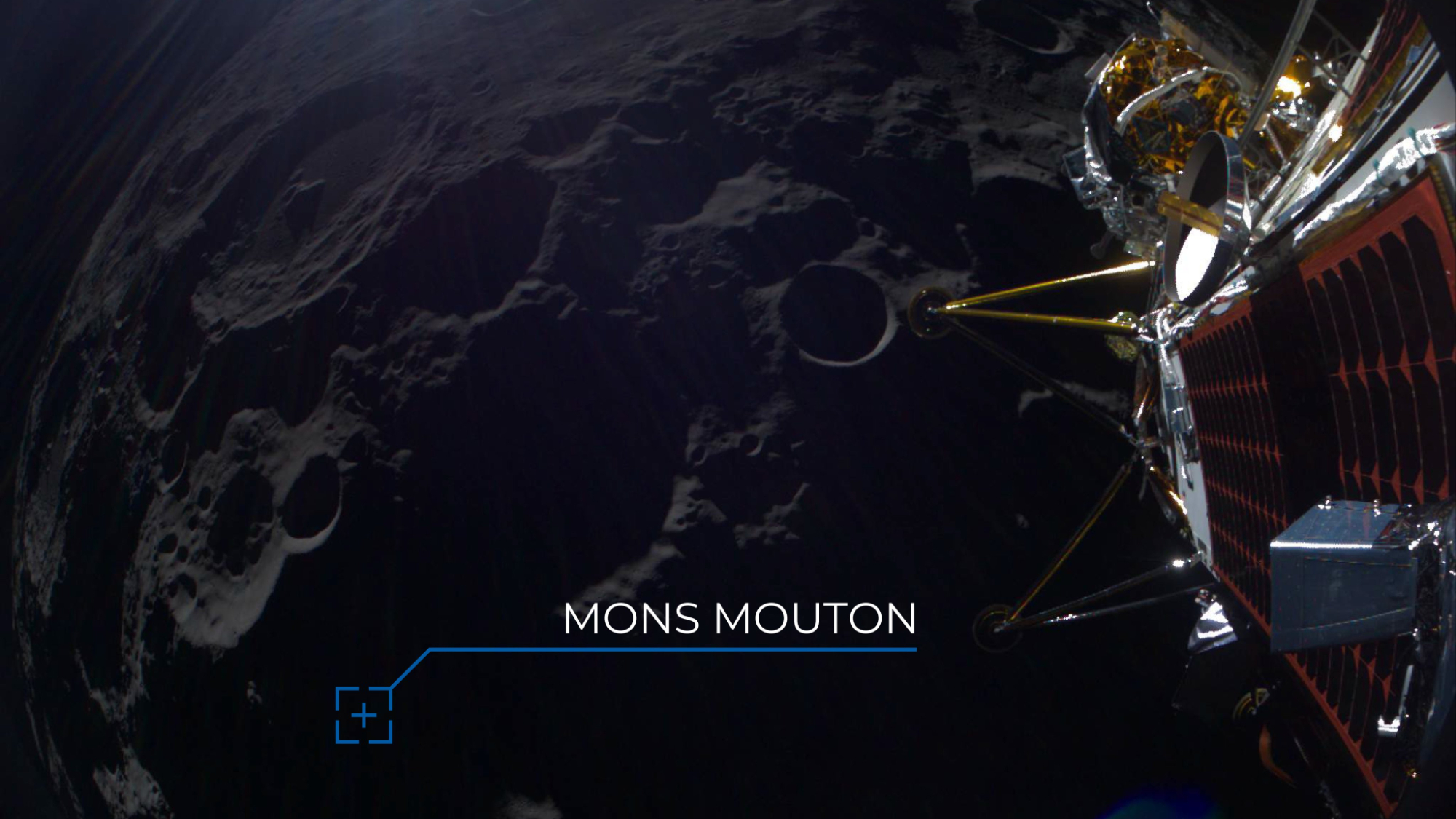

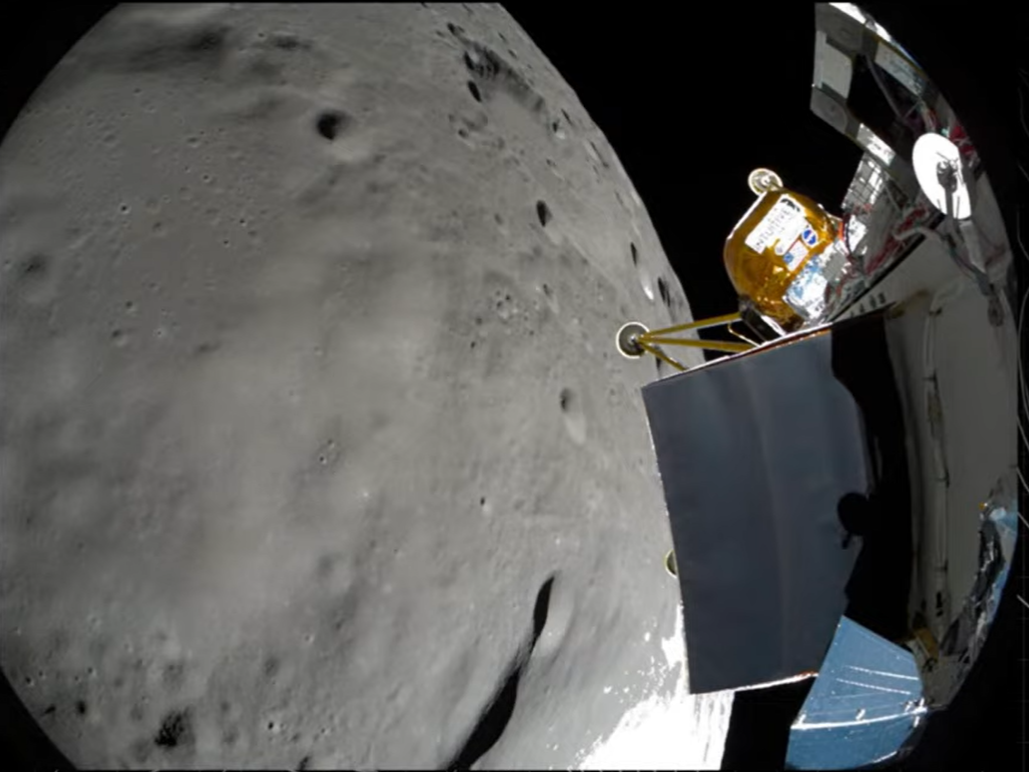

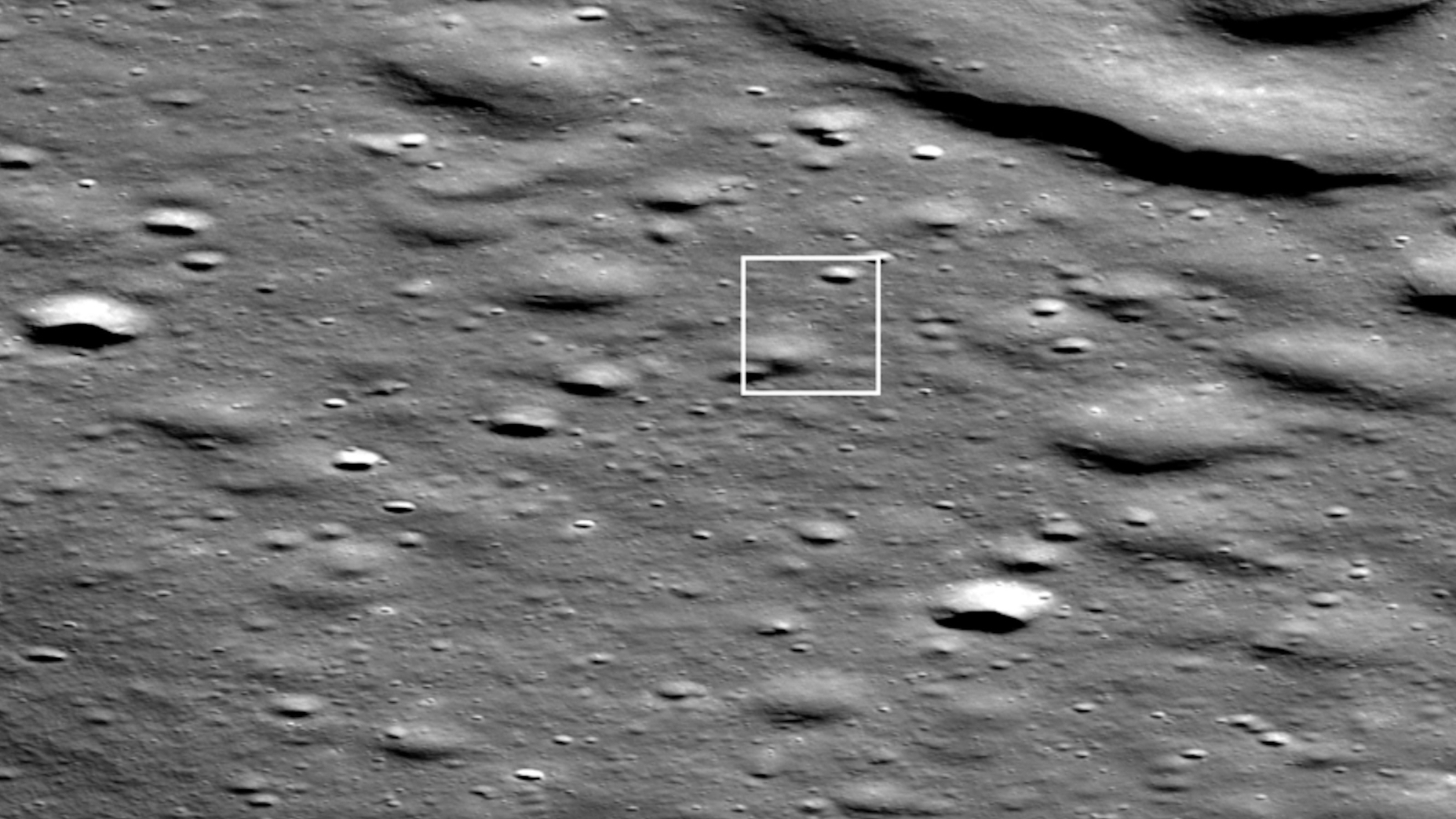

When the Chandrayaan-3 mission touched down on the moon in August 2023, one of the first things it did was measure the surface temperature. The results—detailed in a study published March 6 in the journal Communications Earth and Environment—were both unexpected and intriguing. They also raise tantalizing implications for the biggest lunar question of all: how much water is up there?

During the Chandra’s Surface Thermophysical Experiment (ChaSTE), the spacecraft took the first measurements of this kind since those taken by the Apollo missions over half a century ago. While Apollo landed near the moon’s equator, Chandrayaan touched down at a latitude of 69 degrees north—well into the moon’s previously unexplored polar regions.

Scientists expected the surface temperature on this part of the moon to be in the region of 330 degrees Kelvin (around 57 degrees Celsius or 134 degrees Fahrenheit.) The landing site was significantly hotter: a scorching 355ºK (82°C or just under 180°F), at least 20ºK higher than predicted. However, barely a meter away, the surface temperature was only 332ºK (59°C or 138°F). That’s still hot, but much less so than the landing site and more in line with what scientists expected.

Such a dramatic difference in a distance of just over three feet turns out to be explained by one simple fact. Chandrayaan-3 ended up perched on a shallow slope, at an angle of about 6° toward the equator. The cooler region, meanwhile, was essentially flat. It seems difficult to believe that this relatively small difference in slope could explain such a large difference in temperature. According to K. Durga Prasad—a study co-author and a Faculty Member at the Planetary Sciences Division of the Indian Government’s Department of Space, the measurements actually illustrate two important facts about the moon.

The first is that the lunar surface is covered by a thin layer of dust and rock fragments, known as the “fluff layer.” This layer is characterised by its “very low thermal conductivity and high porosity,” Prasad tells Popular Science. In other words, it’s exceptionally bad at conducting heat. This poor conductivity means that heat does not diffuse across the surface—if a piece of ground is hot, it stays hot, even if it’s right next to a relatively cold area.

Whether a piece of ground is hot, Prasad says, depends on the “incident solar flux,” or how much sunlight falls on it. Given the lack of trees or other sources of shade on the moon, the key factor here is topography. If the rest of the terrain is on an equal level, a piece of ground that slopes away from the sun will be colder than one that slopes toward the sun. Just as importantly, as the angle of the slope increases, so does its effect on the incident solar flux.

[Related: The moon was once covered in an ocean of magma: new data supports theory.]

Crucially, this last effect depends on latitude. As you move away from the equator, the angle at which the sun’s rays strike the moon becomes more oblique—and so does the degree to which a given variation in the angle of a slope will have on the amount of sunlight that slope receives. At the moon’s poles, even small variations in topography can make for significant differences in surface temperature—as demonstrated neatly by Chandrayaan-3’s landing site measurements.

But how does all this relate to the amount of water that may or may not be present on the moon? According to Prasad, there are two factors that created the large temperature in those measurements—poor surface thermal conductivity and increasing sensitivity to topographic variation away from the equator. Both of these also affect the moon’s subsurface temperature, which plays a large role in determining the moon’s ability to accumulate and retain water.

The fluff layer’s poor thermal conductivity also means that heat has a hard time propagating downward into the lunar regolith. This lack of heat creates a significant difference between the temperature of the surface and the temperature of rock that’s only a few inches down. The thickness of the fluff layer at a given point is the dominant factor in determining the difference between the surface and subsurface temperatures.

“Due to the low conductive nature of the surficial layer, heat…propagates very slowly to the subsurface, [and] a large temperature difference is seen between the surface and subsurface temperatures,” Prasad says.“On the other hand, [where] the thermal conductivity is high, the heat propagates faster into the subsurface, resulting in [a relatively small] temperature difference.”

The subsurface temperature is important when it comes to water. It’s one of several factors that affect the accumulation of water ice, but according to Prasad, “the main point is not just accumulation of water, but [the] migration [of water[ to the subsurface and [it] staying put for longer periods of time.” These processes, he says, are largely dependent on temperature, both at the surface and below.

Scientists have long predicted that whatever water might be present on the moon would most likely be found at the lunar poles. However, this new study uses the Chandrayaan-3 data to suggest that there might also be more water in the regions surrounding the poles. The terrain in these regions that has a large enough slope away from the sun—about 14°, according to the calculations in the paper—might be just as good places for water as the actual poles themselves.

[Related: Why scientists think it’s time to declare a new lunar epoch.]

“The present study indicates that [such locations] offer a similar environment as polar sites for accumulating water ice at shallow depths,” says Prasad.

So how much “extra” water might be present? That’s difficult to say and it’s certainly not as simple as multiplying the extra depth by the surface area of suitable slopes.

“The whole process of accumulation and storage of water-ice,” Prasad says, “is quite complex.”

Nevertheless, the data gathered by the Chandrayaan-3 mission is already allowing for improved models of the migration and stability of the water-ice for different representative locations on the moon. Ultimately,the paper demonstrates just how important it is for astronomers to gather data first-hand.

“Based on the temperature profiles from ChaSTE as ground truth, [we] can model the migration and stability of the water ice for different representative locations on the moon,” says Prasad. “[The aim is] to obtain a comprehensive understanding and distribution of water ice on the moon.”

The post New evidence for water lurking under the moon’s poles appeared first on Popular Science.