How to see the upcoming ‘blood moon’ total lunar eclipse

The full moon will take on a red in the wee hours of the morning on March 14. The post How to see the upcoming ‘blood moon’ total lunar eclipse appeared first on Popular Science.

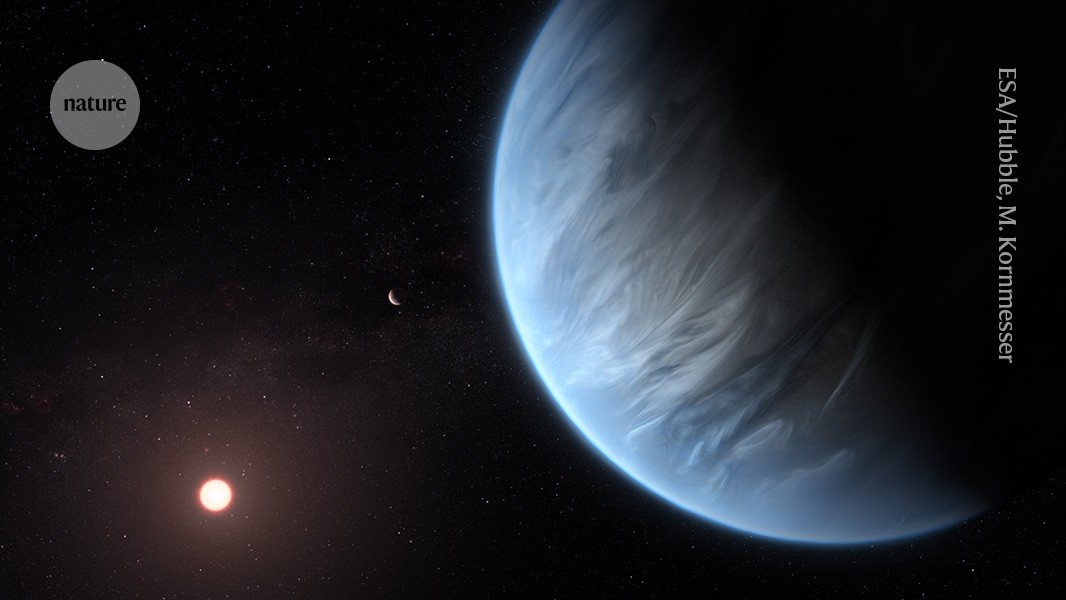

On the night of March 13 into March 14, skygazers across North America—along with many other parts of the world—will get the chance to see a total lunar eclipse with a red ghoulish hue. This is basically the opposite of a solar eclipse, like last year’s spectacular event. Here’s what you need to know to catch all the mid-March lunar action.

How can I watch the lunar eclipse?

Happily, catching a lunar eclipse is a significantly more straightforward task than figuring out how to see the solar equivalent. Basically, at any given moment, half of the planet is looking toward the moon–and if you happen to be on that half of the planet during the night of the eclipse, you need only look to the moon to see the show.

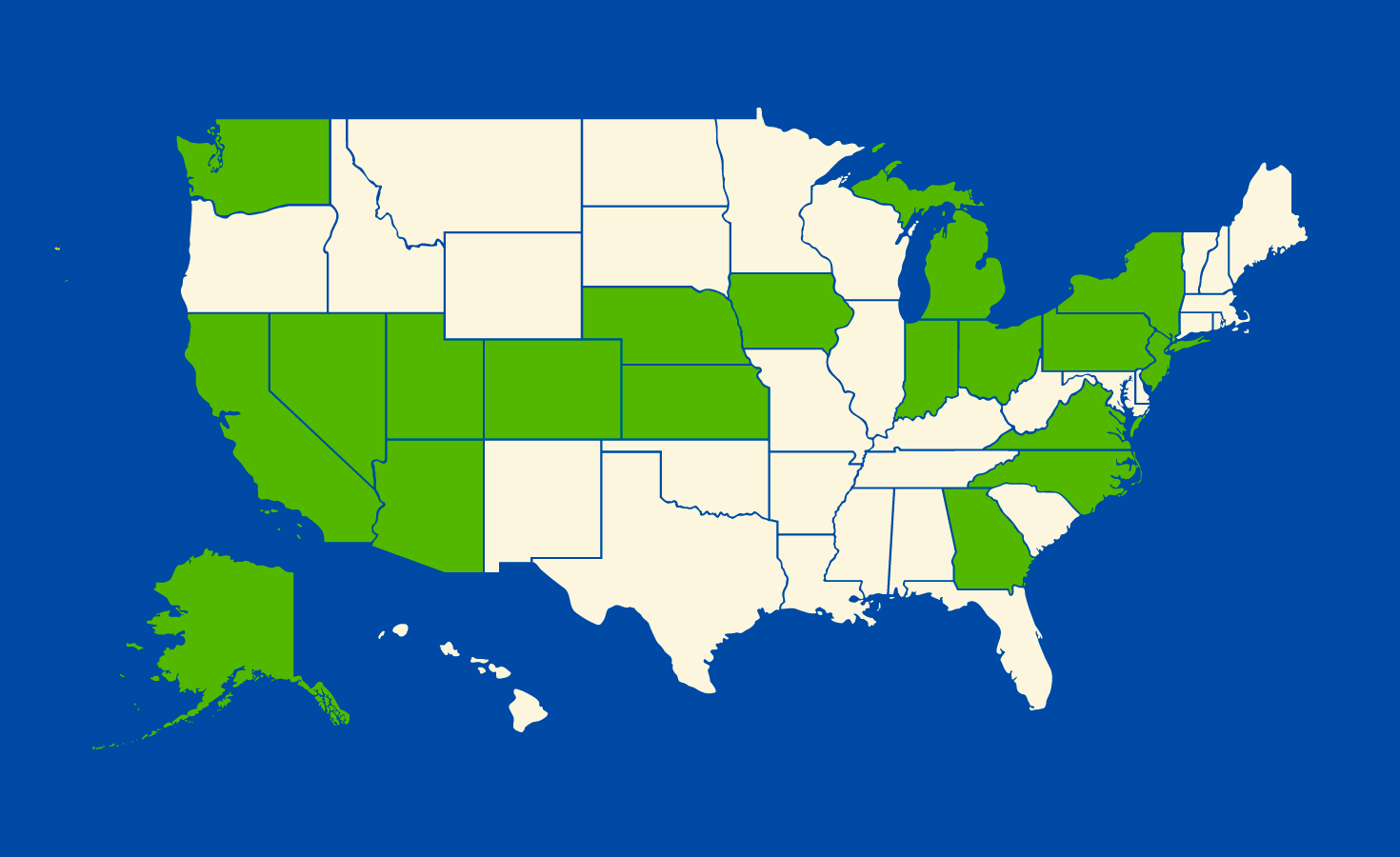

As far as this eclipse goes, you’ll need to be in the planet’s Western Hemisphere.

If you’re in North America, NASA says that this is when you should begin to look skyward:

1:09 a.m. EDT: The moon begins to enter the earth’s umbra (i.e. its shadow.) At this point the red coloration will be hard to see because it will be overpowered by the sunlight reflecting from the uncovered portion of the moon’s disc.

2:26 a.m. EDT: Totality begins! The entire moon is covered by the earth’s shadow, and the characteristic red coloration is on full display. If you want to take photographs, get out the telescope, or just bask in the strange red moonlight, you’ll have around an hour to do so.

3:31 a.m. EDT: Totality ends. The moon’s disc begins to pass out of the earth’s shadow, and the red color of the occluded region begins to fade.

4:47 a.m. EDT: The moon exits the moon’s umbra. It will remain in the penumbra (partial shadow) for another hour or so, but the effect will be subtle and difficult to see.

Lunar eclipse vs. solar eclipse

A solar eclipse happens when the moon passes directly between the Earth and the sun. A lunar eclipse occurs when the Earth passes directly between the sun and the moon.

In both cases, the body in the middle casts a shadow onto the one furthest from the sun. In a solar eclipse, this results in the shadow of the moon sweeping across the Earth’s surface, plunging whatever falls completely within this shadow into a brief period of darkness.

Since the Earth is much bigger than the moon, the planet’s shadow covers the moon completely during a lunar eclipse like the one next week. You might expect this to result in the moon disappearing completely from the sky, but that isn’t what happens. Instead, the moon remains visible, but its color changes, deepening from its familiar silvery-white into a deep, blood red—which explains why lunar eclipses are also referred to as “blood moons.”

Why does the moon appear red in a lunar eclipse?

During a lunar eclipse, the only light that reaches the moon is light that has traveled through our atmosphere. Since red light is the most likely to emerge on the other side that is what illuminates the moon, making it appear a rusty color.

But why the red light? To answer this question, we need to consider a key property of light: its wavelength. Understanding wavelength can help answer life’s other pressing questions, such as, “Why is the sky blue?”, “Why are sunsets so colorful?”, and “Why is my neighbor’s stereo so annoying?”.

Like any other wave, light waves have peaks and troughs. The distance between two such peaks (or troughs) is the light’s wavelength, and this figure can tell us a great deal about a wave’s properties.

The most familiar consequence of light’s wavelength is whether we can see it or not. Our eyes are sensitive to some wavelengths—specifically, waves with wavelengths between 380 nanometers and 750 nanometers, which we call the “visible spectrum.” At one end of this spectrum is violet light, with a wavelength around 380 nanometers. At the other is red light, with a wavelength extending up to about 750 nanometers.

Wavelength is related directly to other important aspects of a light ray, like its frequency and the energy it carries. Broadly, the lower the wavelength, the more energy a light ray carries. This, in turn, determines another property that will be important for understanding the moon’s color: the angle at which light is refracted when it moves from one medium into another.

A classic demonstration of this phenomenon is shining white light into a prism. While white light appears colorless, it actually contains a mad jumble of all possible wavelengths. When the beam enters the prism, each wavelength is refracted at a slightly different angle. The same thing happens when the light emerges, and the result—as anyone who studied high school physics and/or is a fan of Pink Floyd will know—is the appearance of a lovely colorful spectrum, sorted neatly by wavelength.

[ Related: Hubble just captured a lunar eclipse for the first time ever. ]

During a lunar eclipse, no direct sunlight reaches the moon. However, we can see the moon, so some light clearly strikes its surface. So where does that light come from? Well, just like a prism, the Earth’s atmosphere refracts light. Some of the light that arrives from the sun is refracted toward the moon, allowing us to see the moon during a lunar eclipse.

The immediate question, of course, is why that light is red. The basic answer is that blue light has a relatively hard time making it through the Earth’s atmosphere, while red light passes through relatively untouched.

Why does red light travel through the atmosphere more easily?

A phenomenon called Rayleigh scattering makes it so that red light has a better time reaching Earth’s atmosphere than blue light. Since the atmosphere is a relatively thin halo of gases, its interaction with light is much more complicated than the interaction between a beam of white light and a prism. In the atmosphere, the key interactions are between individual photons and gas molecules.The photons are bounced around between gas molecules like tiny atomic bumper cars.

This process might sound somewhat abstract, but it also explains something humans have been wondering ever since they first looked skyward: why is the sky blue? If you look carefully at the spectrum created by a prism you’ll see that red light emerges at the top of the spectrum, on a trajectory closest to that of the original ray. Blue light, by contrast, bends sharply.

[ Related: To set the record straight: Nothing can break the speed of light. ]

Something similar happens in the atmosphere.The shorter a light’s wavelength, the more likely it is to interact with the substance through which it is traveling. This means that blue light is more likely to be scattered than red light. The situation is not unlike the way that while earplugs block out the higher end sounds of your annoying neighbor’s stereo. The low bass frequencies still remain all too audible.

The result is on display when we go outside on nice days. The sky’s blue coloration results from blue light being scattered by the atmosphere.

Where is this red light when the moon isn’t being eclipsed?

We technically see this red light twice a day at sunrise and sunset. During these times, the light needs to travel farthest through the atmosphere to reach an Earth-based observer.

In a way what we’re really seeing when we gaze up at a deep red blood moon is the same light that makes our sunsets so spectacular. Or as NASA puts it, the color of a lunar eclipse is “as if all the world’s sunrises and sunsets [were] projected onto the Moon.” Gorgeous.

The post How to see the upcoming ‘blood moon’ total lunar eclipse appeared first on Popular Science.

.jpg)

![The breaking news round-up: Decagear launches today, Pimax announces new headsets, and more! [APRIL FOOL’S]](https://i0.wp.com/skarredghost.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/lawk_glasses_handson.jpg?fit=1366%2C1025&ssl=1)