Gladiator bones finally confirm human-animal combat in Roman Europe

These 'beast hunts' pitted armed human performers against lions, boars, bears, and more. The post Gladiator bones finally confirm human-animal combat in Roman Europe appeared first on Popular Science.

Archeologists in the UK and Ireland recently uncovered a rare find: the skeletal remains of a gladiator from Roman-era England. The bones not only help experts better understand the lives of fighters—they reveal who they fought against for the crowds’ entertainment. And according to a study published April 23 in the journal PLOS One, the skeleton displays the first-ever evidence of human-animal combat in Europe during the Roman Empire.

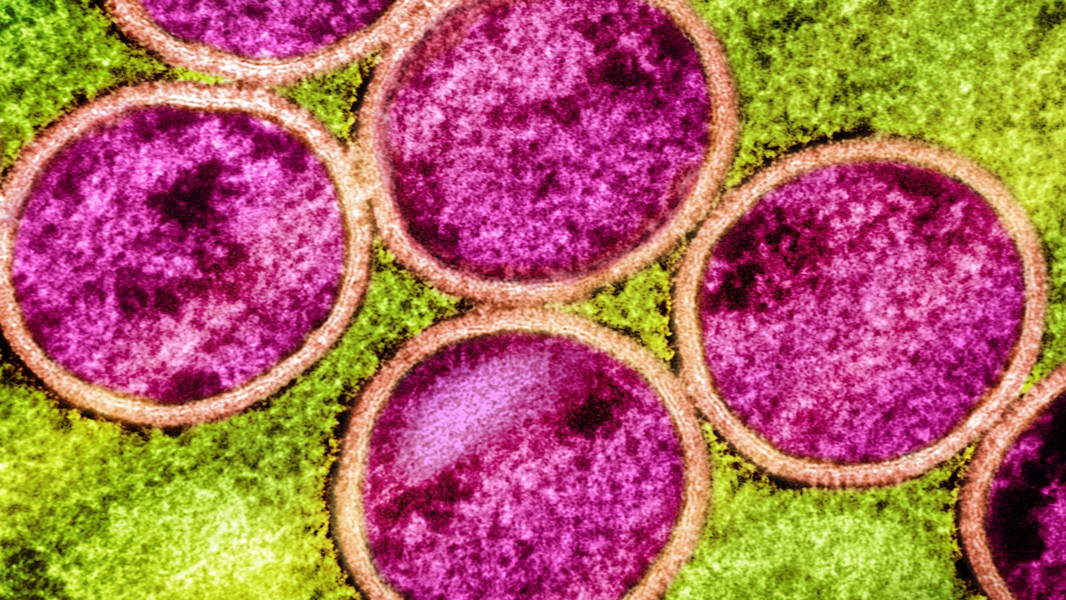

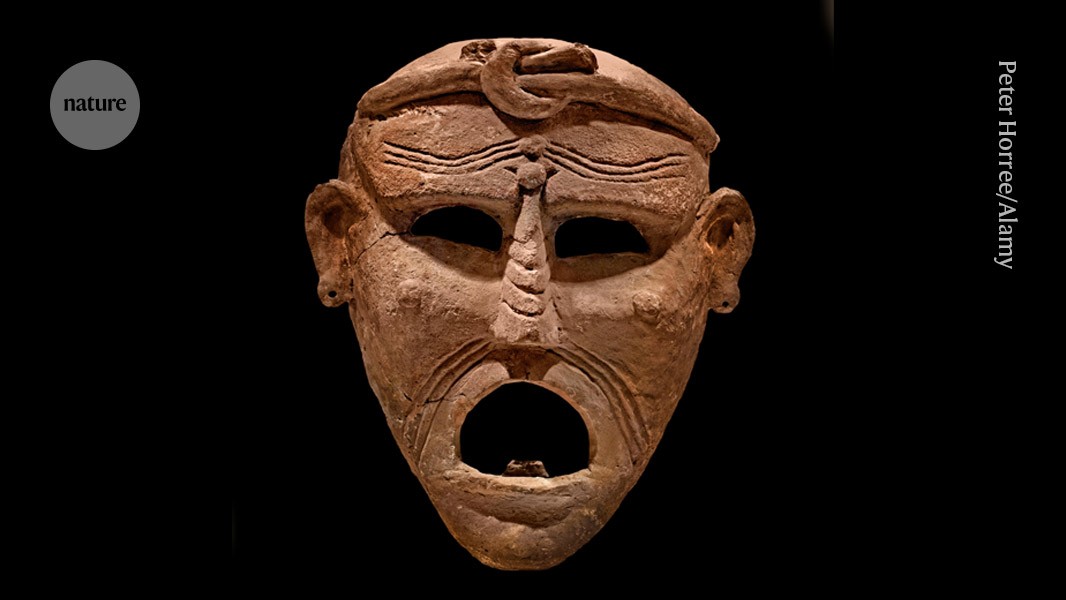

Gladiator combat is a well-documented aspect of ancient Roman society, but the physical remains of fighters have remained elusive. Due to this lack of bodily evidence, experts have instead long relied on historical accounts, artifacts, and artwork to learn about gladiator combats. Contemporary textual evidence indicates that in addition to humans, organizers forced combatants and prisoners to face large animal predators. Events known as “venationes” (beast hunts) pitted trained and armed human performers against lions, boars, bears, elephants, and other animals. Meanwhile, “damnatio ad bestios” battles focused on reenacting mythical stories involving wild animals, often as backdrops for public executions.

Despite written evidence and physical relics like weapons and armor, the lack of forensic information made it especially challenging for historians and archeologists. For example, it remained unclear if gladiator matches held as much importance in Roman-occupied regions like Britain as they did in Rome itself. Images of these spectacles survive to the present-day, but no direct links have supported human-animal gladiator matches in Roman Britain. However, analysis of a man’s skeleton excavated near York appears to finally offer concrete confirmation of the gruesome entertainment.

According to study authors, the remains were initially discovered during a city development project nearly two decades ago in a larger gravesite. Recent bioarcheological examination and isotopic analysis indicated the individual was a 26-35 year old local at the time of his death, and was buried around 200-300 CE near Eboracum, the Roman city that preceded York. His cause of death starkly contrasted with other nearby remains.

Experts previously noted a number of depressions on his pelvis resembling carnivore bites. After creating a three-dimensional scan of the area, researchers then compared the indentations to various animals’ teeth marks. Additional consultation from zoologists confirmed a large cat such as a lion likely caused the injuriesby. Given their placement, the study authors also theorized the bites occurred as the predator was scavenging the body around his time of death.

“The implications of our multidisciplinary study are huge,” Maynooth University professor of archeology and study lead author Tim Thompson said in a statement. “Here we have physical evidence for the spectacle of the Roman Empire and the dangerous gladiatorial combat on show. This provides new evidence to support our understanding of the past.”

David Jennings, CEO of the independent charity organization York Archeology that contributed to the study, said the newest findings also spoke to the latest advancements in the field.

“One of the wonderful things about archaeology is that we continue to make discoveries even years after a dig has concluded,” he said. “It is now 20 years since we unearthed 80 burials at Driffield Terrace. This latest research gives us a remarkable insight into the life–and death–of this particular individual, and adds to both previous and ongoing genome research into the origins of some of the men buried in this particular Roman cemetery.”

The first proof of human-animal combat in Roman Britain also helps clarify and situate regional culture during this time period.

“As tangible witnesses to spectacles in Britain’s Roman amphitheatres, the bitemarks help us appreciate these spaces as settings for brutal demonstrations of power,” explained John Pearce, a study co-author and classics professor at King’s College London. “They make an important contribution to desanitizing our Roman past.”

“We may never know what brought this man to the arena where we believe he may have been fighting for the entertainment of others,” added Jennings. “But it is remarkable that the first osteo-archaeological evidence for this kind of gladiatorial combat has been found so far from the Colosseum of Rome.”

The post Gladiator bones finally confirm human-animal combat in Roman Europe appeared first on Popular Science.