Drug turns human blood into poison for mosquitoes

"...using nitisinone could be a promising new complementary tool for controlling insect-borne diseases like malaria."

Researchers have discovered that when patients take the drug nitisinone, their blood becomes deadly to mosquitoes.

In the fight against malaria, controlling the mosquito population is crucial.

Several methods are currently used to reduce mosquito numbers and malaria risk. One of these includes the antiparasitic medication ivermectin. When mosquitoes ingest blood containing ivermectin, it shortens the insect’s lifespan and helps decrease the spread of malaria.

However, ivermectin has its own issues. Not only is it environmentally toxic, but also, when it is overused to treat people and animals with worm and parasite infections, resistance to ivermectin becomes a concern.

Now, the new study in Science Translational Medicine has identified another medication with the potential to suppress mosquito populations to help control malaria.

“One way to stop the spread of diseases transmitted by insects is to make the blood of animals and humans toxic to these blood-feeding insects,” says Lee R. Haines, associate research professor of biological sciences at the University of Notre Dame, honorary fellow at the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine and co-lead author of the study.

“Our findings suggest that using nitisinone could be a promising new complementary tool for controlling insect-borne diseases like malaria.”

Typically, nitisinone is a medication for individuals with rare inherited diseases—such as alkaptonuria and tyrosinemia type 1—whose bodies struggle to metabolize the amino acid tyrosine. The medication works by blocking the enzyme 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate dioxygenase (HPPD), preventing the build-up of harmful disease byproducts in the human body.

When mosquitoes drink blood that contains nitisinone, the drug also blocks this crucial HPPD enzyme in their bodies. This prevents the mosquitoes from properly digesting the blood, causing them to quickly die.

The researchers analyzed the nitisinone dosing concentrations needed for killing mosquitoes, and how those results would stack up against ivermectin, the gold standard ectoparasitic drug (medication that specifically targets ectoparasites such as mosquitoes).

“We thought that if we wanted to go down this route, nitisinone had to perform better than ivermectin,” says Álvaro Acosta Serrano, professor of biological sciences at Notre Dame and co-corresponding author of the study.

“Indeed, nitisinone performance was fantastic; it has a much longer half-life in human blood than ivermectin, which means its mosquitocidal activity remains circulating in the human body for much longer. This is critical when applied in the field for safety and economical reasons.”

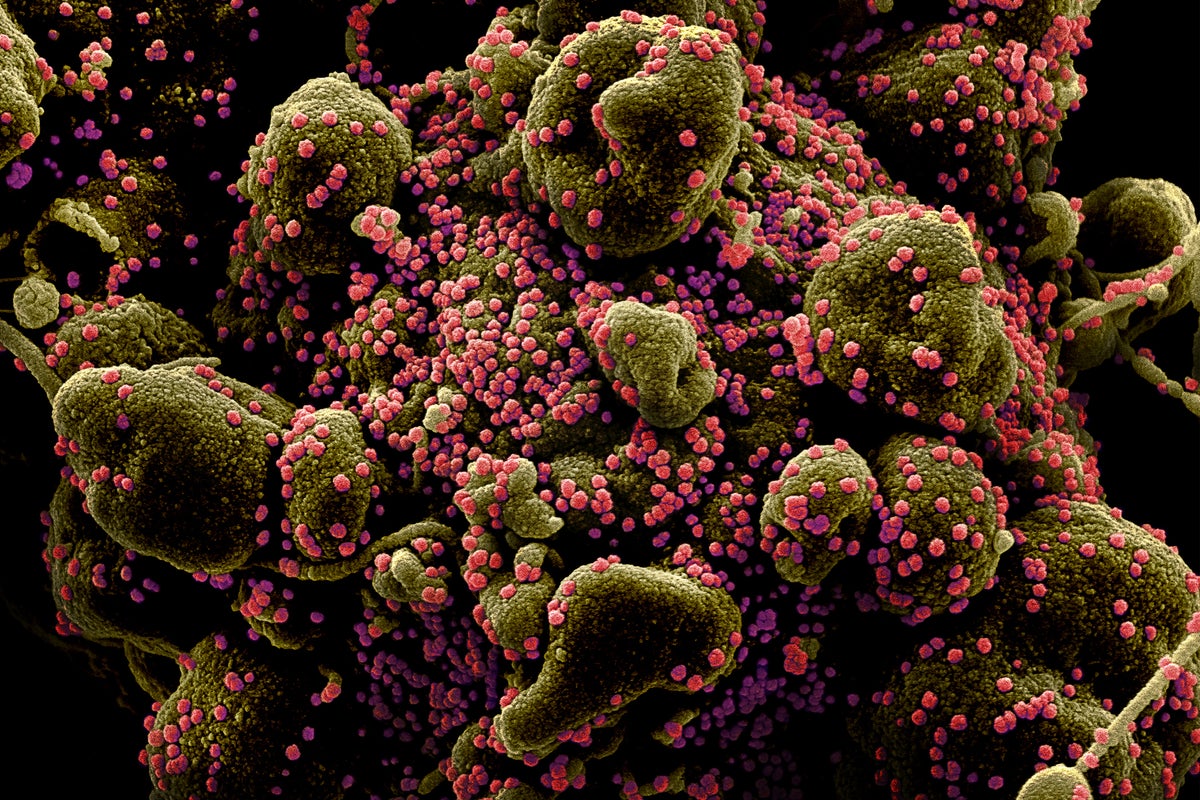

The research team tested the mosquitocidal effect of nitisinone on female Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes, the primary mosquito species responsible for spreading malaria in many African countries. If these mosquitoes become infected with malaria parasites, they spread the disease when they feast on a human.

To evaluate how the drug affected the mosquitoes when fed fresh human blood containing nitisinone, researchers collaborated with the Robert Gregory National Alkaptonuria Centre at the Royal Liverpool University Hospital. The center was performing nitisinone trials with people diagnosed with alkaptonuria, who then donated their blood for the study. Those taking nitisinone were found to have blood that was deadly to mosquitoes, which Haines describes as having a “hidden superpower.”

The research team collected data on how the drug was metabolized in peoples’ blood, allowing the team to fine-tune their modeling and provide pharmacological validation of nitisinone as a potential mosquito population control strategy.

Nitisinone was shown to last longer than ivermectin in the human bloodstream, and was able to kill not only mosquitoes of all ages—including the older ones that are most likely to transmit malaria—but also the hardy mosquitoes resistant to traditional insecticides.

“In the future, it could be advantageous to alternate both nitisinone and ivermectin for mosquito control,” Haines says. “For example, nitisinone could be employed in areas where ivermectin resistance persists or where ivermectin is already heavily used for livestock and humans.”

Next, the research team aims to explore a semi-field trial to determine what nitisinone dosages are best linked to mosquitocidal efficacy in the field.

“Nitisinone is a versatile compound that can also be used as an insecticide. What’s particularly interesting is that it specifically targets blood-sucking insects, making it an environmentally friendly option,” Acosta Serrano says.

As an unintended benefit, extending the use of nitisinone as a vector control tool could consequently increase drug production and decrease the price of the medication for patients suffering from rare genetic diseases in the tyrosine metabolism pathway.

Additional coauthors are from the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, the University of Glasgow Wellcome Centre for Integrative Parasitology, the Medicines for Malaria Venture, the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, and the Royal Liverpool University Hospital.

Funding for the study came from the UK Medical Research Council, Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council, Wellcome Trust Institutional Strategic Support Fund, the Medical Research Council Doctoral Training Partnership and the University of Glasgow Wellcome Centre for Integrative Parasitology.

Source: University of Notre Dame

The post Drug turns human blood into poison for mosquitoes appeared first on Futurity.

.jpg?#)