A steady gaze may set you up for better performance

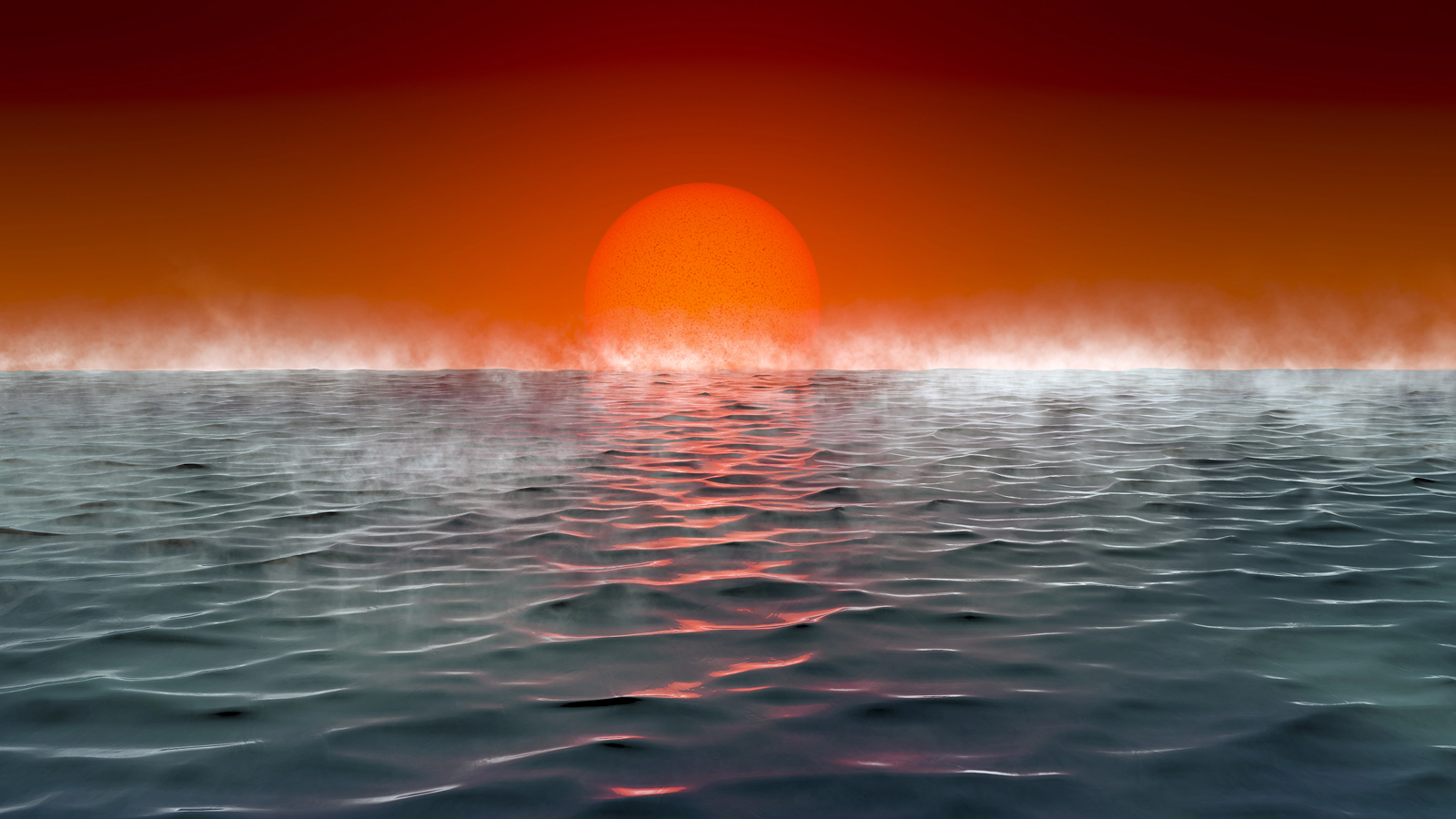

New research documents a phenomenon in eye movement that links a steady, focused gaze with superior levels of performance.

New research identifies the links between a steady gaze and elite performance.

In his book on basketball great Bill Bradley, writer John McPhee proposes that Bradley’s greatest asset had little to do with speed, strength, or agility. It had to do, McPhee says, with his eyes.

“His most remarkable natural gift… is his vision,” McPhee observes. “During a game, Bradley’s eyes are always a glaze of panoptic attention.”

The work of University of Notre Dame researcher Matthew Robison suggests that McPhee may have been onto something.

In a recent study supported by the US Naval Research Laboratory and the Army Research Institute Robison documented a phenomenon in eye movement—or “oculomotor dynamics”—that links a steady, focused gaze with superior levels of performance.

Robison, an assistant professor in the psychology department, made the discovery thanks to the unique capabilities of his lab, which includes over a dozen precision instruments for tracking eye movement and pupil dilation. These devices capture images of the eyes every four milliseconds, providing 250 frames per second.

This ultra-detailed look at the eyes allows Robison to “read” the complex language of minute eye movement. A slight wiggle in the eye, for example, can reveal that a study participant was distracted by a stimulus entering their field of vision—even though their facial expression never altered. Or a dilation of the pupil might indicate a participant is struggling to solve a complex math problem.

Recently, though, Robison has been most interested not in why our eyes move, but in why we might—or might want to—keep them still. He was inspired to investigate the meaning of a steady gaze by the work of applied sports psychologists helping athletes achieve high levels of performance.

“Sports psychologists regularly advise that if you’re about to putt, pick a spot on the back of the golf ball and keep your eyes still there for a second or two. Then hit the ball,” Robison explains.

“Or if you’re shooting a free throw in basketball, pick a spot on the rim and focus on it for a few seconds. Then shoot the free throw. The advice seems sound in many cases. But the causal pathway behind this phenomenon has not been thoroughly demonstrated or explained.”

Robison hypothesized that a steady gaze had to do with attention control and thus would lead to better performance not only in sports but also in almost any mentally demanding activity, whether it was comprehending a difficult passage of text, solving a complex problem, remembering new information, or multitasking.

To test his hypothesis, he recruited nearly 400 participants to perform a series of tasks in his lab over a two-hour period while their gaze was being recorded by eye trackers and pupilometers.

Robison found that across the board, those participants who kept their gaze steady in the moments just before being called upon to complete a task performed with greater speed and with greater accuracy. Borrowing a term from sports psychologist Joan Vickers, Robison called this specific quality of gaze “quiet eye.” He says it is more than a lack of motion; like Bradley’s gaze that so impressed McPhee, “quiet” eyes are not just still. They are focused—able to resist distractions and remain vigilant, ready, and “awake.”

His work documenting quiet eye suggested another question for Robison to explore: Would it be possible to train individuals to perform better by training them not in the task itself but in developing a steadier gaze?

Thanks to new funding from the Office of Naval Research (ONR), Robison launched a new three-year project focused on answering that question. The funding is part of the ONR’s Young Investigator Award program, and Robison is one of just 25 awardees of the program over the past year. The funding will allow Robison to test new ways to train one’s gaze and to determine how far the effects of “quiet eye” reach.

“Our aim is to make the benefits of ‘quiet eye’ available to anyone who wants to learn them,” he says.

And while it will not immediately lead to Bill Bradley-levels of basketball virtuosity, the benefits could be widespread. Robison hopes that “those who learn this skill are able, in turn, to sustain and control their attention, which will yield benefits for their performance in almost any complex or demanding task.”

Natalie Steinhauser, a Program Officer at Office of Naval Research, says she looks forward to starting this new research that bridges two aspects of her Prepared Warfighter Portfolio. Her portfolio focuses on “understanding attention control and how it impacts warfighter performance” and “accelerating and innovating training approaches to maximize warfighter readiness.” This research, she says “brings those worlds together in hopes of training our naval warfighters to optimize their attention and thus performance.”

This pre-print paper has not undergone peer review and its findings are preliminary.

Source: University of Notre Dame

The post A steady gaze may set you up for better performance appeared first on Futurity.

.jpg?#)