Carbon capture hits a growth spurt as financial and other factors align

Air Products and Microsoft are among the firms driving the growth of point-source capture and sequestration, even as criticisms of the technology linger. The post Carbon capture hits a growth spurt as financial and other factors align appeared first on Trellis.

For much of the past two decades, the loudest voices in the debate over carbon capture and storage (CCS) were often the critics: The equipment was too expensive or too prone to breaking down. Perhaps most damning was the accusation that the technology would extend the life of fossil fuels and delay cleaner, longer-term solutions.

Now the dynamics have shifted. CCS projects are growing at record rates. The technology continues to improve, economic incentives have aligned and the growth of AI and data centers has increased demand. The critics have not been mollified, but the momentum is with the industry — suggesting that any company with hard-to-abate emissions in its supply chain should engage with the arguments.

“It’s been like a snowball rolling down a hill in terms of corporate interest and investment in the sector,” said Jessie Stolark, executive director of the Carbon Capture Coalition, an industry group.

Global growth

CCS offers a seemingly simple decarbonization solution: Rather than replace coal power stations, steel plants and other facilities that rely on fossil fuels, why not capture and store the carbon dioxide that the infrastructure emits? In many cases, this involves pushing the gas over an absorbent material, compressing the captured CO2 and piping it to a geological reservoir for permanent storage.

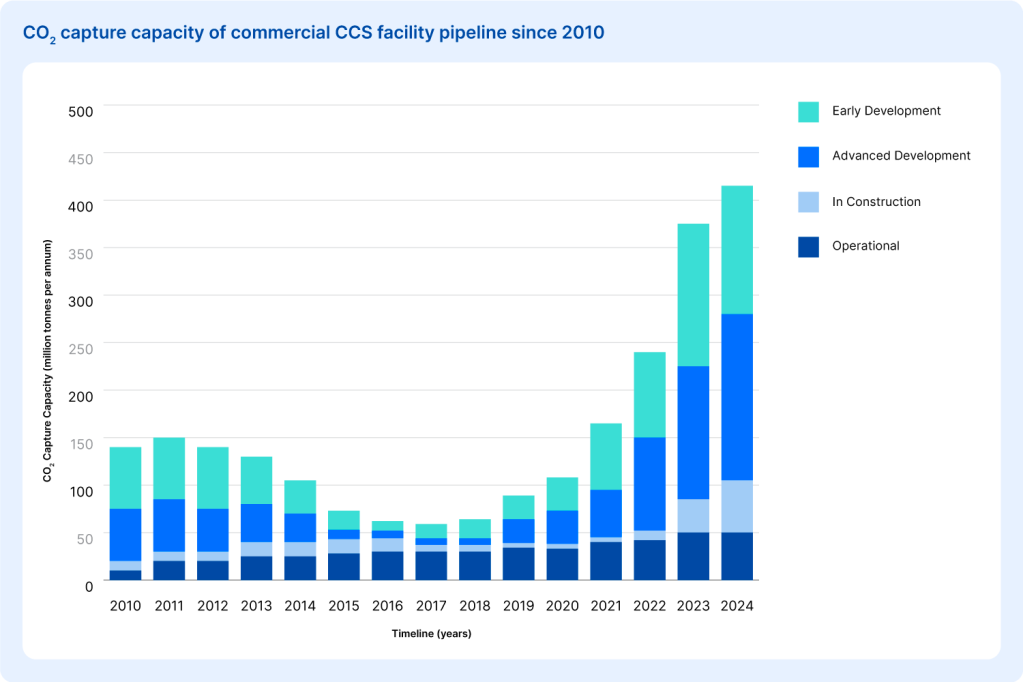

The idea is simple, but during the first half of the 2010s high costs and technological setbacks led to a decline in the capacity of projects in development. Then the tide turned. A federal CCS tax credit, known as 45Q, was made more valuable in 2018 and more valuable still, as part of the Inflation Reduction Act, in 2022. The number of projects operational or in development globally grew from 392 to 628 between 2023 and 2024, according to the Carbon Capture Coalition. The U.S. is the leader, with more projects than the next four countries — the U.K., Canada, Norway and China — combined.

The Louisiana Clean Energy Complex, a hydrogen production facility under construction in Ascension Parish, illustrates the trend. Air Products, the industrial giant behind the project, says that 95 percent of the 5 million tons of CO2 emitted annually by the facility will be captured and stored, which the company claims makes it the world’s largest capture and permanent sequestration project.

Air Products did not return a request for more information, but an analysis published this month by the capture coalition puts capture and storage costs at between $100 and $200 per ton of CO2. The exact price depends on the maturity of the technology used and the concentration of the gas in the waste stream, with higher concentration streams — which includes hydrogen facilities — tending to have lower costs.

More million-ton projects

Other huge projects are coming soon. In early April, a consortium of companies announced plans for an ammonia plant, also in Ascension Parish, that will capture and store more than 2 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. (The parish is part of “Cancer Alley,” a heavily industrialized area with elevated rates of the disease.) Two weeks later, ExxonMobil revealed plans to capture 2 million tons of CO2 from a natural gas power plant near Houston, Texas.

The bullishness of CCS investors is also evident at the 140,000 square-foot factory opened in Burnaby, British Columbia earlier this month by Svante, a manufacturer of filters that capture carbon dioxide from industrial emissions.

The factory can produce enough filters to capture 10 million tons of CO2 annually and its opening follows a $145 million investment round for the company. A confluence of factors is driving the industry forward, said Claude Letourneau, Svante’s CEO, including tax credits and the green premium that some manufacturers can charge for low-carbon commodities, such as hydrogen.

Smaller companies with innovative solutions are waiting in the wings, hoping to ride the industry’s momentum. Carbon Clean, a London-based startup, has designed a capture unit that fits into a shipping container, which it says is half the size of conventional systems.

“The biggest challenge for implementing carbon capture is the real estate,” said Aniruddha Sharma, Carbon Clean’s CEO “Nobody has any space.” Following a successful test at a fertilizer plant in Abu Dhabi, the company is now working on further tests in Saudi Arabia and Canada.

Companies that have emissions from hard-to-abate sources — fertilizer, steel, cement — in their Scope 3 inventory stand to benefit from the reductions that CCS brings. And there are other reasons for sustainability professionals to track the technology, noted Sangeet Nepal, a technology specialist at the Carbon Capture Coalition.

The rising demand for uninterrupted supplies of low-carbon electricity can be met by gas power plants with CCS attached, for example. In December, ExxonMobil announced plans to build a gas and CCS facility in Texas to supply low-carbon electricity to nearby data centers.

CCS technology is also opening up new classes of carbon credits.

Svante is targeting its technology at pulp and paper facilities, some of which are using credit revenue to fund the installation of carbon capture. One recent project was funded by a purchase by Microsoft of credits covering 3.7 million tons of carbon dioxide over 12 years.

Criticisms linger

This progress has changed the narrative around CCS, but it has not altered the opinions of critics. They continue to question the calculations that underlie the claimed climate benefits of CCS, notably around the issue of where to draw boundaries when assessing the impact of the technology.

CCS equipment requires energy, for instance. Most developers hope to use renewables, thus avoiding additional emissions. But there’s an opportunity cost in doing so because those renewables could be used to replace fossil power plants, argued Mark Jacobson, an energy systems expert at Stanford University.

“You can’t just add things to the grid willy nilly,” said Jacobson. “There’s a queue. If you’re adding stuff and using it for carbon capture, you’re not replacing fossils on the grid.”

In one recent study, Jacobson and colleagues compared global decarbonization scenarios in which renewables were used to power either CCS or electrified versions of industrial facilities. After accounting for health costs due to air pollution from continued use of fossil fuels, along with other factors, they found that annual costs in the CCS scenario were at least nine times greater than the electrification alternative. Because CCS systems do not capture all the carbon dioxide that passes through them, atmospheric levels of the gas were also much higher.

Jacobson’s study is global in scope, but individual projects have also been criticized, including Air Products’ hydrogen facility in Louisiana. In a study published in March, researchers at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, a think tank, claimed that the benefits of the project rest on faulty assumptions about the amount of carbon that will be captured, leak rates of the methane feedstock and other factors. Once the assumptions are corrected, claims the institute, the project becomes a heavy emitter.

Just 10 years ago, debate of this nature played a role in slowing the deployment of CCS. But there is a sense among industry insiders that things have changed. The financial case for the technology has been rewritten. And while the Trump administration appears to have no interest in tackling climate change, backing from oil majors and GOP members in states that house capture projects means that CCS might be one decarbonization technology it can get behind.

“We are making the case,” said Stolark, “and we feel that carbon management squarely fits within this administration’s energy dominance framework.”

The post Carbon capture hits a growth spurt as financial and other factors align appeared first on Trellis.