Wolf Man: How Much ‘Man’ Do We Really Want in a Werewolf?

Last September, well before Halloween and a full four months out from Leigh Whannell’s reimagining of a Universal Monsters classic, The Wolf Man, we got our first look at Whannell and Blumhouse Productions’ new take on the famous werewolf. Supposedly. While a theme park performer visibly stood in front of a poster for this January’s […] The post Wolf Man: How Much ‘Man’ Do We Really Want in a Werewolf? appeared first on Den of Geek.

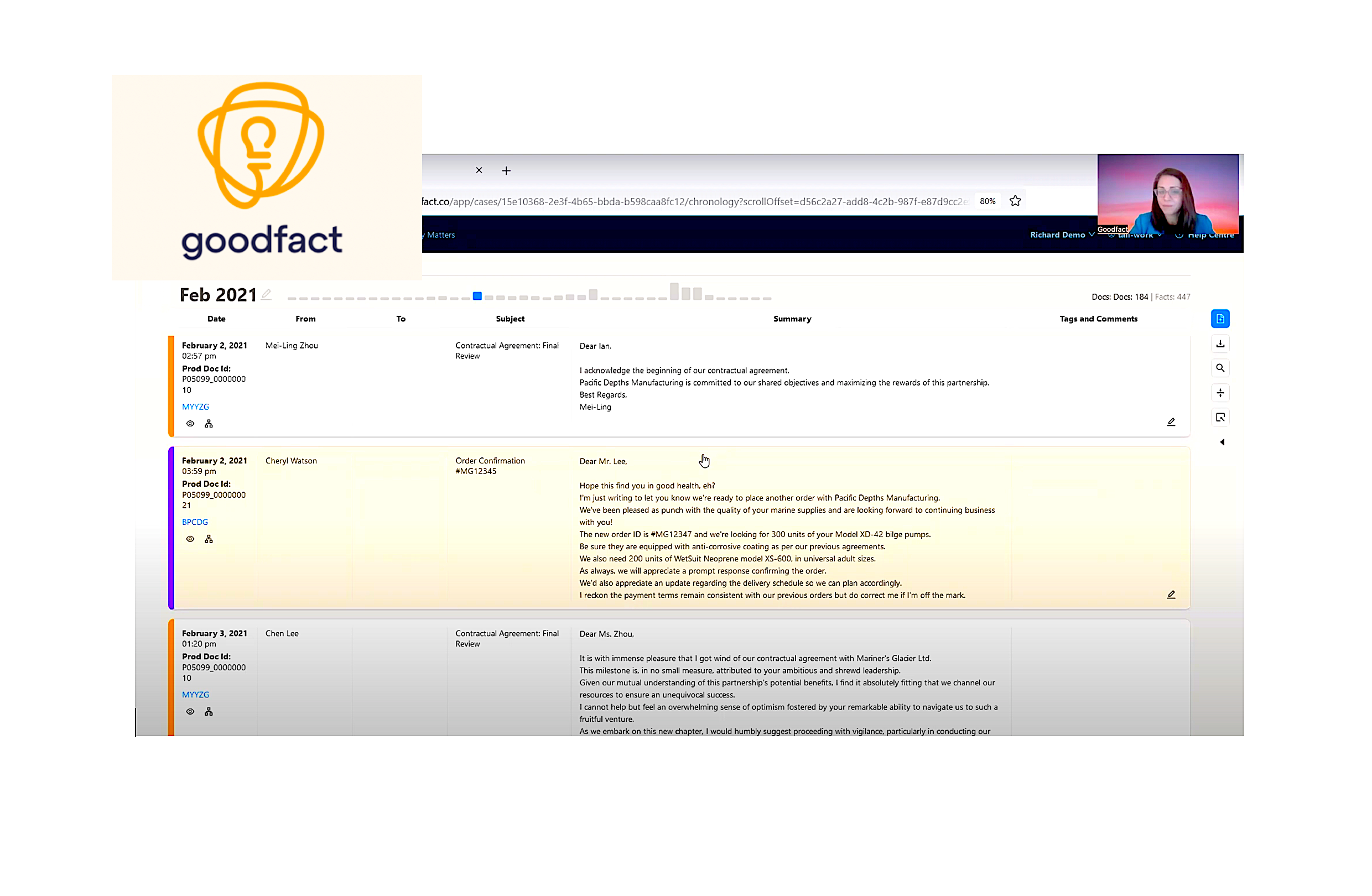

Last September, well before Halloween and a full four months out from Leigh Whannell’s reimagining of a Universal Monsters classic, The Wolf Man, we got our first look at Whannell and Blumhouse Productions’ new take on the famous werewolf. Supposedly.

While a theme park performer visibly stood in front of a poster for this January’s Wolf Man with a goofy-looking latex mask on—presumably it would seem scarier in the dark at Universal Studios’ Halloween Horror Nights for where it was intended —it obviously wasn’t the real deal Whannell and makeup artist Arjen Tuiten (Pan’s Labyrinth) designed for the finished film. Even so, the internet predictably bayed in anger. “That’s not a wolf man!” many seemed to cry. “It’s an old timey mountain man with really long hair and a bad dentist!”

Four months later, the howling is gone and we now know what Whannell and Tuiten actually made. Rest assured, it does not look like Halloween Horror Nights’ Deliverance reject. But it’s also safe to say that it is probably the most human-seeming werewolf we’ve had in decades, even by the virtue of the Wolf Man franchise. Sure, the original The Wolf Man of 1941 canonized the pop culture image of werewolves by having the upright Lon Chaney Jr. be buried underneath yak hair and prosthetic teeth, but even 85 years later it appears more elaborate than the minimalist creature in Whannell’s Wolf Man.

By contrast, when Christopher Abbott steps into the shoes of the doomed protagonist in 2025’s Wolf Man, he barely qualifies as a werewolf at all. The term is noticeably never used in the movie. Instead the creature is given a vaguely Indigenous folk origin, with mutterings about the “Face of the Wolf” being sprinkled into the screenplay. Indeed, the “Face of the Wolf” curse is suggested to be a mere disease that once transmitted needs neither full moon or silver bullets to be controlled.

It simply turns Abbott’s kindly father into a pitifully sick man who gnaws at his wounds like a dog in a trap. It is a deliberate departure, and we can attest anecdotally that the design has left a few colleagues (as well as this writer) underwhelmed. Reimagining the werewolf as a metaphor for sickness is well and good, but if you call your movie WOLF MAN, a certain level of furry iconography is expected. Abbott’s lycanthrope, however, could just as easily be a poor bastard turning into an extra in the next Planet of the Apes.

All of which raises the question of what exactly do viewers want from a big screen werewolf these days? Well, there are two schools of thought…

The O.G. Bipedal Werewolf

Few would argue John Landis’ An American Werewolf in London remains the gold standard for lycanthrope cinema. A shrewd and effective update of The Wolf Man for the Boomer generation, it made werewolves scary again and marked the 1980s as a golden age for sophisticated prosthetics in monster movies. And a lot of that success was achieved by Landis hiring his pal Rick Baker, a barely 30-year-old special effects makeup wunderkind, to design the beast. But as iconic as their “hound from hell” became, it was also a point of contention between the director and the makeup artist who’d win an Oscar for the work.

“I wanted it to be a biped, and I was actually hoping for something a little more on the man side as well,” Baker said in the Beware the Moon documentary about the making of the film. “I always thought it was kind of interesting, that kind of combination of animal and person. But John said, ‘No, four-legged hound from hell!’”

It is easy to see why Baker was drawn to the image of a two-legged werewolf standing upright and covered perhaps in a man’s tattered clothes. That is, after all, what werewolves had looked like onscreen since the beginning of movies.

While the earliest silent film werewolf pictures have been lost to time and obscurity, the first widely seen film about a man turning into a beast came from Universal Pictures six years before the original Wolf Man. Yep, prior to Lon Chaney Jr., there was Broadway thespian Henry Hull and his rather unlikable doomed hero in The Werewolf of London.

Released in 1935 near the tail-end of Universal’s first cycle of monster movies—it came out the same year as Bride of Frankenstein—The Werewolf of London’s eponymous beastie was designed by legendary makeup artist Jack Pierce, the same man who masterminded the looks of Karloff’s Mummy and Frankenstein Monster. He also would get to utilize his original werewolf ideas on The Wolf Man, because in 1935 the classically trained Hull demurred sitting beneath such extensive makeup. Instead, he argued, audiences would want to see the human character (and actor) still beneath the wolf design. We imagine he and Leigh Whannell might have gotten along.

As a consequence, the werewolf in Werewolf of London has more in common with Mr. Hyde in various Jekyll and Hyde flicks. Hull’s werewolf prowls the streets of London in an overcoat, scarf and hat, stalking women of the night like the spirit of Jack the Ripper returned. He even apparently retains the power of speech.

Future generations of makeup artists affectionately refer to this werewolf design as the “Elvis of Werewolves,” and even have homaged it on occasion—such as Josh Hartnett’s throwback to the more man than wolf antihero in John Logan’s underrated Penny Dreadful. Largely however, the look was supplanted and forgotten after Pierce’s improvements in ‘41.

While a staple of childhood nostalgia and Halloween decorations today, there is still something rather gnarly about Chaney in his full werewolf regalia in The Wolf Man and its various sequels. It also defined the look of a guy still in his clothes covered in so much fur that his face became completely unrecognizable. With a good actor, which on his sober days Chaney very much could be, the design might even become ferocious. There is in fact something quite wicked about the scene in the film where in appropriately dark shadows on a foggy soundstage, Chaney comes running full tilt at first Evelyn Ankers and then Claude Rains with a look of murder in his eyes. Perhaps more thrilling and amusing than scary, it’s still left an impression for a reason.

Over the following 40 years, every cinematic werewolf in one way or another was an homage, imitation, or knockoff of what Pierce and Chaney did. Some of them are quite impressive in their own right, such as another real-life hellraiser in front of and behind the camera, Oliver Reed. He experienced a much more elaborate full body fur-job in Hammer Studios’ The Curse of the Werewolf (1961). A loose adaptation of Guy Endore’s underrated novel The Werewolf of Paris, the Hammer film draws on Medieval ideas of werewolfism being passed on through the blood and the sins of the father. Yet the design in the movie is pure Hollywood, if by way of the UK’s Roy Ashton. The teeth are sharper, the face more animalistic, and the blood of his victims finally visible, but if you squint it could still just resemble Reed after a particularly bad bender.

It was probably the best 20th century upgrade on Pierce’s standard, especially when compared to the cheaper designs in movies like I Was a Teenage Werewolf (1957) and the various Paul Naschy Wolfman knockoff movies from 1970s Spain. But they, along with cartoon shows like Scooby-Doo, also made the emphasis on the Man in “Wolf Man” kitschy by the ‘80s….

The Four-Legged Hound from Hell

“A four-legged hound from hell. With blazing eyes, its wolfen features are twisted and demonic.” So reads John Landis’ screenplay for An American Werewolf in London. It’s an image he first dreamed up as a teenager in 1969 while working on Kelly’s Heroes (1970), and it’s one that never left him all the way until he forced Rick Baker to accept they’re not doing the Wolf Man anymore.

It was a shrewd choice. By the ‘80s, the bipedal werewolf was a costume that kids went trick ‘r treating in. Yet in American Werewolf, not only did Landis and Baker dream up the greatest werewolf transformation of all time, but also an enormous beast who on four legs appeared like a rabid dog with red eyes so cruel it could turn Piccadilly Circus into a slaughterhouse. It was such a tremendous achievement that the Academy finally made “Best Makeup and Hairstyling” an official category at the Oscars, just so they could award Baker for his work. It also created a boom industry for prosthetic-heavy creature features.

Ironically, it was also not the only groundbreaking werewolf movie of 1981. In fact, the werewolf transformation in The Howling is almost as good as American Werewolf’s, likely much to writer-director Joe Dante’s chagrin since he had hired Baker to design his werewolf effects during the years-long gap Baker waited for Landis to find financing for American. Ultimately, Baker awkwardly pulled out of The Howling and left his protege Rob Bottin to design that movie’s werewolves.

In truth, they are closer to a hybrid of what became Pierce and Baker’s calling cards. While still bipedal, Dante and Bottin’s werewolves stand upright at a towering seven feet. With enormous jutting snouts and long lupine ears, they are modeled after the Big Bad Wolf in Walt Disney’s classic “Three Little Pigs” cartoon from 1933. They’re every bit as terrifying to look at as Landis’ hound from hell.

Still, the hound seemed to mostly win out in the short term. The ‘80s were subsequently filled with werewolf movies that tried to emulate the elaborate transformations of both ’81 films to varying success. While some remained old-fashioned, such as the nostalgic throwback to Universal monsters in Waxwork (1988), or for that matter Baker and Landis’ work with Michael Jackson on the “Thriller” music video (which is still more of a “werecat” than wolf), more of them emulated the four-legged bestial excess of the era. This would include the first transformation in Neil Jordan’s The Company of Wolves from 1984 (the second transformation, meanwhile, saw characters turn into actual grey wolves).

And when the prosthetics craze of the ‘80s eventually died down, werewolf movies of the ‘90s and 2000s continued to owe more to American Werewolf than Wolf Man. Even the purely CGI werewolves in Stephen Sommers’ kitschy Van Helsing spend more time on four legs than two and have a big (and strangely cuddly) cartoon wolf’s head on top.

There have been throwbacks that went the other way like the aforementioned 2010s TV series, Penny Dreadful. Similarly, Jack Nicholson landed a lot closer to Henry Hull than either Lon Chaney or Landis in Mike Nichols’ Wolf (1994), but that Baker design likely had more to do with just keeping Nicholson’s moneymaker front and center.

Baker did eventually get the chance to finally do his true, fullsteam ahead tribute to the bipedal Wolf Man in a literal remake of the ’41 movie: 2010’s The Wolfman, starring Benicio del Toro. It’s not a perfect film, but Baker and del Toro’s epic monster design is a triumph, as well a tribute to Pierce’s design that is more ferocious and menacing looking in its bloody, long-clawed sophistication.

And yet, audiences rejected it then. The 2010 Wolfman flopped for a variety of other reasons too, but more than a few online critics sniffed that compared to Baker’s work on American Werewolf, the old school bipedal werewolf looked hokey. It won Baker another Oscar and today has its defenders (including this one), but the movie’s failure noticeably put a silver bullet in bipedal werewolves at a time when the creatures were more popularly seen as little better than big furry dogs in the all-CGI Twilight movie designs. Or they were turned into literal wolves, a la HBO’s attempt to cash-in on the Twilight craze with the saucier True Blood.

The Best of Both Worlds?

Based on the mixed reception of Whannell’s Wolf Man—personally I found it underwhelming, but our Joe George loved it!—it seems unlikely that the film will change opinions about the antiquated nature of the bipedal werewolf. The film might achieve its goal of making the werewolf look purely like a man dying of a strange disease, but frankly, we’d rather revel in Baker and del Toro’s update going hound-dog on London by gaslight.

Be that as it may, we think the best looking movie werewolves emulate the sophistication of Landis’ hound from hell but retain some elements of the bipedal creature. American Werewolf is the lycanthrope masterpiece of ’81, but the general monster designs in The Howling are honestly more fun. Similarly, movies that attempted to emulate both in the 21st century, such as Neil Marshall’s Dog Soldiers and the first couple of Len Wiseman-directed Underworld flicks (more so the second one where they had a decent budget) look far cooler than the CGI nonsense of either Van Helsing or Twilight.

Perhaps the best werewolves are the ones who are caught forever dead in the middle between man and beast?

The post Wolf Man: How Much ‘Man’ Do We Really Want in a Werewolf? appeared first on Den of Geek.

What's Your Reaction?