Why do some people need less sleep?

Plus, can you train yourself to sleep less? The post Why do some people need less sleep? appeared first on Popular Science.

For most of us, getting less than seven hours of sleep translates into grogginess, sluggish thinking, and an overwhelming urge to crawl back into bed. But some people wake up fresh and energized after just six hours of sleep or less. Given that sleep is essential for the body to repair and restore itself, why can some people get by with less?

Scientists have been trying to unravel the mystery of “natural short sleepers” for years, but their rarity means that there are only a handful of studies on the phenomenon.

The science says about ‘short-sleepers’

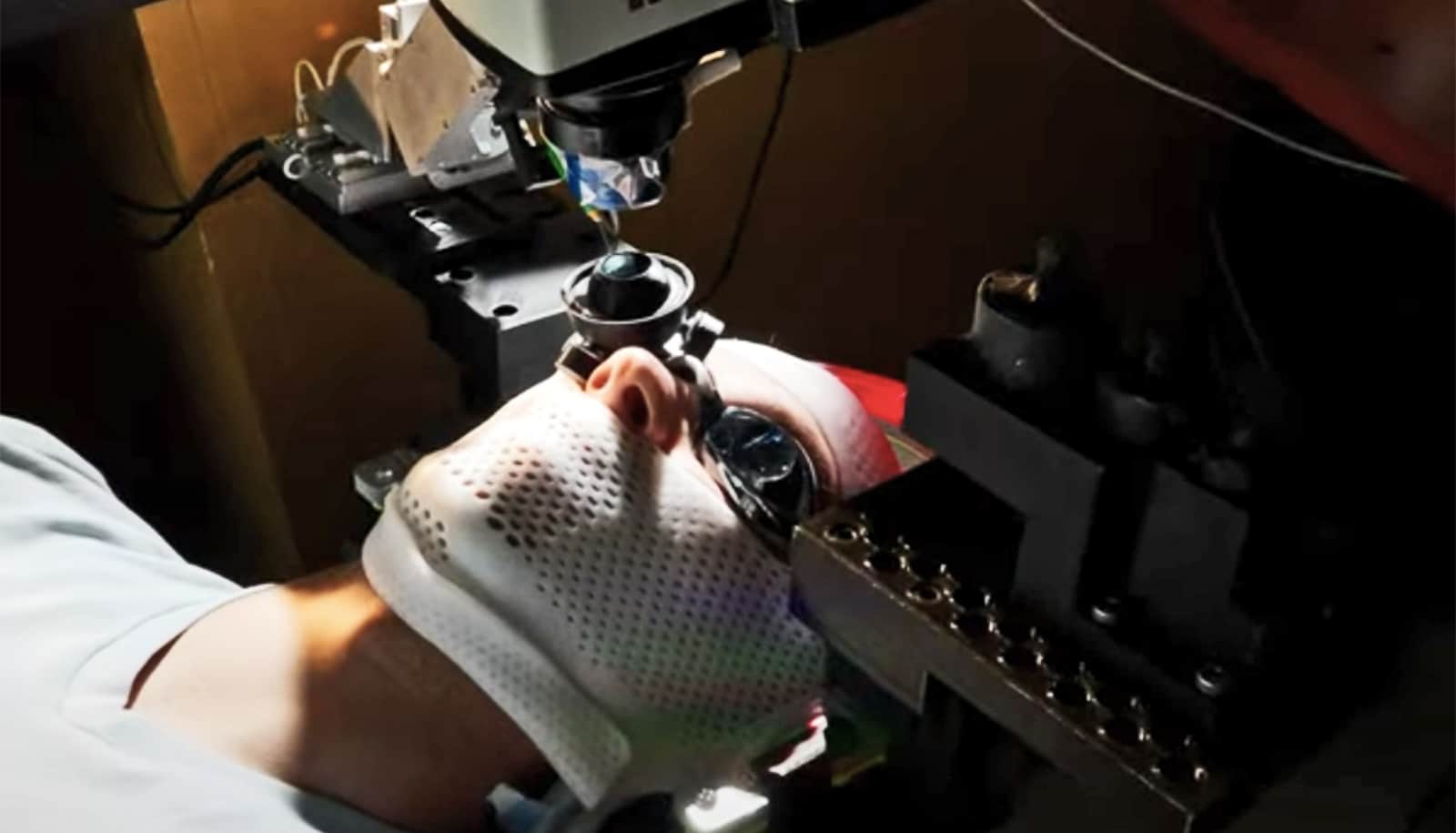

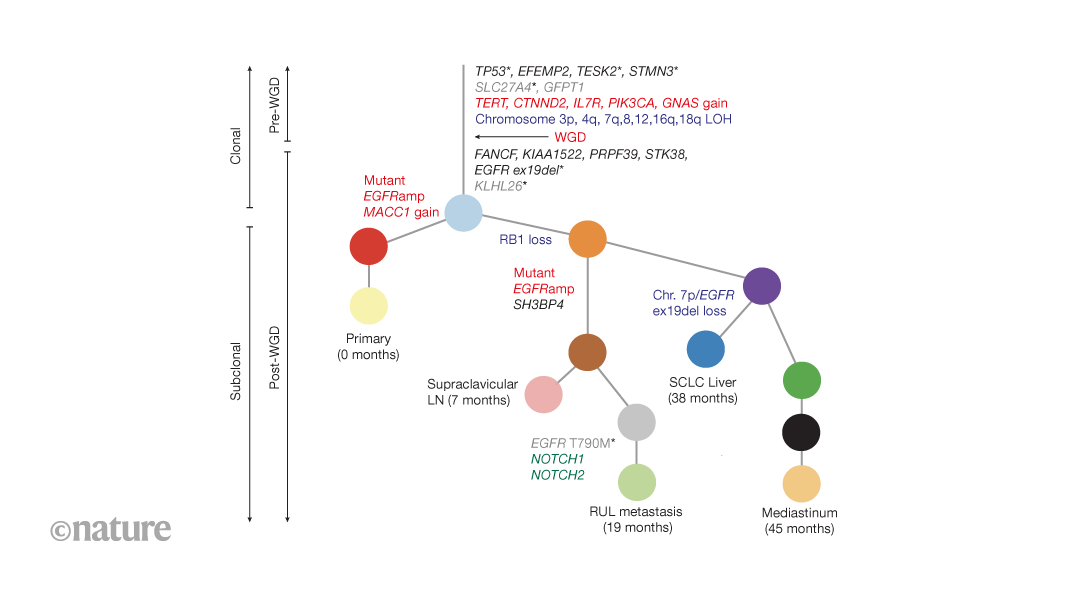

In 2009, professor of neurology Ying-Hui Fu and her team at the University of California, San Francisco discovered a mutation in the differentiated embryo chondrocyte 2 (DEC2) gene in two natural short sleepers—a mother and her adult daughter. When they engineered mice with the same mutation, these mice slept less than their normal counterparts. A follow-up study in 2018 revealed that the DEC2 gene mutation affects levels of orexin, a hormone that regulates wakefulness. Normally, the DEC2 gene shuts off orexin production in the evening and ramps it back up before dawn. But in natural short sleepers, the effect of the DEC2 gene is weaker, leading to more orexin production and more hours of wakefulness.

A decade after identifying the first “short sleep gene,” Fu’s lab discovered another one in 2019: a mutation in the adrenergic receptor beta-1 (ADRB1) gene. To understand its effects, researchers engineered mice with the same mutation—and sure enough, these mice slept less, just like human short sleepers. Further investigation showed that ADRB1 is highly active in the dorsal pons, a brainstem region that helps regulate sleep. When scientists stimulated ADRB1-expressing neurons in this area, the mice woke up instantly. Interestingly, mice with the mutation had a higher proportion of wakefulness-promoting neurons that were more easily activated. The findings suggest that the ADRB1 mutation rewires the brain for wakefulness, shortening sleep and making waking up easier.

Just weeks after identifying the ADRB1 mutation, Fu and her colleagues discovered a third “short sleep gene”—this time in a father and son who thrived on just 5.5 and 4.3 hours, respectively, of sleep per night. The newly identified mutation affects the neuropeptide S receptor 1 (NPSR1) gene, which helps regulate wakefulness. When researchers engineered mice with this mutation, the animals slept less and moved more. Furthermore, sleep-deprived mice with the NPSR1 mutation performed better in memory tests compared to sleep-deprived mice without the mutation. This suggests that the NPSR1 mutation allows natural short sleepers to maintain cognitive function and avoid the memory problems typically caused by sleep deprivation.

In 2021, Fu’s team discovered a fourth gene linked to natural short sleep. They identified two different mutations in the metabotropic glutamate receptor 1 (mGluR1) gene in two unrelated families of short sleepers. Mice carrying either mutation slept less, and further studies revealed that the gene mutations increased nerve cell activity in the brain.

So can I train myself to sleep less?

Besides genetics, the other factor that influences how much sleep a person needs is age, Elizabeth B. Klerman M.D., Ph.D., professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, told Popular Science. Generally, babies, young children, and teens need more sleep than adults to support their growth and development.

If you lead a busy life and wish you had more hours in a day, you might find yourself wondering: can I train myself to need less sleep? Probably not, is the short answer.

The quantity of sleep you need is dictated by your biology—specifically, your genes and your age. “There is no evidence that lifestyle can influence sleep need,” Klerman said.

It’s also important to distinguish true short sleepers—people who naturally function on six hours of sleep or less—from those who rely on alarm clocks, coffee, or other stimulants to get through the day. The latter “are not obtaining sufficient sleep,” Klerman said. So while you can build a tolerance to sleep deprivation, that’s not the same as actually needing less sleep.

Most of us thrive on seven to nine hours of sleep per night. Anything less will lead to sluggish thinking and slower reaction times, and can raise your risk for long-term health problems as well.

So, as much as your schedule allows, listen to your body. Trying to force yourself into short-sleeper mode is a losing battle. Quoting sleep scientist Till Roenneberg, Klerman said: “Voluntarily cutting sleep is like stopping a washing machine mid-spin cycle—why would anyone do that?”

This story is part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we answer your most outlandish, mind-burning questions, from the ordinary to the off-the-wall. Have something you’ve always wanted to know? Ask us.

The post Why do some people need less sleep? appeared first on Popular Science.