Why Contemporary Fiction Loves Analog Tech

In Catherine Airey’s new novel, a young person’s curiosity about a life lived without social media or streaming is deployed to superb effect.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

In Catherine Airey’s new novel, Confessions, a Gen Z teenage girl, Lyca, pieces together her family’s secrets in the late 2010s using decidedly 20th-century technology. She is a product of her time: She makes avatars in The Sims of herself and her crush; her mother nags her about lingering on social media instead of going out into the world. Someone like Lyca, born in the early aughts, may be just old enough to have burned songs onto a mix CD, used a phone attached to a wall, or taken an atlas on a childhood road trip—but most of their life has been defined by constant connection. (They’ve probably never had to reunite with friends in a post-concert crowd without the aid of a group chat or Find My Friends.) From this vantage point, fully understanding how life was lived in the absence of digital infrastructure can be challenging. But when Lyca begins investigating where she came from, she feels compelled to try.

First, here are three new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

- In search of the book that would save her life

- “Cloud Pantoum,” a poem for Sunday

- The ‘dark prophet’ of L.A. wasn’t dark enough

Like any digital native, Lyca turns immediately to Google. She hopes to figure out the identity of the father she’s never known, but the results are unsatisfactory. She starts to learn about family events that have long been buried—things even her mother doesn’t know—only when she finds a trove of analog heirlooms: diaries, letters, and an old point-and-click-style video game that her great-aunt helped create, which is set in the house Lyca grew up in.

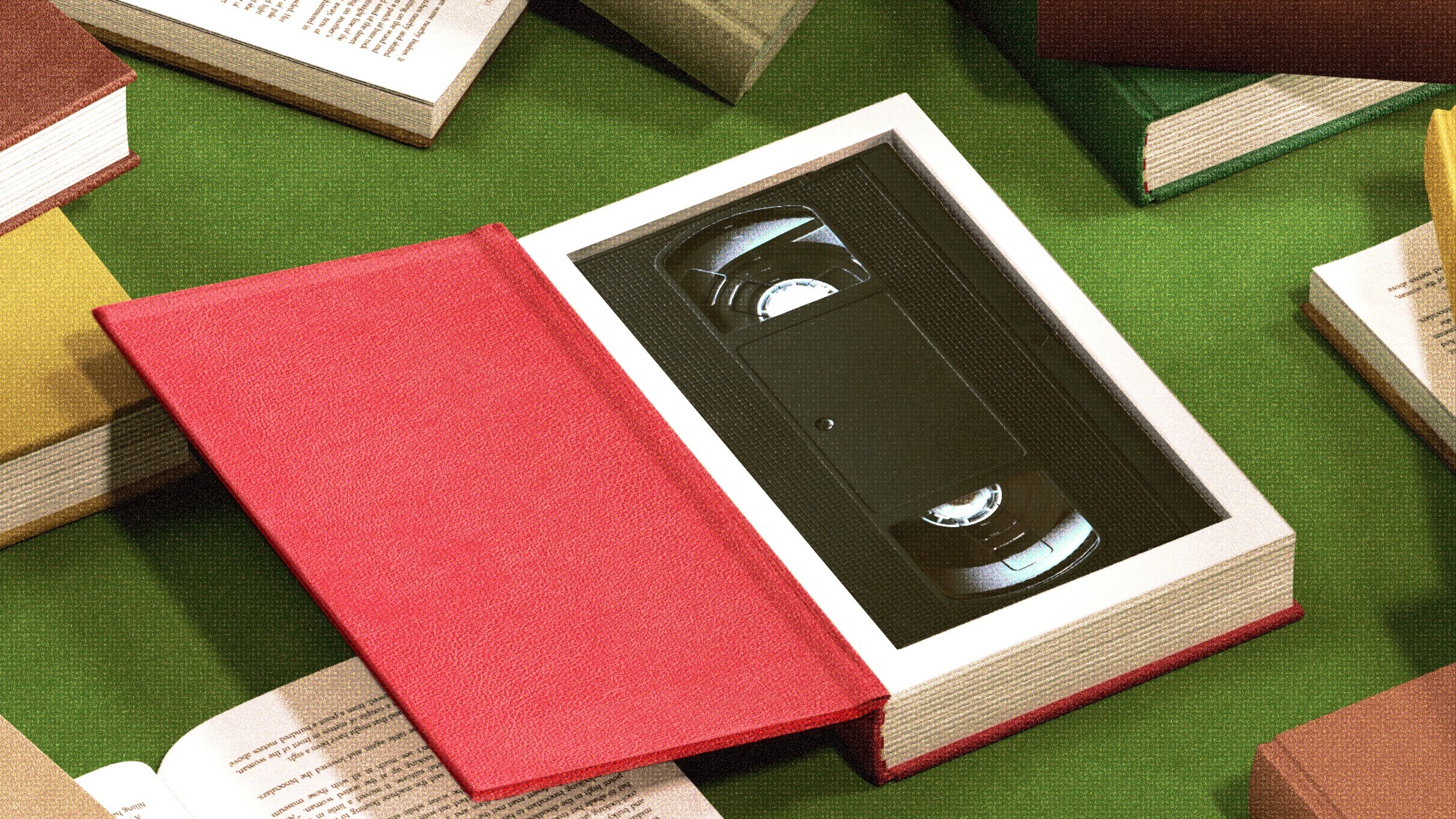

This juxtaposition—tech-savvy teen, antiquated technology—may seem unusual, but it’s actually become quite common in fiction. In the 2020s, Mark Athitakis writes in an Atlantic article this week, “vintage media have emerged as tactile objects that symbolize integrity, solve the crime, and radiate realness.” Airey’s novel is just one of a number of stories that seek some kind of lost meaning in the reels, discs, and cartridges that were ubiquitous before the turn of the 21st century. Athitakis points to the popularity of Stranger Things as a catalyst for this trope, but I imagine it also reflects a more personal longing. Lyca’s quest isn’t only about investigating her familial roots. It’s the story of a person who’s never lived without the internet in their pocket envisioning a lost past—and learning what life was like when their parents were young.

Athitakis writes that VHS tapes and film cameras offer “cozy reminders of the past” and a kind of “cultural authenticity.” I was born in the mid-1990s, so watching a videotape or developing a roll of pictures from a birthday party is associated, in my mind, with a kind of prelapsarian youth and innocence. Likewise, when I was a teenager, records, cassettes, and even CDs represented a more spontaneous, pre-algorithmic era of music discovery. My father, a lifelong music obsessive, had huge collections of physical media in our home; he’d buy whole records on the strength of their singles or word-of-mouth boosterism. My taste, by contrast, was dictated in large part by instant downloads and recommendations from Pandora and iTunes, so picking a CD from his shelf of hundreds was already an exercise in nostalgia. For Lyca, discovering and sharing old media without the interference of an algorithm is a powerful experience. She reads The Catcher in the Rye because of a quote on her crush’s Facebook; she’s fascinated and moved when he plays her Philip Glass’s score from Koyaanisqatsi.

This curiosity and slight bewilderment about a completely different kind of life—one lived without social media or streaming—is deployed to superb effect in Confessions. Few of the misunderstandings or secrets that animated the novel’s historical plot could have persisted in the modern day, and in fact, they come apart with the intervention of 2020s technology such as readily available DNA tests. Lyca has access to many things her mother, grandmother, and great-aunt didn’t; what she can’t really replicate is the texture of their experiences, which is found not in analog implements but in the elements that determined the course of their lives: chance, mystery, the ability to disappear or transform without a trace.

The Stranger Things Effect Comes for the Novel

By Mark Athitakis

A crop of stories is responding to the fakery of the digital age by embracing the realness of analog objects.

What to Read

Brother & Sister Enter the Forest, by Richard Mirabella

The pivotal car travel takes up a paltry section here, but it is impossible to look away from. Brother & Sister Enter the Forest follows two siblings as they try to find their way through a haze of trauma and estrangement. Justin is unhoused, dealing with PTSD and the physical effects of a traumatic brain injury; Willa is a nurse who makes dioramas of her and Justin’s childhood. When Justin shows up at Willa’s door asking to move in, the narration turns its gaze backwards to the events that broke them apart—a road trip that Justin took with a violent ex-boyfriend in the aftermath of a terrible crime. The trek is the book’s dark, truthful center, casting a shadow of gay shame and survivor’s guilt that takes Justin and his sister decades to see clearly. Still, even outside of those few crucial pages, the plot is infused with driving, aimless and otherwise. “I love this idea,” the siblings’ mother says to Justin. “Taking someone out in a car. You’re trapped. So we can really have a good talk without you running away like you always do.” — Emma Copley Eisenberg

From our list: Eight books to take with you on a road trip

Out Next Week

.png)

![‘Companion’ Ending Breakdown: Director Drew Hancock Tells All About the Film’s Showdown and Potential Sequel: ‘That’s the Future I Want for [Spoiler]’](https://variety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/MCDCOMP_WB028.jpg?#)