Truth Social: On the Still-Human Films of Sohrab Hura

The Lost Head and the Bird (Sohrab Hura, 2018).“We are excited to announce insulin is free now.” At first glance, this November 2022 Twitter post from @EliLillyandCo appeared to be a legitimate announcement from the pharmaceutical company; the account’s profile featured an icon of Eli Lilly and Company’s logo and a blue check mark that, until the previous day, signified the account had been formally verified by the platform’s dedicated staff. But in the hands of new owner Elon Musk, who completed his acquisition of the platform two weeks earlier, Twitter’s verification process underwent significant modification. Suddenly, verification was available to anyone with an authenticated phone number and a willingness to pay $8 a month for the platform’s Premium plan. Twitter, soon to be rebranded as X, inevitably descended into chaos, rife with impersonators and misinformation. Eli Lilly’s stock share price fell by 4.37 percent in one day. What, above all, this episode seemed to signal was the breakdown of institutional responsibility. Prioritizing revenue over accountability, Twitter abandoned any pretense that it would be an arbiter of authenticity; Meta recently followed suit, announcing on January 7 of this year that it would be ditching its fact-checkers in favor of a crowdsourced system of community notes. In our era of “post-truth” politics, images and videos have become laden with new economies of meaning, not all of them based in fact. Social media platforms, as we have seen time and time again, are not neutral mediators but actively influence the reception of content—whether by amplifying certain narratives through algorithmic promotion, stripping or adding context via content labels, or allowing virality to determine credibility.You’ll find a similar line of interest in the crisp, hyper-saturated pictures of the Indian photographer and filmmaker Sohrab Hura, whose recent projects take up a study of synthetic images and how they are distributed. He began working this way as a direct response to the 2004 Indian election, in which the Bharatiya Janata Party’s ultranationalism and “India Shining” slogan aimed to project an image of an economically strong and empowered country—one far from the reality lived by many Indians, especially those in rural areas. Returning to power in 2014 with Narendra Modi as prime minister, the BJP undertook an even more aggressive campaign of propaganda and distortion. V. K. Singh, a cabinet minister, has referred to journalists as “presstitutes.” Modi claims to have once worked as a humble tea seller on a railway platform, though a 2015 Right to Information query cast doubt on his story. Campaign video for Manoj Tiwari, a BJP candidate for parliament, appears to show him speaking English and Haryanvi, the latter a direct appeal to Delhi’s large population of migrant workers. When it was revealed that the original speech was in Hindi, and that the other versions were AI-assisted deepfakes, the BJP dismissed the episode as an experiment.Sohrab Hura, Remains of the day, 2024. Soft pastel on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata and Mumbai. Surreal times call for surrealist art. Mother, now on view at MoMA PS1 in New York, is the first US survey of Hura’s work. It orchestrates a kaleidoscope of images and sounds, plunging viewers into a maelstrom of ambiguity where truth is indistinguishable from fiction. Single-channel videos flash and whir, suffused with a palpable anxiety. His lurid pastel illustrations and paintings in gouache and acrylics show some fidelity to photography, composed like snapshots or selfies. Together, these varied forms of practice seem to ask if some mediums are more inclined to capture reality than others. In Mother, we find not just Hura’s inquiry into the self, but into his motherland.Things Felt but Not Quite Expressed, a collection of Hura’s illustrations with sardonically self-referential titles, was created between 2022 and 2024, when he was experiencing a disconnect from the fixed nature of photography, moving from image to illustration to capture the idiosyncrasies of quotidian life in an increasingly polarized world. A meme of a French bulldog captioned “Men over 35 in skinny jeans”; impressionistic lashings of bright color; a portrait of a refugee Palestinian couple lying idly in a Syrian field—the art of Things Felt is by turns dreamy, hilarious, and deeply moving. It also speaks to Hura’s recent efforts to consolidate emotional truth into his images. Photographic glitches allow Hura to explore the manipulation and distortion of meaning in a world increasingly dominated by algorithm-driven images. A glitch could be as simple as the warping of a scanned photo, or the telltale signs of some crude Photoshopping. (Think of the hysteria that Princess Catherine’s doctored Mother’s Day photo caused earlier this year and the very meme-able apology that followed: “Like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editi

The Lost Head and the Bird (Sohrab Hura, 2018).

“We are excited to announce insulin is free now.” At first glance, this November 2022 Twitter post from @EliLillyandCo appeared to be a legitimate announcement from the pharmaceutical company; the account’s profile featured an icon of Eli Lilly and Company’s logo and a blue check mark that, until the previous day, signified the account had been formally verified by the platform’s dedicated staff. But in the hands of new owner Elon Musk, who completed his acquisition of the platform two weeks earlier, Twitter’s verification process underwent significant modification. Suddenly, verification was available to anyone with an authenticated phone number and a willingness to pay $8 a month for the platform’s Premium plan. Twitter, soon to be rebranded as X, inevitably descended into chaos, rife with impersonators and misinformation. Eli Lilly’s stock share price fell by 4.37 percent in one day. What, above all, this episode seemed to signal was the breakdown of institutional responsibility. Prioritizing revenue over accountability, Twitter abandoned any pretense that it would be an arbiter of authenticity; Meta recently followed suit, announcing on January 7 of this year that it would be ditching its fact-checkers in favor of a crowdsourced system of community notes. In our era of “post-truth” politics, images and videos have become laden with new economies of meaning, not all of them based in fact. Social media platforms, as we have seen time and time again, are not neutral mediators but actively influence the reception of content—whether by amplifying certain narratives through algorithmic promotion, stripping or adding context via content labels, or allowing virality to determine credibility.

You’ll find a similar line of interest in the crisp, hyper-saturated pictures of the Indian photographer and filmmaker Sohrab Hura, whose recent projects take up a study of synthetic images and how they are distributed. He began working this way as a direct response to the 2004 Indian election, in which the Bharatiya Janata Party’s ultranationalism and “India Shining” slogan aimed to project an image of an economically strong and empowered country—one far from the reality lived by many Indians, especially those in rural areas. Returning to power in 2014 with Narendra Modi as prime minister, the BJP undertook an even more aggressive campaign of propaganda and distortion. V. K. Singh, a cabinet minister, has referred to journalists as “presstitutes.” Modi claims to have once worked as a humble tea seller on a railway platform, though a 2015 Right to Information query cast doubt on his story. Campaign video for Manoj Tiwari, a BJP candidate for parliament, appears to show him speaking English and Haryanvi, the latter a direct appeal to Delhi’s large population of migrant workers. When it was revealed that the original speech was in Hindi, and that the other versions were AI-assisted deepfakes, the BJP dismissed the episode as an experiment.

Sohrab Hura, Remains of the day, 2024. Soft pastel on paper. Courtesy of the artist and Experimenter, Kolkata and Mumbai.

Surreal times call for surrealist art. Mother, now on view at MoMA PS1 in New York, is the first US survey of Hura’s work. It orchestrates a kaleidoscope of images and sounds, plunging viewers into a maelstrom of ambiguity where truth is indistinguishable from fiction. Single-channel videos flash and whir, suffused with a palpable anxiety. His lurid pastel illustrations and paintings in gouache and acrylics show some fidelity to photography, composed like snapshots or selfies. Together, these varied forms of practice seem to ask if some mediums are more inclined to capture reality than others. In Mother, we find not just Hura’s inquiry into the self, but into his motherland.

Things Felt but Not Quite Expressed, a collection of Hura’s illustrations with sardonically self-referential titles, was created between 2022 and 2024, when he was experiencing a disconnect from the fixed nature of photography, moving from image to illustration to capture the idiosyncrasies of quotidian life in an increasingly polarized world. A meme of a French bulldog captioned “Men over 35 in skinny jeans”; impressionistic lashings of bright color; a portrait of a refugee Palestinian couple lying idly in a Syrian field—the art of Things Felt is by turns dreamy, hilarious, and deeply moving. It also speaks to Hura’s recent efforts to consolidate emotional truth into his images.

Photographic glitches allow Hura to explore the manipulation and distortion of meaning in a world increasingly dominated by algorithm-driven images. A glitch could be as simple as the warping of a scanned photo, or the telltale signs of some crude Photoshopping. (Think of the hysteria that Princess Catherine’s doctored Mother’s Day photo caused earlier this year and the very meme-able apology that followed: “Like many amateur photographers, I do occasionally experiment with editing.”) Hura views these glitches as “fault lines of doubt,” spaces that allow new layers of understanding to emerge.1 They “have this ability to give us a sense of the real in an increasingly fake world," he explains, pointing to the onslaught of edited images we are exposed to daily.2 As AI and algorithms generate more viral content, he believes the future of photography and film lies in these mistakes and accidents, indissoluble from human nature.

The Lost Head and the Bird (Sohrab Hura, 2018).

Hura works to draw out that fluidity in his films, too. In The Lost Head and the Bird (2018), the artist induces sensory overload through a rapid-fire montage of found footage—images of Bollywood stars, right-wing propaganda, and bloody violence—all interleaved with Hura’s own photographs. The intensity of this visual barrage is amplified by a frenetic soundtrack by Hannes d’Hoine and Sjoerd Bruil, which disrupts our ability to accurately interpret what we see. The film takes its name from the surreal one-page story and photo series published in Hura’s book The Coast (2019), which introduces Madhu, a pitiful woman whose head was stolen by a jealous ex-lover as her pet bird escaped its cage. In the film, a fortune teller sells Madhu a crow, having convinced her that it’s a parrot with a bad cough. The final character in the story, Hura explains, is himself: the photographer, complicit in this violence and deception. In implicating himself, he also implicates the viewer in this voyeurism, claiming that “both of us are helping circulate these images,” blurring the lines between participant and observer.3

Watching The Lost Head is a borderline hallucinatory experience. An iteration of the project for MoMA in 2021 featured twelve versions of the film accompanied by unnerving short stories, each a slight variation of the one that came before. By subtly changing our understanding of Madhu in each retelling, Hura plays with our instinct to trust photographic images and escalates the viewer’s confusion. Confounding any notion of objectivity, he evinces how meaning can be warped not just by manipulating images but also through the sequencing of information.

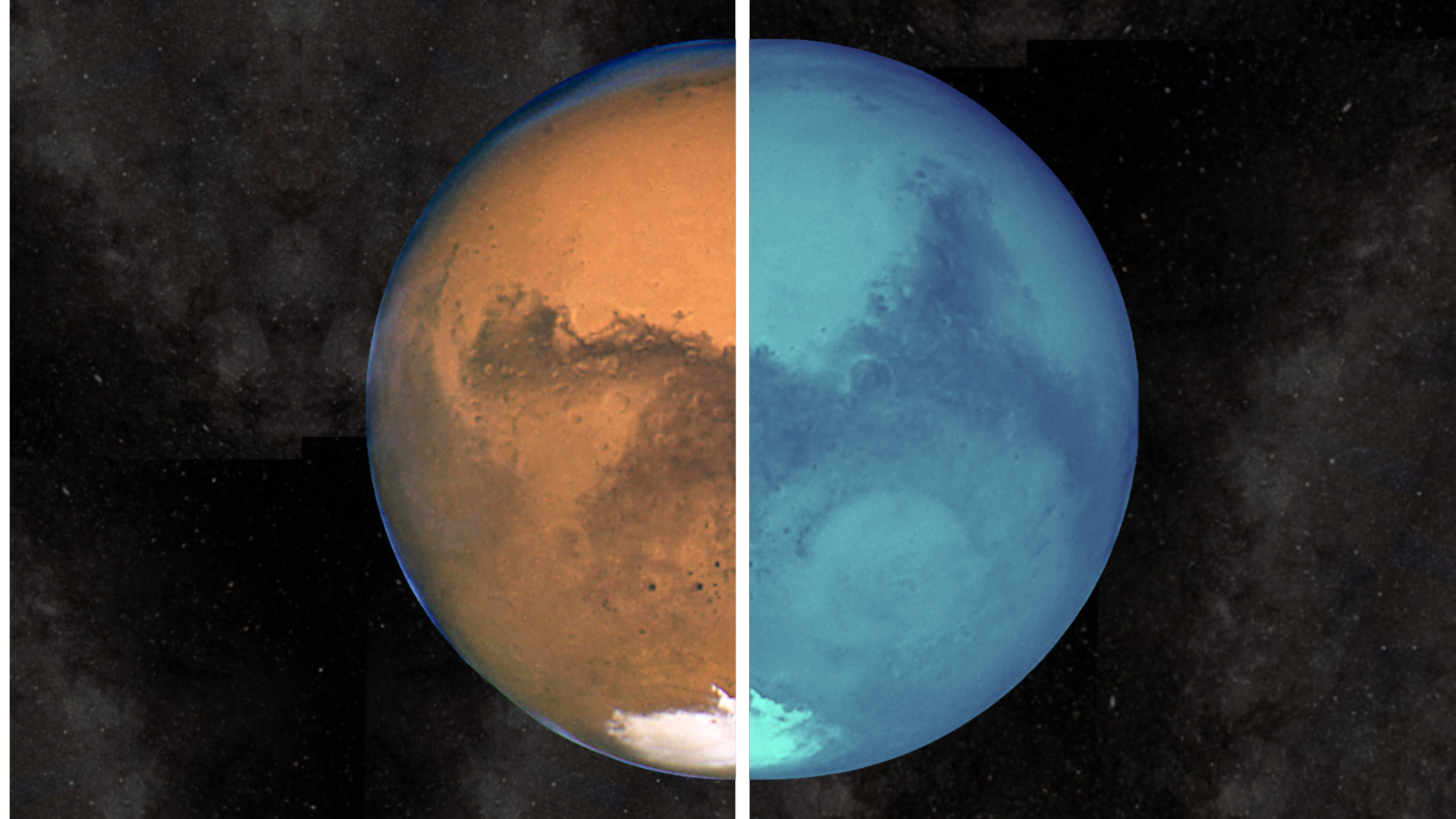

The Coast (Sohrab Hura, 2020).

Using footage and stills taken after religious celebrations in a coastal village in Tamil Nadu, The Coast (2020) retains this slightly surreal quality, though its narrative is far more tightly controlled. The project began as a photobook in 2018, and the film develops the original concept by embracing a plurality of forms, using the margin between land and water as a point of release to explore the undercurrents of religious, sexual, and caste-related violence along India’s coastline. The intimate footage transitions from sacred communal fervor to quiet, unsettling moments of post-festival reflection, in which bodies and spaces take on an otherworldly quality. Once again, Hura manipulates context by covertly adding and removing details to blur lines between reality and artifice; his harsh, unforgiving flash creates visuals that mirror the fragmented, fetishistic language of social media images. In The Coast, this litany is brought to life by shots of India’s shoreline, deployed throughout Hura’s work as a metaphor for a society on the brink of collapse. But here, the sea also manifests as a site of religious ritual as demonic masquerades, bloodletting, scenes of destitution, deformity, and anguish unfold. At first, the lapping waves seethe with libidinal energy, then the film gradually transitions to more serene images of darkened figures diving into the ocean, submitting to its primal force. This climactic moment, when the sea collides with grainy, ecstatic bodies, offers them release from artifice in their heightened psychospiritual state. As Hura puts it, “nothing is definite, everything is raw and overwhelming.”

While The Lost Head islaced with references to Ganesha, The Coast affects allusions to religion more literally as festivalgoers masquerade as different deities, entering a trancelike frenzy as their bodies hit the water, which washes away their face paint. Hura explains that in India, “perhaps more so than anywhere else, fiction, stories … live longer than factual stories. They are allegories that people return to, constants in the ongoing turbulence of politics, religion, and caste.”4 This idea of enduring allegories seems especially pertinent in a time when religious narratives are increasingly distorted and weaponized. The BJP, for example, has made incendiary anti-Muslim rhetoric integral to its political strategy. During the 2024 election, the party explicitly framed themselves as defenders of Hindu interests, portraying Muslims as an external threat. In May 2024, civil and corporate watchdog groups submitted fake advertisements to Meta as a test of their filtering mechanisms: one proclaimed that “Hindu blood is spilling, these invaders must be burned,” while another called for the execution of a rival political leader. Both were approved to appear on Facebook and Instagram.

Pati (Sohrab Hura, 2010).

Given Hura’s deliberate shift away from aesthetic objectivity in recent years, it’s interesting that his earlier work is marked by an earnest confidence in film’s potential for truth-telling. His first film, Pati (2010), is an eleven-minute black-and-white documentary featuring barren landscapes—the aftermath of deforestation and deprivation—in the village of Pati, Madhya Pradesh. Collating photos taken in 2005, the projectchronicles the final push from activists, students, academics, journalists, and artists campaigning for the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act: a landmark bill that, once implemented, guaranteed 100 days per year of minimum-wage employment for all adult members of a rural household. One particularly moving scene shows children working at a construction site. “Life is not the easiest for [them],” says Hura in voice-over. “There is no respite for anyone over here, and any hand is a helping hand, no matter how small it is.”

Pati’s framing of children’s resilience here shares an edifying quality with Francis Alÿs’s Children’s Games video series (1999–), which also looks to make sense of injustice through the eyes of the innocent. While Alÿs films with an anthropological closeness, Hura instead draws attention to his role as the “idiot photographer”: a spectator all too aware of his role in the complicity and cruelty required to make such images.5 Yet his self-awareness doesn’t necessarily absolve him; by foregrounding his own position, Hura risks turning ethical scrutiny into an aesthetic device, one that allows the film to acknowledge its own voyeurism without disrupting it. In this way, Pati becomes complicit in the very structures of image-making it seeks to expose.

Bittersweet (Sohrab Hura, 2019).

In an earlier short, Bittersweet (2019), Hura initially resisted this impulse to question the ethical place of the photographer. Documenting Hura’s life over ten years, the film focuses on his mother—diagnosed with acute paranoid schizophrenia when he was seventeen—and her relationship with her dog, Elsa. Here, his discomfort was more personal, shaped by his dual role as both son and photographer. Looking back on the film in 2019, he explained his early reluctance to share this work:

I didn’t want to feel vulnerable. I didn’t want others to look at her in pity or shock. At the time I had thought that I was being protective of her, but I soon realized that I was actually being protective of myself. How they might have looked at my mother would also define how they looked at me and that scared me. But how could I continue to parachute into someone else’s life and photograph another mother when I couldn’t photograph my own? I had started to feel sure that I needed to turn the camera on myself. I felt that I needed to earn my right to photograph someone else’s life by first putting my own out there with nothing held back.6

In that sense, Bittersweet functions like an eerie family album: grainy, overexposed photos overlaid with discordant sounds, produced by transforming light exposure readings of the scanned photos into sound frequencies. Like synaptic connections, the images weave together fragments of his mother’s fractured reality, allowing the viewer the impression of witnessing a schizophrenic episode through intrusive snapshots. Sometimes she smokes, looking melancholic; sometimes she lies in bed, smiling with Elsa. While Bittersweet remains Hura’s most personal—certainly his most vulnerable—work to date, it represents a significant shift in his engagement with reality. As he questions the boundaries between personal exposure and public consumption, Hura moves beyond mere documentation, instead drawing the viewer into his intimate, subjective experience and the complex social processes through which images are consumed and interpreted.

Today, Hura's work takes on a new urgency. Meta plans to populate its platforms with AI-generated users; there has been a surge in harassment, hate speech, and misinformation since Musk’s takeover of X. (And that’s without accounting for the platform’s role in aiding Trump secure the US Presidency, or Musk’s attempts to wade into British politics.) None of this is new thematic territory for Hura, though, who has spoken about the political ramifications of digitally altered images for years. “With algorithms and AI now making most of these viral videos and images—and this is only going to get more prolific and perverse—I feel the future of photography lies in its glitches,” he observes. “As photographers, we will make mistakes, and accidents will happen, and these will help us remember that we are still human.”7 Hura’s art toys with the manipulability of images and their contexts, challenging viewers to chart the hidden codes and meanings embedded within them. In his films, we find a madness that asks us to suspend our belief while drawing us in deeper: we find a world in disarray, much like our own.

- Sohrab Hura, “Images Are Masks,” e-flux Journal. ↩

- Hura, “Images Are Masks.” ↩

- Stuart Comer, “Sohrab Hura’s The Lost Head and the Bird,” The Museum of Modern Art, May 12, 2021. ↩

- Sean O’Hagan, “Fights, festivals, fear: Sohrab Hura's angst-ridden India,” The Guardian, August 5, 2019. ↩

- Skye Arundhati Thomas, “Sohrab Hura – interview: ‘The only thing I can take responsibility for is my own relationship with the world,’” Studio International, August 28, 2019. ↩

- Sohrab Hura, “Sohrab Hura on his Dilemmas Photographing the Marginalized,” Magnum Photos, November 16, 2018. ↩

- Arundhati Thomas, “Sohrab Hura.” ↩