In Print | Growing Pains: Hollywood’s Digital De-aging

This piece was originally published in Issue 6 of Notebook magazine as part of a broader exploration of the cinema of youth. The magazine is available via direct subscription or in select stores around the world.1. HOLLYWOOD’S NEW FACESOver in Hollywood, film stars are aging. The perceived failure of the industry to produce a new roster of movie stars that match up to their celebrity predecessors, coupled with a certain unwillingness on the part of producers to back untested star-powered features within the “new economic realities of the post-streaming-war era,” has led to the same A-listers who emerged in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s—Tom Cruise (62), Tom Hanks (68), Meryl Streep (74), Samuel L. Jackson (75), and Robert De Niro (81)—still being called upon to carry the fortunes of the latest blockbuster.1 As recently as May 2024, the Hollywood Reporter wrote: “Studio slates are undoubtedly still dominated by franchise installments, but executives are looking for star vehicles,” noting the versatility of a crop of new young stars like Glen Powell, Zendaya, Timothée Chalamet, Jenna Ortega, and Sydney Sweeney, who are “less formulaic than their predecessors of just a decade ago.”2 The emergence of younger performers climbing the Hollywood ladder goes beyond signaling possible industry exhaustion with multipart and multimedia narratives; it has begun to correct what had been viewed as the progressive “graying” of popular film. Since the early 2000s, the surge in a cinema that features older, more mature protagonists and celebrates the vicissitudes of aging has both exploited Hollywood’s growing collection of aging movie stars and catered to the most dominant audience demographic within the US entertainment market. A glance at Hollywood history illustrates how it has always satisfied the taste cultures of the post-warbaby boomgeneration. Baby boomers’ sizeable impact on the generic trajectory of modern Hollywood can easily be plotted in the rise of the “teenpic” or juvenile delinquent films in the 1950s and 1960s when this demographic were youthful teenagers; the 1980s family films of Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, and Chris Columbus as they assumed the role of parents; and finally the “more adult-oriented, or adult-fixated, movies between the late 1980s and early 1990s” that mirrored the growing maturation of the boomer generation through their sympathetic depiction of the reflections and experiences of older protagonists.3 But now well into retirement age, boomers’ cultural power has again become a lightning rod for the shifting conventions of Hollywood genre cinema. In The Silvering Screen, academic Sally Chivers argued that following the millennial celebrations of “time passing,” aging transformed into a fundamental storytelling component, with multiple films featuring aging “not just as a background concern to make youthful plots more virile and fascinating, but as a central premise.”4 It is within this intensified industrial moment that the stakes of digital de-aging as both a pervasive visual effects technique within commercial film production and a reflexive interrogation of the politics of aging might now be properly, and emphatically, understood.X-Men: The Last Stand (Brett Ratner, 2006).2. THE ARRIVAL OF DIGITAL DE-AGING TECHNOLOGIESThe rapid acceleration of computer-generated imagery (CGI) over the last three decades has cultivated a range of convincing digital figurations and facsimiles that have seemed to confirm the initial fears around the displacement of the human performer by the digital proxy, as predicted by the Hollywood trade press during the popularization of computer graphics at the turn of the millennium. Indeed, the first wave of Hollywood cyberstars was produced against the backdrop of early-2000s anxieties about the industry’s growing reliance upon synthespians and virtual actors, fueled largely by the arrival of motion-capture technologies and the substitution of the human performer by encroaching digital VFX. However, given Hollywood’s notorious pursuit of the spectacle of youth, it comes as little surprise that the industry has spent nearly twenty years simultaneously interrogating the possibilities of such digital surrogates, virtual clones, and computer-generated avatars to rework aging stars as younger models. Since the de-aged appearances of Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen (then both in their sixties) in the opening sequence of X-Men: The Last Stand (Brett Ratner, 2006), alongside the pioneering backwards aging effects of Brad Pitt produced for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (David Fincher, 2008), multiple Hollywood stars have convincingly and willingly appeared as their younger selves thanks to advances in three-dimensional modeling, digital compositing, facial scanning, and face replacement technology. Transforming the work of an industry that had previously relied upon practical effects (prosthetics, painted latex, hairpieces, sculpted foam) to craft the naturalistic i

This piece was originally published in Issue 6 of Notebook magazine as part of a broader exploration of the cinema of youth. The magazine is available via direct subscription or in select stores around the world.

1. HOLLYWOOD’S NEW FACES

Over in Hollywood, film stars are aging. The perceived failure of the industry to produce a new roster of movie stars that match up to their celebrity predecessors, coupled with a certain unwillingness on the part of producers to back untested star-powered features within the “new economic realities of the post-streaming-war era,” has led to the same A-listers who emerged in the 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s—Tom Cruise (62), Tom Hanks (68), Meryl Streep (74), Samuel L. Jackson (75), and Robert De Niro (81)—still being called upon to carry the fortunes of the latest blockbuster.1 As recently as May 2024, the Hollywood Reporter wrote: “Studio slates are undoubtedly still dominated by franchise installments, but executives are looking for star vehicles,” noting the versatility of a crop of new young stars like Glen Powell, Zendaya, Timothée Chalamet, Jenna Ortega, and Sydney Sweeney, who are “less formulaic than their predecessors of just a decade ago.”2 The emergence of younger performers climbing the Hollywood ladder goes beyond signaling possible industry exhaustion with multipart and multimedia narratives; it has begun to correct what had been viewed as the progressive “graying” of popular film. Since the early 2000s, the surge in a cinema that features older, more mature protagonists and celebrates the vicissitudes of aging has both exploited Hollywood’s growing collection of aging movie stars and catered to the most dominant audience demographic within the US entertainment market.

A glance at Hollywood history illustrates how it has always satisfied the taste cultures of the post-warbaby boomgeneration. Baby boomers’ sizeable impact on the generic trajectory of modern Hollywood can easily be plotted in the rise of the “teenpic” or juvenile delinquent films in the 1950s and 1960s when this demographic were youthful teenagers; the 1980s family films of Steven Spielberg, Robert Zemeckis, and Chris Columbus as they assumed the role of parents; and finally the “more adult-oriented, or adult-fixated, movies between the late 1980s and early 1990s” that mirrored the growing maturation of the boomer generation through their sympathetic depiction of the reflections and experiences of older protagonists.3 But now well into retirement age, boomers’ cultural power has again become a lightning rod for the shifting conventions of Hollywood genre cinema. In The Silvering Screen, academic Sally Chivers argued that following the millennial celebrations of “time passing,” aging transformed into a fundamental storytelling component, with multiple films featuring aging “not just as a background concern to make youthful plots more virile and fascinating, but as a central premise.”4 It is within this intensified industrial moment that the stakes of digital de-aging as both a pervasive visual effects technique within commercial film production and a reflexive interrogation of the politics of aging might now be properly, and emphatically, understood.

X-Men: The Last Stand (Brett Ratner, 2006).

2. THE ARRIVAL OF DIGITAL DE-AGING TECHNOLOGIES

The rapid acceleration of computer-generated imagery (CGI) over the last three decades has cultivated a range of convincing digital figurations and facsimiles that have seemed to confirm the initial fears around the displacement of the human performer by the digital proxy, as predicted by the Hollywood trade press during the popularization of computer graphics at the turn of the millennium. Indeed, the first wave of Hollywood cyberstars was produced against the backdrop of early-2000s anxieties about the industry’s growing reliance upon synthespians and virtual actors, fueled largely by the arrival of motion-capture technologies and the substitution of the human performer by encroaching digital VFX. However, given Hollywood’s notorious pursuit of the spectacle of youth, it comes as little surprise that the industry has spent nearly twenty years simultaneously interrogating the possibilities of such digital surrogates, virtual clones, and computer-generated avatars to rework aging stars as younger models.

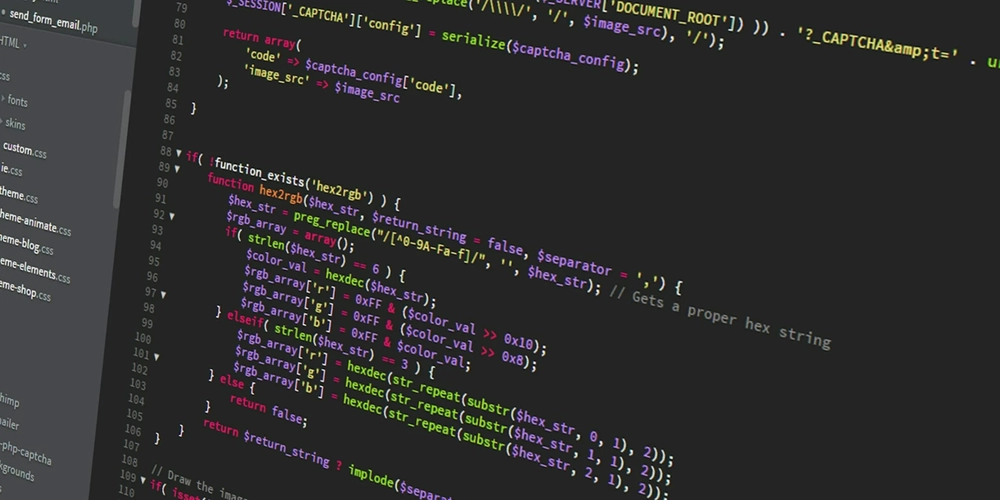

Since the de-aged appearances of Patrick Stewart and Ian McKellen (then both in their sixties) in the opening sequence of X-Men: The Last Stand (Brett Ratner, 2006), alongside the pioneering backwards aging effects of Brad Pitt produced for The Curious Case of Benjamin Button (David Fincher, 2008), multiple Hollywood stars have convincingly and willingly appeared as their younger selves thanks to advances in three-dimensional modeling, digital compositing, facial scanning, and face replacement technology. Transforming the work of an industry that had previously relied upon practical effects (prosthetics, painted latex, hairpieces, sculpted foam) to craft the naturalistic image of youth, digital de-aging has provided filmmakers with a new set of highly photorealistic age reversal techniques. The computerized re-sculpting of face shapes and the recoloration of hair; the retouching of skin complexion via digital painting and grading techniques; cleanup and contour on the forehead and around the eyes; raising the height of cheekbones; and the resizing of ears and noses are just some of the age-reversal techniques that comprise what Los Angeles-based studio Lola VFX first advertised as its innovative suite of “digital cosmetic enhancements.”5 Writing in 2006, journalist Barbara Robertson described Lola’s ground-breaking development of “digital skin grafting” for X-Men: The Last Stand, a process that involved the smoothing-out and tightening of age lines and wrinkles while maintaining both Stewart’s and McKellen’s “expressiveness and performance, as well as such skin details as pores, lines, and subtle wrinkles” even as it de-aged the actors by several decades.6

In the years since de-aging’s Hollywood debut, Lola has emerged as a leading specialist in de-aging procedures for big-screen productions, though the sophisticated techniques developed by rival companies such as Industrial Light and Magic (ILM), Framestore, Digital Domain, and Peter Jackson’s Wētā FX have helped crown the virtual recreation of youth as contemporary Hollywood’s “VFX Trick Du Jour,” with its well-publicized potential for painless nips and tucks that refine the altogether more invisible digital beauty effects common to the fashion and advertising industries.7 In fact, Lola’s work on both X-Men: The Last Stand and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button—as the first company to offer such post-production techniques—provided an early set of experiments in the manipulation of footage already shot in-camera. But it also gave fresh visibility to what was otherwise labeled as digital makeup or beauty work that typically involved secretive tweaks to a performer’s face in the spirit of imperceptible rejuvenation.

Whether making young an original A-list star’s body or grafting a digital facsimile of their newly youthened physiognomy onto a younger performance double to complete the illusion, digital de-aging as an increasingly sophisticated technology of representation and falsification has become more than ready for its close-up. Describing the de-aging of Tony Stark (Robert Downey Jr.) for the superhero blockbuster Captain America: Civil War (Anthony Russo and Joe Russo, 2016), Lola’s visual effects supervisor Trent Claus explains some of the almost undetectable de-aging adjustments made to Downey Jr.’s skin and complexion through the familiar language of anti-aging, with particular emphasis on the “increase in the way light reflects off the sheen of the skin, a reduction in the appearance of tiny blood vessels under the surface of some parts of the face, or more blood flow in the cheeks giving them that familiar youthful ‘glow.’”8 More recently, visual effects artists at ILM, Robert Weaver and Andrew Whitehurst, have discussed the company’s development of its own proprietary software systems that provide “accurate references for pore-level detail” and support the complex rendering of moving muscles to capture an authentic “facial performance.”9 However, the rapid expansion of digital de-aging processes has been shown to hold implications for the verbal as well as the visual. A vital (if often overlooked) component of Hollywood’s virtual recreation of youth has been the application of archival voice recordings, synthesized speech technology, and machine learning to seamlessly “cast” popular stars as their younger selves. The digitized re-conjuring of youthful star sound has been facilitated by developments in sound recording technologies and audio-mixing techniques, and further supported by the emergence of specialized companies involved in the kinds of voice-altering technologies and modulated voice cloning that accompany Hollywood’s pristine de-aged visuals.10 But in avoiding any requirement for secondary vocal impersonations and relying instead on both the manipulation of existing vocal tracks and the fabrication of entirely new ones, the newfound malleability afforded by vocal de-aging techniques provides yet another potential barrier for developing actors who might otherwise have performed in such younger roles.

The Expendables 3 (Patrick Hughes, 2014).

3. THE POLITICS OF AGING

De-aging, as an increasingly accepted practical tool within the armory of Hollywood VFX, provides a heavily computerized representation of resurgence and authority for an aging boomer market used to seeing the stars of their youth march headlong toward the twilight of their careers. The scope of digital touch-ups and restorative “youthening” procedures now available in this reflexive process of de-aging perhaps marks the inevitable culmination of a cinema and its stars: with nowhere else to go now but back. The rise of so-called “geri-action” cinema, for example—action-oriented features that hinge on the violent spectacle of aged masculinity—seemed to mark Hollywood’s final concession to the cultural loss of youth felt by its lucrative boomer audience. This was a cinema epitomized by the aging ensembles of Sylvester Stallone’s The Expendables series (2010–23), the sequels and spin-offs to the same actor’s Rocky (1976–) and Rambo (1982–2019) franchises, and newer entries in the Die Hard (1988–2013) and Indiana Jones (1981–2023) series led by men (Bruce Willis, Harrison Ford) aged fifty and over. Hollywood had become a newly viable place where the (typically male) aged star body could still shine one last time, and where there was business potential in presenting actors not afraid to look and sound their age. Dramas like The Bucket List (Rob Reiner, 2007) and Gran Torino (Clint Eastwood, 2008); the Nancy Meyers-directed romantic comedies Something’s Gotta Give (2003) and The Intern (2015); sports features like The Wrestler (Darren Aronofsky, 2008) and Trouble with the Curve (Robert Lorenz, 2012); crime films Going in Style (Zach Braff, 2017) and The Old Man & the Gun (David Lowery, 2018); superhero feature Logan (James Mangold, 2017); and even the animated film Up (Pete Docter, 2010) were just some of the stories that effectively amplified the image and identity of aging screen stars.

The authentic celebration in these films of actors like Stallone, Streep, Willis, and Ford, alongside Diane Keaton, Jack Nicholson, Morgan Freeman, Robert De Niro, Clint Eastwood, and Robert Redford, who are adept at portraying the vulnerabilities, anxieties, and frightening realities of older age, sits of course within a Hollywood industry that—despite casting these older actors—relentlessly promotes a culture of youthfulness. But with Stallone and De Niro both de-aged in the sports drama Grudge Match (Peter Segal, 2013), and the latter again in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019), such techniques have become the aging star’s predictable next step as they engage a new kind of digitally enhanced screen performance. Scorsese’s gangster film in particular placed the spectacle of the de-aged male body front and center of both its marketing materials and its time-hopping narrative of crime and punishment. The extensive digital effects deployed by ILM to make actors De Niro, Al Pacino, and Joe Pesci appear decades younger account not only accounted for a large proportion of The Irishman’s $159 million budget, but provided the technology with a degree of mainstream acceptance given Scorsese’s willingness to openly embrace de-aging and alleviate more hardened conceptions of its visual and creative possibilities. These spectacular images reconjured by VFX artists from out of the past have not only come to epitomize the durable impact of aging boomers on contemporary production trends; they have also emerged at a time when there are ongoing national conversations gripping American news media around aging and seniority. The announcement made in July 2024 by US President Joe Biden that he was exiting the presidential race followed widespread concerns over his erratic behavior and supposedly diminished mental acuity, despite his 40-year political career. Even during the previous presidential campaign, Republican rival Donald J. Trump had popularized the “Sleepy Joe” moniker to persuade the electorate that Biden was unfit for office. Both Biden and Trump are well beyond retirement age in the US (the average age of the US Senate is over 65 too), and, at 78, Trump is only three years younger than the outgoing president, making him the oldest party candidate in US political history. The recent de-aging of octogenarian Ford for the opening 25 minutes of Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny (James Mangold, 2023) provides yet more evidence of the growing latitude that de-aging affords Hollywood storytellers, with their reliance on extended universes, narrative flashbacks, and split timelines. But with the not-so-sleepy Ford only four months older than Biden, his recent CGI-driven appearance as an athletic fortysomething is one of many performances that also mess with our sense of history by providing the comfortable and attractive fantasy of youth at a time when America’s political landscape is growing increasingly fraught in its equivalences between seniority, competency, and the aging lawmakers involved in its future.

Ant-Man and the Wasp (Peyton Reed, 2018).

4. GENDER AND DE-AGING

If de-aging represents the dominant tendency of recent commercial cinema, then digitally enabled processes of falsification equally reflect both Hollywood’s enduring fascination with the glamorous physiognomy of a star and the next stage in the development of technologies used to control, manage, and exhibit such star images. Acting has always been a craft, a practice, a skill, and a set of techniques “variously defined and valued, in its different intersections of technology, art and culture.”11 In digital de-aging, however, the meeting of technological processing and the screen performer is raised to a higher pitch of emphasis. As Claus’s comments regarding Captain America: Civil War make clear, digital de-aging may be thought of as falling somewhere between the dramatic facial alterations of plastic surgery and the softening effects of lighting developed for silent-era film stars, in which the “feminine white light” allowed a soft luminescent haze to radiate from the female performer in close-up and mark the star as a glamorous and uncontested centerpiece.12 Except, of course, digital de-aging departs in significant ways from cinema’s early refinements to photography by remaining an industry practice coded overwhelmingly as the preserve of masculinity. Female stars are rarely afforded the same digital processes of rejuvenation as their male counterparts, despite the industry’s aversion to the aged female body. Academic Josephine Dolan argues that faced with the choice of whether to use CGI airbrushing and “technologies” to manage the female star’s older appearance, “the Hollywood conglomerate … chooses instead to continue casting younger stars wherever possible, except for the few older stars, like Streep and [Judi] Dench, who are so acclaimed for their acting ability that they are untouchable.”13 While the female body at the first visible sign of aging remains largely pathologized, disavowed, and incompatible with Hollywood’s growing suite of de-aging procedures, de-aged representations have been made widely available to older (typically white) men, who are given the dual benefit of appearing both as their truthful older selves and as CGI-assisted younger versions all within a film’s runtime.

The industry double-standard that frames de-aging means that little has changed since the writer and critic Susan Sontag identified the different ways in which women and men are made to experience maturity. In a piece for the Saturday Review in September 1972, Sontag argued that “this society offers even fewer rewards for aging to women than it does to men,” and that “beauty, identified, as it is for women, with youthfulness, does not stand up well to age.”14 By comparison, masculinity is “identified with competence, autonomy, self-control—qualities which the disappearance of youth does not threaten.”15 Hollywood’s now-regular turns toward digital de-aging are therefore defined by many of the same uncomfortable truths that are involved in the cultural politics of aging, albeit assisted by new computational logic. Hollywood’s men are viewed as competent and in control well into old age, cast on the basis of such gendered assumptions before being given the further advantage of digital de-aging procedures that reanimate their languid bodies as younger digital sculptures. Women are not only made expendable within Hollywood’s well-established ageist system but are further detached from the technical wizardry that so regularly engages audiences in the novel attraction of youth.

Gemini Man (Ang Lee, 2019).

5. RACE, DISCRIMINATION, AND DE-AGING

The technological advancements in digital de-aging that have prompted a much-needed reckoning with Hollywood’s female aging problem can also help identify the discriminatory structures, misclassifications, and disparities encoded into the digital architecture of contemporary information technologies. Such technologies casualize biases and forms of prejudice through rapid algorithmic processing that manage our exposure to seemingly “neutral” information.16 Describing the digital de-aging of Will Smith for Gemini Man (Ang Lee, 2019) as “cinema’s first Black photorealistic digital human” and (still) one of the very few non-white stars awarded the de-aging treatment, Tanine Allison implicates the techniques used in creating computer-generated youth within highly racialized histories of technology-enabled discrimination, asking “how technology imbues the racist legacy of the past into the digital tools of the present and future.”17 Just as Hollywood lighting of the 1920s was refined through its ability to effectively illuminate white faces, and given that “the norm for correct lighting in Hollywood was what was known as ‘North’ lighting, light from the land of white people,” the noticeable swerving of Black stars within Hollywood’s digitized spectacle of youth speaks to the computational limits of algorithms that likewise manifest a troubling inability to render non-white bodies.18 A study by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) conducted throughout 2019 found clear racial disparities in the facial recognition tools developed by Microsoft, Amazon, and IBM; they were significantly less accurate when recognizing darker skin tones. In June 2020, Forbes reported that MIT Media Lab’s Joy Buolamwini and Timnit Gebru from Microsoft Research had found “gender classification systems based on facial recognition “performed best for lighter individuals and males overall,” and “worst for darker females.”19 The lack of de-aging afforded to actors of color ultimately reproduces the kinds of inequities that are algorithmically ingrained into automated surveillance technologies and contemporary facial analysis, serving to “reproduce historical inequities in a new form” and, like the insidious and incarcerating capabilities of global recognition software that assigns risk and suspicion to specific bodies, they shape the world in similarly unfair and irregular ways.20

Whiteness undoubtedly remains digital de-aging’s default setting. The technology therefore appears to align with other kinds of digital processes and platforms that have secured the uncontested hegemonic power of the white body, from the dominant white racial frame that has informed the design, appearance, and behavior of humanoids, robots, and cyborgs to the racial and ethnic coding of voice interactive technology consolidating the computer as “implicitly understood as white.”21 The lack of an intersectional project to Hollywood’s aggressive “youthing” tactics ultimately positions de-aging technologies and its accompanying ideologies at the sharp end of how we can, and do, think about and through the body, the human, and the self. The overlap between the virtual recreation of youth and longstanding registers of inequality only serves to reinforce de-aging with uneasy points of continuity with such histories of discrimination, and, for all its claims of effortless rejuvenation and politics of renewal, the same old historical prejudices and limited opportunities of the past continue to influence the instability of identity in the digital present. Studies of algorithmic agency within (and beyond) information processing already tell us how contemporary digital culture assigns primacy, visibility, and authority to material in ways that not only disrupt our engagement with and proximity to data but also shape the authority of particular identities through their enforced marginalization and occlusion. De-aging seems mired in the same selective capabilities of the computer—a literal technology of the young subversively circulating within the residual paradigms of an old medium and, perhaps appropriate given the persistent rumors of James Dean’s imminent digital resurrection from beyond the grave, the perfect crystallization of Hollywood’s latest irresistible force.

Here (Robert Zemeckis, 2024).

6. DE-AGING THEN, NOW, AND NEXT

As a potent form of digital stardom, the de-aged (or perhaps “anti-” or even “non-” aged) body has marked a turning point in the way we look at and listen to people onscreen, offering a new kind of virtual body that sits squarely between earlier forms of digitally enabled posthumous performances—like Oliver Reed in Gladiator (Ridley Scott, 2000) and “live” holography (featuring the digital reconjuring of stars like Tupac, Whitney Houston, and Roy Orbison). It also offers the newer spectacle of virtual concerts (notably the recent ABBA Voyage stage tour in London) and the current era of online digital deepfakes and AI-generated synthetic speech programs. Framed by these many interfaces and encounters between the human and the computer, the progressive transformation of digital imaging techniques into sophisticated tools of “youthmaking” throughout post-millennial Hollywood cinema has sold the promise of timelessness to stars now frozen in time via computer graphics—reconjured, reconstructed, and restored as a new kind of eternal data asset. Yet the narrative of technological immortality is, perhaps expectedly, one of loss as much as gain. Hollywood’s reliance on de-aging as both a screen attraction and storytelling device creates a potential barrier to the careers of those younger stars whose breakthrough opportunities might legitimately be curtailed by an industry now able to cast any aging star as their younger self. Cinema’s virtual recreation of youth therefore enforces for the boomer market a vital sense of history through a nostalgic mining of images and icons of the past, yet it risks being caught in a loop that replays and reiterates stars so that they can stay forever young. De-aging effects are central to Zemeckis’s Here (2024), which follows actors Tom Hanks and Robin Wright from teenagers through to middle and old age, and suggests the clear storytelling potential permitted by de-aging technology alongside the enduring box-office novelty of digital doppelgängers.22 But whether lucrative opening or dangerous trapdoor, the virtual recreation of youth as a new standard filmmaking practice in Hollywood has sharpened our understanding of aging through its opposite in ways that reflect a profound political cultural shift in what it means to grow older today.

- Aaron Couch, Mia Galuppo, and Borys Kit, “Meet the New A-List: The 10 Young Movie Stars Taking Hollywood by Storm,”The Hollywood Reporter (May 24, 2024). ↩

- Couch, Galuppo, and Kit, “Meet the New A-List.” ↩

- James Russell and Jim Whalley, Hollywood and the Baby Boom: A Social History (London: Bloomsbury, 2018), 203. ↩

- Sally Chivers, The Silvering Screen: Old Age and Disability in Cinema (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2011), xvi. ↩

- Barbara Robertson, “Face Off,” Computer Graphics World 29, no. 6 (June 2006). ↩

- Robertson, “Face Off.” ↩

- Carolyn Giardina, “Johnny Depp to Kurt Russell: How ‘De-Aging’ Stars Became Hollywood’s VFX Trick Du Jour,” Hollywood Reporter (May 30, 2017). ↩

- Trent Claus quoted in Carolyn Giardina, “How ‘Captain America: Civil War’ Turned Robert Downey Jr. Back Into a Teen,” The Hollywood Reporter (May 10, 2016). ↩

- Quoted in Hugh Hart, “‘Indiana Jones and the Dial of Destiny’ VFX Artists on De-Aging Indy,” Motion Picture Association (July 10, 2023). ↩

- Some of these companies include the Ukrainian tech startup Respeecher, and US-based Replica Studios, Descript, and Modulate. ↩

- Lisa Bode, Making Believe: Screen Performance and Special Effects in Popular Cinema (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2017), 184. ↩

- Patrick Keating, Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir (New York: Columbia University Press, 2010), 213. ↩

- Josephine Dolan, Contemporary Cinema and ‘Old Age’: Gender and the Silvering of Stardom (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 221. ↩

- Susan Sontag, “The Double Standard of Aging,” The Saturday Review (September 23, 1972): 31. ↩

- Sontag, “The Double Standard of Aging,” 31. ↩

- See Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression - How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018). ↩

- Tanine Allison, “Race and the digital face: Facial (mis)recognition in Gemini Man,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 27, no. 4 (2021): 1000, 1013. ↩

- Richard Dyer, The Matter of Images: Essays on Representations Second Edition (London & New York: Routledge, 1993), 152. ↩

- Larry Magid, “IBM, Microsoft And Amazon Not Letting Police Use Their Facial Recognition Technology,” Forbes (June 12, 2020). ↩

- Allison, “Race and the digital face,” 1009. ↩

- Liz Faber, The Computer’s Voice: From Star Trek to Siri (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2020), 11. ↩

- Zack Sharf, “Tom Hanks and Robin Wright Are De-Aged by Decades in ‘Here’ First Look Photos; Robert Zemeckis Reveals the Camera Never Moves in 104-Minute Film,” Variety (June 25, 2004). ↩

What's Your Reaction?

![[FREE EBOOKS] Hacking and Securityy, The Kubernetes Book & Four More Best Selling Titles](https://www.javacodegeeks.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/jcg-logo.jpg)

![AI in elementary and middle schools [NAESP]](https://dangerouslyirrelevant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NAESP-Logo-Square-1.jpg)