How One California Neighborhood Rebuilt After a Devastating Fire

Santa Rosa’s Coffey Park was destroyed in 2017—but mostly recovered. It could be a model for Altadena and Pacific Palisades.

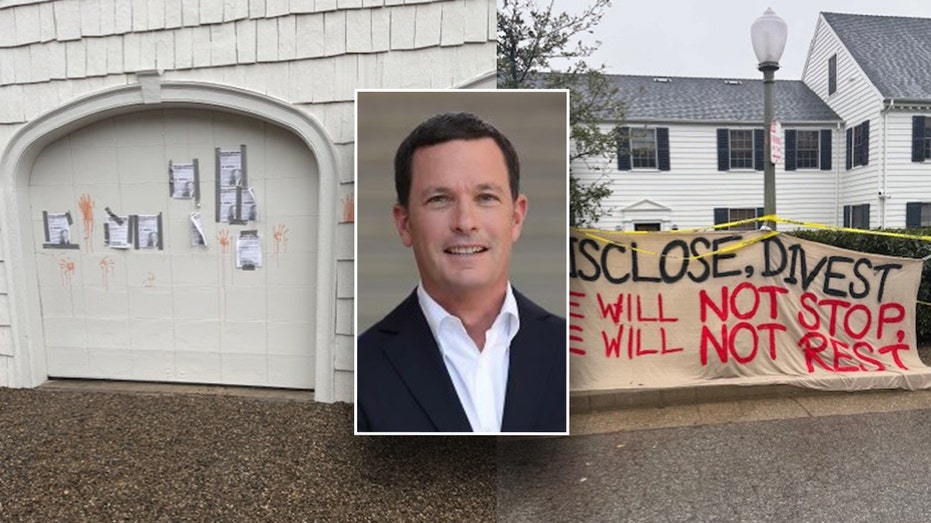

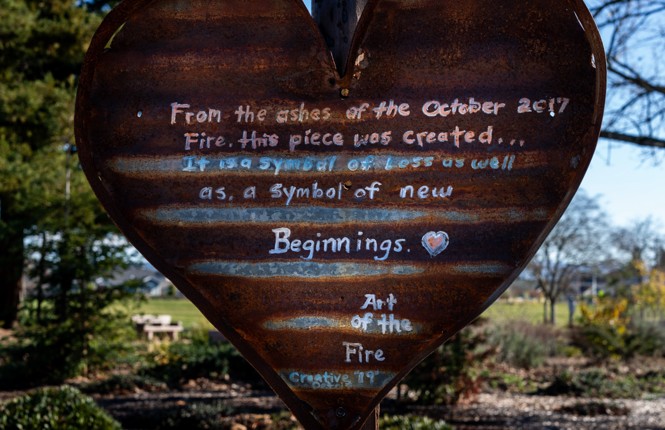

On the night of October 8, 2017, a small fire ignited near the northern tip of Napa Valley. Hot, dry winds gusting up to 80 miles an hour drove the blaze southwest toward the city of Santa Rosa, where it hopped over Highway 101––six lanes wide at that point––into neighborhoods, including one called Coffey Park. Nearly everything in that subdivision, including 1,422 houses, burned completely.

Yet today, a casual visitor would not think the neighborhood was the site of a recent catastrophe, instead finding custom homes with tidy yards, clean sidewalks, and trees that have matured into juveniles. That’s because Coffey Park residents rebuilt and reoccupied 80 percent of the houses there within three years. The recovery wasn’t total. Five Coffey Park residents died in the fire. Some people decided to relocate. A few lots remain empty. But the community has endured, and in many ways is thriving, or so several residents told me after I knocked on their doors last month, looking for lessons that could be useful for people displaced by the recent Los Angeles–area fires in Pacific Palisades and Altadena.

What do you know now, I asked dozens of residents, that you wish you had known when you lost your house? I also asked local officials for their reflections on how to rebuild.

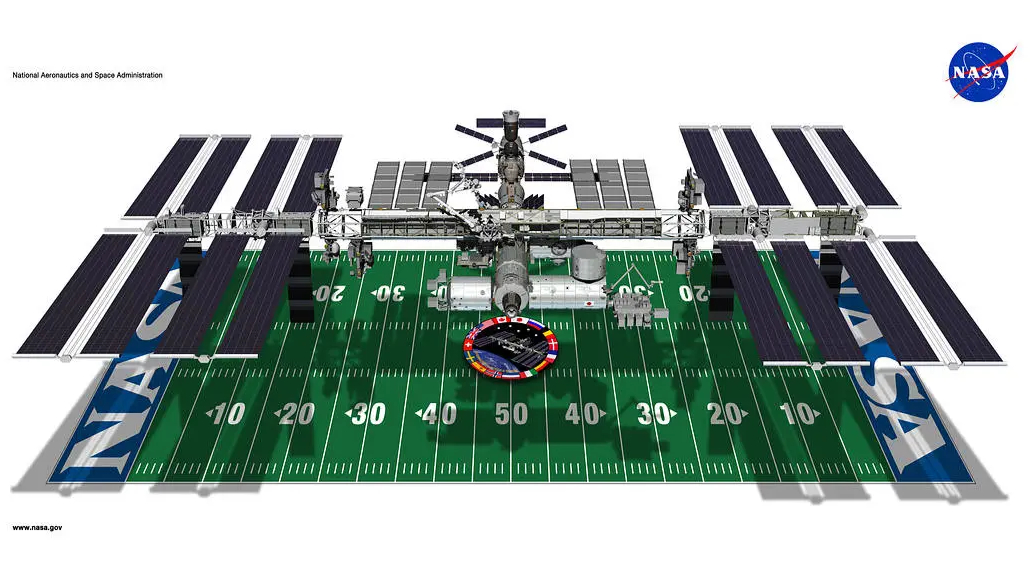

Santa Rosa, with roughly 175,800 residents, is far smaller than Los Angeles (population 3.8 million), let alone L.A. County (population 9.7 million), with many attendant differences in how the local government runs. And the number of structures destroyed in the Palisades and Altadena fires combined is nearly three times what Santa Rosa lost in 2017. But like Pacific Palisades and Altadena, Santa Rosa lost whole neighborhoods that no one expected to be consumed by wildfire, including Coffey Park.

[M. Nolan Gray: How well-intentioned policies fueled L.A.’s fires]

Santa Rosa officials emphasized to me that, in their experience, recovery requires local government to be flexible. But perhaps the most important transferable lesson that I gathered on my visit there, one touted by both residents and officials, is that neighbors can hasten their area’s recovery if they organize. Banding together helped Coffey Park residents in conflicts and negotiations with federal, state, and local officials. And it didn’t just yield more political power. It helped neighbors benefit from one another’s strengths, compensate for their own weaknesses, and create a stronger sense of community than before.

At 9:45 p.m. on the night the fire started, Von Radke was upstairs in the two-story house in Coffey Park where he and his wife had lived for more than 25 years. He’d undergone hip-replacement surgery two weeks prior and was turning in early. He recalls the wind blowing mightily as he drifted off to sleep. Hours later, he woke up and smelled smoke, but, groggy from painkillers, he at first dismissed it. Eventually he woke his wife, Jan, and hobbled downstairs. When he looked out a window, he saw embers in the air and 40-foot-tall Italian cypress trees bending 45 degrees in the wind.

It was past time to flee. But just backing out of the driveway took five minutes. The whole neighborhood was trying to evacuate. Traffic stopped for 20 minutes or more. Von saw people trying to fight fires with garden hoses, and more and more houses aflame. He and Jan might need to flee on foot, he thought, knowing how hopeless that would be in his condition. “For the first time in my life, I thought I was going to die,” he recalled. Finally traffic started to move.

Like many others who saw the fire up close, Radke went on to suffer “a significant amount of PTSD,” he told me. When we spoke in the front yard of his rebuilt home, a small two-story house surrounded by a well-tended garden, he focused on the psychological needs of the survivors. In the months after the fire, while they were still scattered in various hotel rooms and rentals, some of his neighbors began convening to talk through their escape experiences, their struggles, and how to rebuild. The best-known gathering came to be called Wine Wednesdays; it still occasionally takes place. To work through his own experience, Radke said he found a therapist who donated his services to fire survivors.

“It’s psychologically challenging to let people help you––to go to the local school and pick through donations of hand-me-down clothing to get you through those first weeks––but it’s important to learn a bit of humility,” Radke said, “because people want to help and you need help.”

Once the fire was out, Coffey Park residents were eager to return to their properties, and confused and frustrated by not knowing when they would be allowed in. Jeff Okrepkie, who’d lived in the neighborhood for five years, craved reliable information, and had more ways of getting it than most: As a commercial-insurance agent, he had colleagues who dealt with homeowner’s insurance and contacts with developers and contractors.

What we need, he thought, is a forum where residents can gather to ask questions and get accurate answers from knowledgeable sources. He called a friend at a nearby junior college who agreed to donate use of its auditorium, and spread the word about a community meeting. Officials from the city, builders, and insurance experts were all on hand. “I thought I had done my good deed,” he told me. “Then people started asking me, ‘When is the next meeting?’”

[Read: What the fires revealed about Los Angeles culture]

With Sonoma County Supervisor James Gore, Okrepkie organized a bigger town hall, drawing hundreds of attendees to an arts center. At that gathering, Coffey Park residents divided themselves into five groups based on their addresses, and each group nominated a captain to represent them. Weekly meetings followed, and soon Okrepkie founded Coffey Strong, a nonprofit to help residents get back into their homes as quickly and easily as possible. “Organizing in that way helped us continue to share information, but more importantly, it legitimized us in the eyes of government agencies,” he said. “If they were contacted by Coffey Strong, it wasn’t one person calling; it was one person who represented thousands.”

The group began to solve problems no one had anticipated. When the neighborhood had been built, the developer had constructed walls around its edges that residents assumed belonged to the city but were in fact the responsibility of homeowners. Had residents known that earlier, they would have had the damaged walls hauled away during the free debris removal offered to them as part of disaster-relief efforts. Now they faced having to pay thousands of dollars for the walls’ removal, and still more to replace them piecemeal. Coffey Strong raised $500,000 for the project and persuaded contractors to donate labor.

After many of the initial hurdles to rebuilding had been cleared, the U.S. Postal Service told residents that instead of having mailboxes at their houses, as before, they’d now have centralized mailboxes, a proposal that many of them strongly rejected. “When your neighborhood burns down, it’s a total loss of control, and for a lot of people, rebuilding your home, which involves making a lot of choices, restores a sense of control,” Okrepkie said. “So when someone from the federal government comes and tells you, We’re doing this in a way that’s worse than what you had, and you have no control, it upsets people a lot.” Under pressure from Coffey Strong, as well as allies in the city, the Postal Service reversed course.

While Coffey Park residents were organizing, city staffers in Santa Rosa had to figure out how to support people affected by the fire citywide. Initially, the new demands were almost overwhelming: First responders were exhausted; municipal structures and infrastructure had been destroyed in the fire; city officials had to coordinate with Sonoma County, the state of California, FEMA, and more. Thousands of residents were displaced, all wanted information, and meanwhile, normal city business wore on.

Gabe Osburn was a municipal employee working in a role unrelated to fire recovery who lived in a house just beyond where the fire had reached. Feeling survivor’s remorse, he expressed interest to his boss in helping with the recovery. Osburn started attending community meetings for fire victims as a representative of the city and soon was assigned to advance fire recovery full-time on behalf of the planning department; he would be among the primary city employees working with residents to rebuild, and ultimately attended more than 300 meetings with fire victims, he told me. The goal, Osburn said, was not just to restore the 5 percent of the city’s housing stock that had been lost. “It was important for us to keep the fire victims here,” he said. “They were the fabric of our community.”

Early on, Osburn feared that the area’s small construction industry would be unable to supply enough contractors, laborers, and materials to rebuild affordably. As it turned out, free markets and assistance from flexible regulators was a powerful combination. Builders responded to the new demand for construction. And the city offered steep discounts on building permits, created a permitting center dedicated to fire recovery, and worked with surveyors to go through the areas most affected by the fire instead of requiring each resident to pay their own surveyor to clarify property lines. If residents wanted to change the footprint of their house, city planners worked with them. There were limits to what the city would allow, but multiple residents told me that the staff tried to get to yes, rather than insisting on strict adherence to the rules as they’d existed before the fire.

Walking around Coffey Park, I met some of the beneficiaries of that government flexibility. Julio Alvarez told me that he and his wife had been underinsured. A discount on permits enabled them to rebuild. And the ability to change their floor plan from two stories to one has helped the couple as they get older.

Rod Julianus was at first determined to rebuild his house exactly as it was. Then he thought better of it: The house had been filled with furniture that his late grandfather had made in a factory in Holland and given to his parents upon their marriage. He realized that if he rebuilt the same house with the same floor plan, he would spend the rest of his life looking at the spots where that furniture had been. Switching floor plans made his psychological recovery easier. He advises anyone planning to rebuild to consider if changes might help them, too.

Will Los Angeles be as good a municipal partner to its fire-affected residents as Santa Rosa was? L.A. officials have already started waiving some building requirements, and the city certainly has more resources than Santa Rosa. But I’ve heard horror stories from both homeowners and businesses about the city’s endlessly complex rules, so I fear that, because its bureaucracy is so big and difficult to navigate, it could fail the fire victims. (Pacific Palisades is part of the city of Los Angeles, while Altadena is an unincorporated community in L.A. County and will be subject to county building rules and agencies.)

[Nancy Walecki: The place where I grew up is gone]

Can residents of Altadena and Pacific Palisades improve their recovery by organizing themselves? There, I am more hopeful. Like any neighborhood, even a suburban one where the homes are mostly of similar size and value, Coffey Park is filled with people of all sorts. Knocking on its doors, I encountered friendly invitations to come inside and gruff suspicions that I was soliciting. I met professionals with contacts in industries as varied as home construction and therapy, canny people you’d want negotiating a lawsuit on your behalf, and warmhearted sorts you’d want commiserating with you after the loss of a wedding ring or a pet. As individuals, everyone in the neighborhood lacked something important that recovery required. Collectively, they had the qualities and connections they needed.

Santa Rosans have gotten used to sharing their knowledge with other communities that suffer from fires. Some of the advice they relayed to me was practical and time-sensitive. Remember to cancel your cable bill or home alarm system or land line so you don’t continue to be charged. Walk your lot with a metal detector before the rubble is hauled off. And start looking for and vetting contractors now––everyone who rebuilds will need one. When you find one, have a lawyer look at the contract. Before submitting a list of lost objects to your insurer, walk through a home-goods store to jog your memory of forgotten items. Residents also recommended resources including After the Fire, an organization that helps communities recover from wildfires, and United Policyholders, a nonprofit that helps insurance consumers.

Jeff Okrepkie now sits on the city council, and Gabe Osburn is the head of planning; both have shared what they’ve learned with officials and residents of Los Angeles, Maui (the site of the 2023 Lahaina fire), and beyond. As for Coffey Strong, the nonprofit is now inactive, having succeeded in its core mission: getting residents home. The group’s website remains online as a resource. Among its attestations: “Nobody can or should shoulder all of this alone.”