From polar bears to polar vortex: How Columbia Sportswear uses nature to protect us from it

I spent four days in Iceland learning about biomimicry and how it led to arctic animal-inspired outerwear. The post From polar bears to polar vortex: How Columbia Sportswear uses nature to protect us from it appeared first on Popular Science.

I’m standing on a corner in Reykjavík, the most flagrantly fragrantly delicious cinnamon roll I have ever had in my hand, and I am pouring sweat. It’s not because I worked hard to get this blissful brauð; it’s a leisurely 10-minute walk from my hotel. It’s not because it’s unseasonably warm; it’s Iceland in late September and a brisk 40 degrees Fahrenheit. It’s because I’m wearing Columbia Sportswear Omni-Heat Infinity baselayers, and I have underestimated their insulating capacities—a mistake I will not make twice. It’s a mistake I shouldn’t have made at all.

I spent several days prior testing out breathable membranes and thermal-reflective tech. Columbia’s gold metallic foil—introduced in 2021—helped insulate Intuitive Machines’ lunar lander when it was sent to the actual Moon in February 2024 (and when it launched again in 2025). In space, nobody can hear you sweat, but I’m walking through landscapes that only resemble Mars. And I’m audibly panting.

I’ve trudged across the Solheimajokull glacier and been told that Omni-Heat Infinity would be a bit extra for those circumstances, so why I thought I needed it for a casual city stroll, well, I’m feeling the heat from that … I’m taking the heat for that. I packed Omni-Heat Infinity in case temperatures plunged below freezing. I should have stuck with what I’m actually in Iceland to learn about: Omni-Heat Arctic, Columbia Sportswear’s latest insulation system developed through research on polar bear pelts and demonstrated on less carb-focused, more high-output adventures. And what better place to test fabrics than where weather is constantly in flux.

Iceland is a land of layers—both wandered and worn. On the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, where the Eurasian and North American plates slowly separate, the country is resigned to be redesigned as the Earth shifts and strains. But because a place is cold doesn’t mean it is unkind. A close-knit society on an unraveling rock, the Iceland I experience is a warm, self-reliant culture that demands warm, resilient clothes.

I’ve only been in the country a few hours before I see a new road being freshly graded on top of what looks like last week’s lava. I’ve only been in the country a few more hours before it rains, shines, pours, and then the clouds part. Over the course of one day I’ll be doused winding behind the wind-whipped waterfalls, snake between surging sneaker waves, then scramble up the ashy veins of ice ridges. For every hour that’s brooding and bleak along the black sand coastline, there will be one that’s calm and bright beside thermal rivers. Hiking through the Reykjadalur Valley, we meet Skylar, who is backpacking solo through Europe and proudly shows off his one constant companion: a Columbia Sportswear flannel.

Tranquility. Volatility. “If you don’t like the weather, wait five minutes” is a fitting expression and apt alert that you should always approach travel in Iceland with all manner of apparel handy. It’s a saying you’re just as likely to hear in Beaverton, Oregon, home to the Columbia Sportswear Company.

Field-testing in Iceland is a first for our host, Director of Communications Andy Nordhoff, but this type of terrain isn’t foreign. Oregon may not be constantly altered by tectonic tension the way Iceland is, but it’s no stranger to maritime influences and geothermal forces. It’s a dramatic backdrop shaped by the slow grind of time and upheaval—weathered smooth in places, rough in others. It’s a landscape that has shaped Columbia since the company was formed in 1938. What started as a hat company is now one tough mother of an outfitter producing apparel and accessories for challenging environments.

And if there’s one thing folks from Oregon and Iceland know, it’s that there’s nothing worse than standing in a coat that has you remembering rather than feeling what it’s like to be warm or dry. To be present in adventures, you can’t be worrying about your clothes. A majority of activities in Iceland—from exploratory tourism to olfactory art collectives—are anchored in cultural reverence for natural resources and capturing the rejuvenating aura of the outdoors. And in a way, that’s the concept behind Omni-Heat Arctic, a solar-capture system. But before I found myself wrapped up in a fleece appreciating untamed beauty, Columbia’s in-house scientists spent years wrapped up in how nature solved the problem of thriving at extremes.

Speaking from the Columbia campus, Dr. Haskell Beckham, vice president of innovation, explains how the company set out to “have the warmest jacket without the weight of a giant, damp puffer.”

A puffer is, in the most basic terms, a bunch of chopped-up material stuffed in fabric. There’s down, there’s synthetic insulation, but it’s no matter what it’s operating with trapped air, which is low thermal conductivity. Still, humans constantly radiate heat, so the silver metallic Omni-Heat lining was introduced in 2010 to block that loss and reflect it back. Fast forward to 2021, and Omni-Heat Infinity introduced more surface coverage without impacting breathability, now with gold dots to tell the difference. Either way, they stood up to accelerated abrasion testing and real-world comfort testimonials. Plus the off-world partnerships with Intuitive Machines, who spoke the same language of thermal emissivity and solar reflectivity.

So, having successfully applied materials science to space, the Columbia lab started thinking about icons of the most extreme environments on Earth. And Arctic inhabitants quickly came up. Digging into scientific literature about polar bears, however, revealed gaps in the understanding of how they survive. So Beckham knew he had to get his hands on a polar bear pelt.

After trying the Oregon Zoo, Beckham followed a suggestion to contact the Burke Museum of Natural History at the University of Washington in Seattle. It turned out they did have a pelt that he could check out, like a library book, and he brought it back to the Portland area where it was studied for a year—placed in environmental chambers to measure how it reacted under a solar simulator at various watts per meter squared to mimic what it might see in a cold, yet sunny environment. And that’s when the Columbia team was able to shine some light on how polar pelts absorb light.

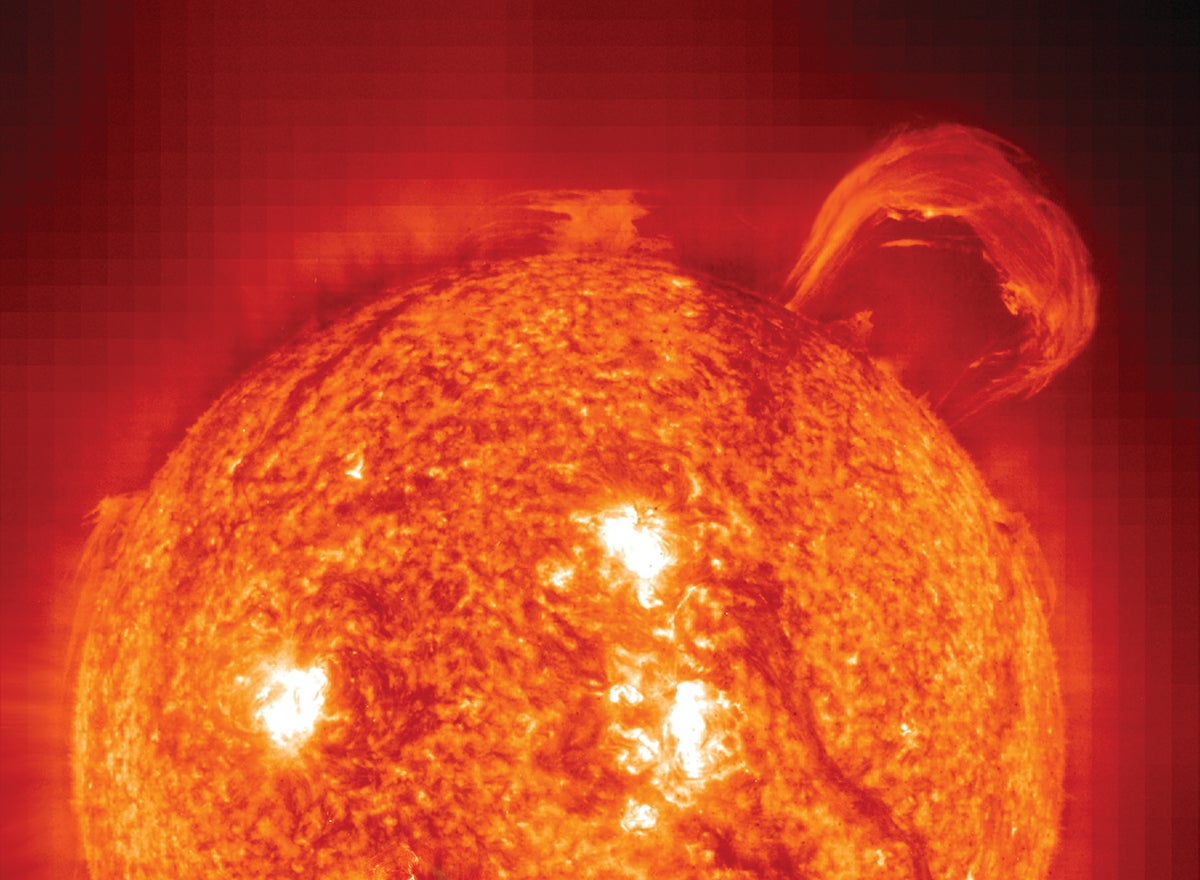

“We discovered that the fur itself is actually translucent, but not transparent,” explains Beckham. “This lets a degree of solar energy transmission through the fur. And the bear’s skin is pigmented, which helps convert solar energy into heat—just like a black T-shirt in a warm environment feels warmer than a white T-shirt, which reflects solar radiation. With this system the pelt harvested solar energy and converts it to heat, so we set about creating materials and material stacks that have the same effect, which is partially about color and partially about density.”

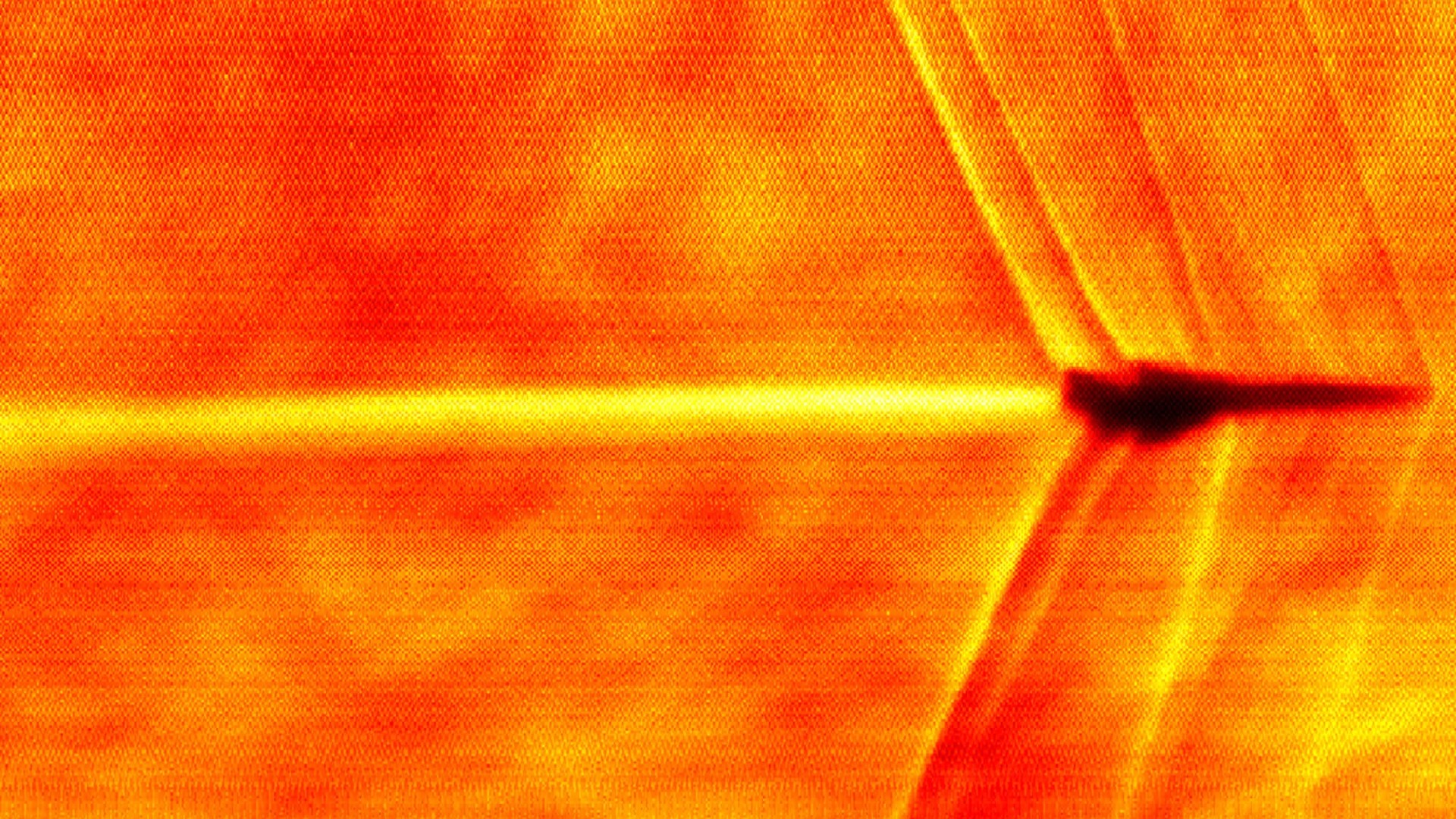

The end result, Omni-Heat Arctic, applies this discovery with thinner outer layers that allow sunlight to penetrate to the insulation (the equivalent of the underfur) and be converted closer to the body. However, unbroken black fabrics wouldn’t work, as the heat collects at the surface and is lost to the environment. It was imperative the solar radiation bypass the shell, go through the insulation, and be absorbed in a lining.

For the Arctic Crest Down Jacket, the Columbia lab finally settled on a lining patterned with triangles and dots. Multi-layered engineering allowed the material to have a layer of metal topped with a coating featuring a black pigment. That black coating absorbs the solar radiation and converts it to heat, which is then conducted toward the body, while also protecting that heat from dissipating into the cold.

And the team knew they nailed it when beta testers made unprompted comments about how it felt like the warmth amplified after the sun comes out, despite the external temperature.

“It’s a solar-boosted heat … like a biological greenhouse effect,” says Beckham. “That’s why the pattern on the puffer resembles a geodesic dome. On top of that, it’s a warmer jacket even when there’s no sunshine, thanks to how we engineer materials.

“The fleece works a bit differently since they don’t have that special low E [low emissivity] coating, but [the high pile and black yarn lining] do work in that way a pelt naturally works.”

As straightforward as all that sounds, Beckham’s research produced insight that challenged conventional wisdom, showing it’s not as simple as sunlight transferred through fur onto skin equals warmth. The fur density varies across the pelt, and as little as 3.5 percent of the light sometimes reaches the skin. So, an open question still remains about why the polar bear’s skin is black and what part it versus the fur truly plays in thermal regulation.

This, in a way, makes Omni-Heart Arctic an evolution, even an improvement on the natural means of solar transference. Confirmed by heat flux sensors, control of insulation, shell fabric/coating, lining, and moisture-resistant overlays allowed for garments with up to three times heat retention plus performance-oriented attributes. Core areas needing thicker covering and other areas needing flexibility and breathability can be targeted, while selectively absorbing sunlight promotes warmth without harmful exposure to UV.

Before this trip, my perspective on polar bears boiled down to “If it’s brown, lay down; if it’s black, fight back; if it’s white, say goodnight.” Now, I can appreciate what these creatures and Columbia Sportswear have done to address my mammalian shortcomings. Of course, when you think of a polar bear soaking up the Arctic sun, there’s a good chance you imagine it’s floating on an iceberg. While we didn’t go that far to test our textiles, we did take a sizable amount of moisture into consideration.

The Seljalandsfoss and Skogafoss waterfalls feel like veils between worlds—permeable but formidable. Piercing the multiverse requires preparation, however, and Columbia made sure we were ready with the OutDry Extreme Wyldwood shell jacket and pants. Thrown over the zip-up fleece, OutDry Extreme provided an impervious barrier without forming a moist bubble. With the hydrophobic film-like membrane laminated on the exterior (as opposed to the interior, topped by DWR-coated fabric), I didn’t worry about wet out or wet within. This orientation enhances breathability, allowing the interior fabric to wick perspiration away and more evenly distribute moisture vapor movement so no area gets overloaded. And as someone who constantly runs hot, I can vouch for its effectiveness. The Konos TRS OutDry Mid shoe kept my feet equally dry, stable, and cushioned throughout trail and town (and they remain my rainy day sneaker boots).

Having a successful solution doesn’t mean Beckham and his team aren’t looking at new bio-inspired emulations that can improve outdoor apparel, however. The water-repellent properties of the lotus leaf are of interest, as the plant’s microstructure enables water droplets to bead up and roll off effortlessly. This could lead to durable, chemical-free, water-resistant gear. And the structural color of butterfly wings, where microscopic structures rather than pigments create hues, could lead to vivid, long-lasting color without dyes—another sustainable solution. From the 3D printers and swatch prototypes in their fab lab to the computational modeling that allows them to go through infinite combinations of inspirations and materials, the Columbia Sportswear scientists pursue innovation and efficiency.

I’ve now lived in the Arctic Crest Down Jacket and Arctic Crest Sherpa Fleece from one shoulder season to the next, trudging through the most brutally cold winter in a decade. Soon, it will be time to hang them up in favor of windbreakers and lightweight rain shells. In the not-so-distant future, Columbia Sportswear will have cooling technologies to reveal. But the polar vortex surged southward again as I started outlining this piece. Despite the spring-like weather that followed, early-morning hiking and biking isn’t exactly balmy yet. And there are always new latitudes to explore with the right daypack. So, as long as there’s even a hint of crispness or clouds in the years to come, I’m happy to bundle up in biomimicry to help me grin and, well, bear it, warm as a fresh cinnamon roll.

The post From polar bears to polar vortex: How Columbia Sportswear uses nature to protect us from it appeared first on Popular Science.