Bog Bodies Lay Hidden in a Florida Pond for More Than 7,000 Years

It had been a bountiful autumn for the people who lived near Florida’s Atlantic coast more than 7,000 years ago. They had harvested prickly pears, sedge, hickory, and chestnuts in the subtropical forests that covered the land around their village. They had fished the sea, streams, and lakes with nets and bone hooks, catching catfish and sharks, and collecting shellfish. In the forests, they had hunted opossum, rabbits, and deer, fat after summer grazing. But even in this time of plenty, death was never far away. Accidents, disease, and violence could strike at any time. And now, as the harvest season waned, a young woman had passed away. Her people transported her body to the shores of a still lake near their village. There, on the muddy banks, they placed the woman on her side in a fetal position and wrapped her in cloth woven from palm fibers. Then they carried her into the water. They gently pushed her body under the surface, placing her so that she looked towards the setting sun. They drove freshly cut pine stakes through the palm-fiber textile and into the dense peat that made up the bottom of the lake. And then they waded ashore, leaving her among dozens of similar underwater graves marked by pine stakes. While we often associate bog bodies with the northern European cultures of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the practice existed in what's now the United States much earlier, and this young woman is just one of many individuals unearthed from the peat of now-vanished lakes. Her skull would serve as the basis for a forensic reconstruction known as the Windover Woman, which allowed museum visitors to look into the eyes of this ancient inhabitant of the Florida wetlands. The lake burial location, known today as the Windover Archaeological Site, is just a few miles across the Indian River from the John F. Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral. It was discovered in the early 1980s during excavations for a housing development. A human skull found at the site initially prompted police involvement, but radiocarbon dating revealed the remains were from the Early Archaic Period, around 6000 B.C. Subsequent archaeological excavations eventually turned up 168 skeletons. Humans arrived in Florida as early as 14,000 B.C., during the tail end of the last ice age when the landscape would have been arid and colder than it is today. About 10,000 years ago, climatic changes raised sea levels and turned the region into a lush and verdant landscape dotted with lakes and ponds such as the one at Windover. The inhabitants of this area lived, hunted, and gathered both in forests and along the coast. They most likely lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving between areas seasonally to maximize resource gathering. Windover’s archaeobotanical finds—such as ancient pollen and seeds—suggest the site was primarily occupied in the late summer and autumn rather than the spring or early summer. The lack of scavenger marks on the bones of the bodies found at Windover means that the people were likely buried there soon after dying. And the dead of Windover were not sent off to the afterlife empty-handed: Their families also placed grave offerings in the shallow water near the bodies. Items recovered include points made from antler and bone, carved pelican bones, stone tools, and even a bottle-gourd used to transport liquids. It is not known what kind of afterlife belief system these Early Archaic occupants of the area had, or why they buried their dead underwater. Their tradition, however, would provide archaeologists with precious details about their lives. Thick peat, which encased the human remains and artifacts, created an oxygen-starved environment. This led to the exceptional preservation of organic materials such as bone, wood, antler, and fiber textiles, which are usually among the first things to degrade at most archaeological sites. The peat preserved more than artifacts and bones: Archaeologists noted a mushy substance present inside the cranium of one of the skulls during excavations. It soon became clear that the substance was brain matter, and subsequent digging turned up several intact but degraded human brains, still inside their ancient skulls. Scientists analyzed genetic material from both the brain tissue and bones of some of the individuals found at Windover several years ago. The results, published in the early days of ancient human DNA analysis, suggested shared ancestry with ancient people in Asia, but also that the Windover population was not closely related to other Native American groups. While DNA can reveal clues to their lineage, the remains of the dead can also tell us something about the values of the society in which they lived. Among the bones found at Windover are those of a 15-year old boy. In life, he suffered from spina bifida and also lost a foot, an injury that was tended and healed. Due to his disability, he could never have walked, yet his family and community cared for him. And when de

It had been a bountiful autumn for the people who lived near Florida’s Atlantic coast more than 7,000 years ago. They had harvested prickly pears, sedge, hickory, and chestnuts in the subtropical forests that covered the land around their village. They had fished the sea, streams, and lakes with nets and bone hooks, catching catfish and sharks, and collecting shellfish. In the forests, they had hunted opossum, rabbits, and deer, fat after summer grazing.

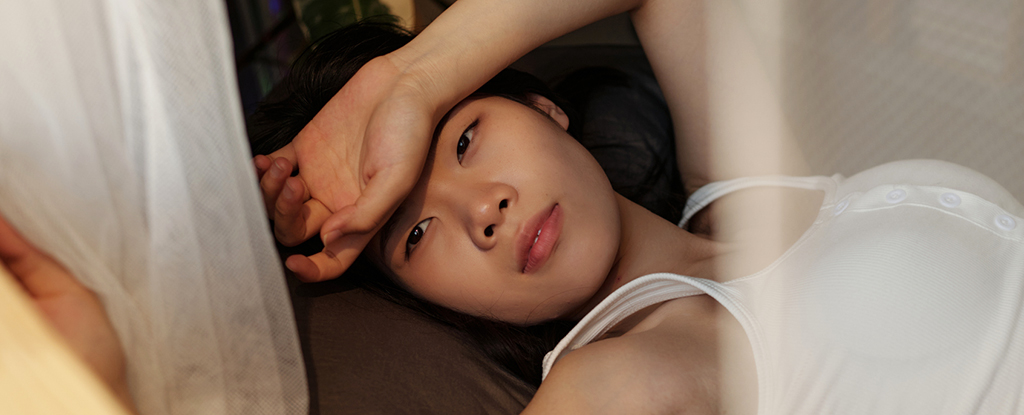

But even in this time of plenty, death was never far away. Accidents, disease, and violence could strike at any time. And now, as the harvest season waned, a young woman had passed away. Her people transported her body to the shores of a still lake near their village. There, on the muddy banks, they placed the woman on her side in a fetal position and wrapped her in cloth woven from palm fibers. Then they carried her into the water. They gently pushed her body under the surface, placing her so that she looked towards the setting sun. They drove freshly cut pine stakes through the palm-fiber textile and into the dense peat that made up the bottom of the lake. And then they waded ashore, leaving her among dozens of similar underwater graves marked by pine stakes.

While we often associate bog bodies with the northern European cultures of the Bronze and Iron Ages, the practice existed in what's now the United States much earlier, and this young woman is just one of many individuals unearthed from the peat of now-vanished lakes. Her skull would serve as the basis for a forensic reconstruction known as the Windover Woman, which allowed museum visitors to look into the eyes of this ancient inhabitant of the Florida wetlands.

The lake burial location, known today as the Windover Archaeological Site, is just a few miles across the Indian River from the John F. Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral. It was discovered in the early 1980s during excavations for a housing development. A human skull found at the site initially prompted police involvement, but radiocarbon dating revealed the remains were from the Early Archaic Period, around 6000 B.C. Subsequent archaeological excavations eventually turned up 168 skeletons.

Humans arrived in Florida as early as 14,000 B.C., during the tail end of the last ice age when the landscape would have been arid and colder than it is today. About 10,000 years ago, climatic changes raised sea levels and turned the region into a lush and verdant landscape dotted with lakes and ponds such as the one at Windover.

The inhabitants of this area lived, hunted, and gathered both in forests and along the coast. They most likely lived a semi-nomadic lifestyle, moving between areas seasonally to maximize resource gathering. Windover’s archaeobotanical finds—such as ancient pollen and seeds—suggest the site was primarily occupied in the late summer and autumn rather than the spring or early summer. The lack of scavenger marks on the bones of the bodies found at Windover means that the people were likely buried there soon after dying.

And the dead of Windover were not sent off to the afterlife empty-handed: Their families also placed grave offerings in the shallow water near the bodies. Items recovered include points made from antler and bone, carved pelican bones, stone tools, and even a bottle-gourd used to transport liquids.

It is not known what kind of afterlife belief system these Early Archaic occupants of the area had, or why they buried their dead underwater. Their tradition, however, would provide archaeologists with precious details about their lives. Thick peat, which encased the human remains and artifacts, created an oxygen-starved environment. This led to the exceptional preservation of organic materials such as bone, wood, antler, and fiber textiles, which are usually among the first things to degrade at most archaeological sites.

The peat preserved more than artifacts and bones: Archaeologists noted a mushy substance present inside the cranium of one of the skulls during excavations. It soon became clear that the substance was brain matter, and subsequent digging turned up several intact but degraded human brains, still inside their ancient skulls. Scientists analyzed genetic material from both the brain tissue and bones of some of the individuals found at Windover several years ago. The results, published in the early days of ancient human DNA analysis, suggested shared ancestry with ancient people in Asia, but also that the Windover population was not closely related to other Native American groups.

While DNA can reveal clues to their lineage, the remains of the dead can also tell us something about the values of the society in which they lived. Among the bones found at Windover are those of a 15-year old boy. In life, he suffered from spina bifida and also lost a foot, an injury that was tended and healed. Due to his disability, he could never have walked, yet his family and community cared for him. And when death claimed him, far too young, they carried him one final time to their ancestral burial ground.

The final burials at Windover date to around 5000 B.C. They show that the lake was in use for more than a thousand years, spanning dozens of generations. It’s unclear why the tradition came to an end locally. It’s possible that the community relocated or simply died out. But the practice of water burials continued regionally. Archaeologists have studied similar traditions at several other sites in South and Central Florida, including one discovered in 2016, near Manasota Key, that’s currently more than 20 feet underwater due to sea level rise. When the site was in use more than 7,000 years ago, it would have been a freshwater pond—just like Windover.

Even 4,000 years after the last individual was laid to rest at Windover, other people were placing their dead on platforms in a lake at a site now known as Fort Center, more than 100 miles to the south. Meanwhile, protected by the thick peat, the people of Windover waited to share their stories.

What's Your Reaction?