Be Like Sisyphus

How to embrace hopeful pessimism in a moment of despair

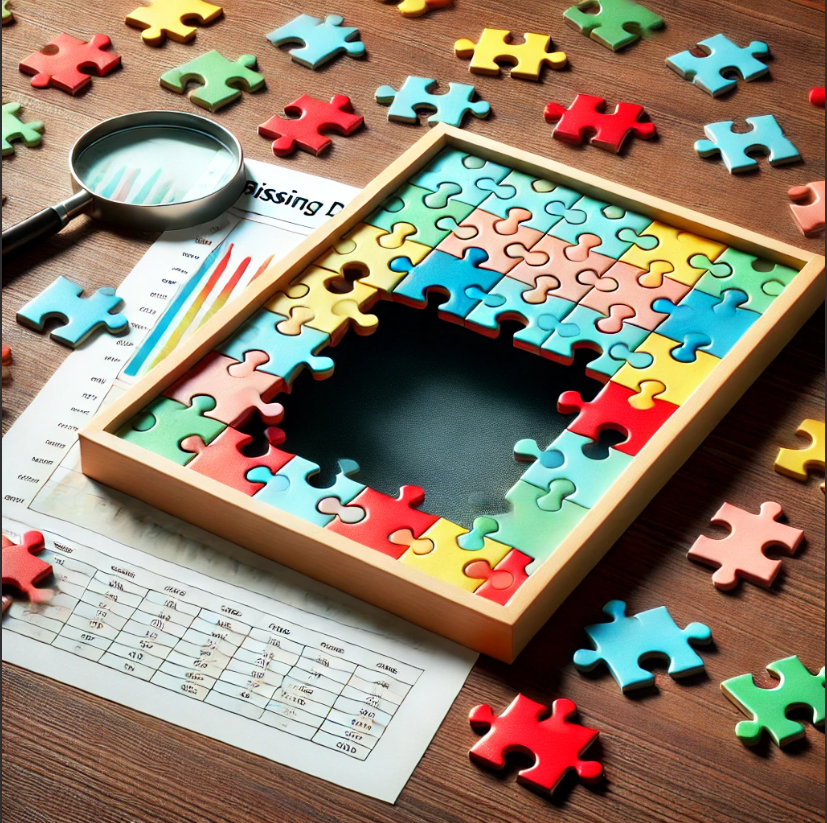

This anxious century has not given people much to feel optimistic about—yet most of us resist pessimism. Things must improve. They will get better. They have to. But when it comes to the big goals—global stability, a fair economy, a solution for the climate crisis—it can feel as if you’ve been pushing a boulder up a hill only to see it come rolling back down, over and over: all that distance lost, all that huffing and puffing wasted. The return trek to the bottom of the hill is long, and the boulder just sits there, daring you to start all over—if you’re not too tired.

In the Greek story of Sisyphus, the king was condemned for eternity to move a massive rock up a hill but never reach the summit. Albert Camus famously saw it as a parable of the human condition: Life is meaningless, and consciousness of this meaninglessness is torture. This is how I’d remembered Camus’ essay The Myth of Sisyphus, which describes an afterlife as devastating as that of Prometheus having his liver pecked out by an eagle anew every day. But when I reread it recently, I was reminded that for Camus, the king isn’t entirely tragic; he has some power over his existential predicament. Once he grasps his fate—“the wild and limited universe of man”—Sisyphus discovers a certain freedom; he gets to determine whether to face the futility of it all with joy or sorrow. “Each atom of that stone, each mineral flake of that night-filled mountain, in itself forms a world,” Camus writes. “The struggle itself toward the heights is enough to fill a man’s heart. One must imagine Sisyphus happy.”

This is a bleak model for those in lamentation over our current moment. But Camus’ brand of pessimism is apt, simultaneously acknowledging that sense of being cosmically screwed while knowing that finding purpose, and even some kind of hopefulness, is possible in a world that promises nothing.

Hopeful Pessimism, the title of the philosopher Mara van der Lugt’s new book, perfectly captures this oxymoronic attitude. It is an attempt to redeem pessimism’s Debbie Downer reputation. For starters, van der Lugt writes, pessimism is not the same as fatalism. Just because you believe that the sky is likely to fall does not mean that you think it necessarily will. Pessimism is simply “a refusal to believe that progress is a given.”

Van der Lugt’s main concern is arguably both more farsighted and more immediately pressing than any particular fire or election. As the world comes off the hottest year on record, weeks into a new one already marked by cataclysmic fires, she hopes to articulate a philosophical outlook for climate-change activists—a cohort with seemingly every reason to despair. On this topic especially, she sees the danger, and even “cruelty,” in optimism. She imagines how a pessimist and an optimist might approach the problem. As she puts it, the optimist would say, “There is every reason to believe we can turn the tide and prevent the worst impact from climate change. Our efforts to prevent climate catastrophe are likely to succeed.” The pessimist would say, “There is every reason to believe we cannot turn the tide and prevent the worst impact from climate change. Our efforts to prevent climate catastrophe are likely to fail.”

[Read: How to find joy in your Sisyphean existence]

Which attitude will lead to action? Van der Lugt thinks the pessimist’s is more motivating and sees a danger in the optimist’s, because if things look so generally bright, why should anyone get off the couch? The climate activist driven by pessimism has a sense of direness, of panic. They can’t assume the arrival of an imagined savior, such as some utopian technology or a conversion among all of the world’s leaders. Disaster, and grief about that disaster, is with them always, and so they feel that they have no choice but to act. Moreover, the presumption that individuals have supreme control over the direction of the world—when they very much do not—sets one up for perpetual disillusionment and pain. As Voltaire called it almost 300 years ago, optimism is “a cruel philosophy hiding under a reassuring name.”

So what about the hopeful part of hopeful pessimism?

I called van der Lugt, who teaches philosophy at the University of St Andrews, last week to ask her. Pessimism, after all, is not that hard to come by; just open the newspaper on any given day. Hope is another thing. But she insisted that a certain kind of hope is compatible with pessimism—so long as it obeys two ground rules. First, it should be built not on an expectation of what will happen in the future but instead on uncertainty, based on the fact—and it is a fact—that we just don’t know how things will turn out. “Things might get pretty bad, but there’s no telling if things could at some point get better again,” ven der Lugt told me. “Similarly, things might be pretty good; they could also get pretty bad again. So it’s never ever a closed story. The open-endedness of the future means that there’s always ground to stick with things that are worth fighting for and worth being committed to.”

This leads to her second condition: If hope can’t emerge from any concrete belief that you will actually achieve your hoped-for outcomes, then what can sustain it? Values, van der Lugt said. The simplest way to put this is to ask whether the cause or the change you are fighting for would still feel worth fighting for if you knew you’d never see it realized. Your hope is “value-oriented,” she said, when it is driven by principles such as justice, duty, solidarity with your fellow human, and just your sense of goodness. You act because you feel you must.

This formulation of hope immediately made me think of Václav Havel, the Czech dissident who would become the president of his country (and a thinker who has come to mind for me a lot lately). Havel was interviewed in 1985 precisely on this question of hope. He insisted that it was not a “prognostication” but rather “an orientation of the spirit”: Hope is “not the same as joy that things are going well, or willingness to invest in enterprises that are obviously headed for early success, but rather an ability to work for something because it is good, not just because it stands a chance to succeed.”

[Read: A mindset for the Trump era]

This is also the kind of hope—what van der Lugt refers to as “radical hope”— birthed in the most desperate of situations, a moment when all is truly lost, when even death seems certain, and people still find a reason to fight back. I think of the men whom Chris Heath wrote about in his recent book, No Road Leading Back. These were Jews and Russian prisoners of war who were forced by Nazi SS officers to do something unimaginably grotesque and inhumane: exhume the more than 70,000 corpses buried in mass graves in a forest named Ponar outside Vilnius, Lithuania. The Nazis wanted to conceal the crime by burning the bodies on mass pyres. The prisoners were shackled with chains and lived in a deep hole in the ground. Some of them discovered their families among the dead. And they had total certainty that once their job was done, they too would be killed. Yet at night, as Heath meticulously details, they began to dig a tunnel through a wall of their subterranean prison, using only their bare hands and spoons. On the night of April 15, 1944, after months of digging, they made their escape.

What could possibly motivate someone in these hellish circumstances to keep digging, night after night, hoping against hope? Heath combed through the testimonies left behind by the dozen escapees who made it out. Their mindset, if I can summarize it, was that they were going to be murdered, one way or another, and that it was better to die while making an attempt to undermine their captors. At the very least, they were exercising their own agency, their own remaining humanness, and in the very, very unlikely event that one of them could tell the story of what had happened in Ponar, they could sabotage the Nazis’ efforts to incinerate history.

Americans are not in the world of Sisyphus or in the world of those who face imminent death because of who they are. But these stories do tell us something about the way despair can clarify, producing a purer kind of hope shaped not by expediency but by a sense of what really matters. This is what Byung-Chul Han, a South Korean–born philosopher, calls a “dialectic of hope” in a new meditation on the subject, The Spirit of Hope, in which he sees despair as hope’s abysmal twin. “The higher hope soars, the deeper its roots,” Han writes. Just as despair can feel like stumbling through a pitch-black cave without an idea of where it ends, hopeful pessimism has the quality of being stranded on a deserted island yet bolstered by the ocean’s infinite blue.

For those who feel dread about America and the world, hopeful pessimism might seem like a thin string to grab on to, but it offers, I think, what might otherwise be called realism without requiring that one abandon the beauty of possibility. I like, too, that hopeful pessimism demands action, because there are no promises; it banishes wishful thinking. It’s the attitude of the philosopher Terry Eagleton, who began his 2015 book, Hope Without Optimism, by admitting that he saw himself as “one for whom the proverbial glass is not only half empty but almost certain to contain some foul-tasting, potentially lethal liquid.” And yet, he had to conclude, “there is hope as long as history lacks closure. If the past was different from the present, so may the future be.”

What's Your Reaction?

_Brain_light_Alamy.jpg?#)

![AI in elementary and middle schools [NAESP]](https://dangerouslyirrelevant.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/NAESP-Logo-Square-1.jpg)

![Trump’s FAA Shake-Up: DEI Gone, But Safety Questions Remain [Roundup]](https://viewfromthewing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/DALL·E-2024-01-24-12.35.35-A-wider-view-of-an-overworked-air-traffic-controller-in-a-control-tower-captured-from-a-side-angle.-The-controller-is-visibly-stressed-with-sweat-on.png?#)