After Trump’s Jan. 6 Pardons, Some Fear It Will Spur More Violence

"I worry that it will embolden people to engage in political violence"

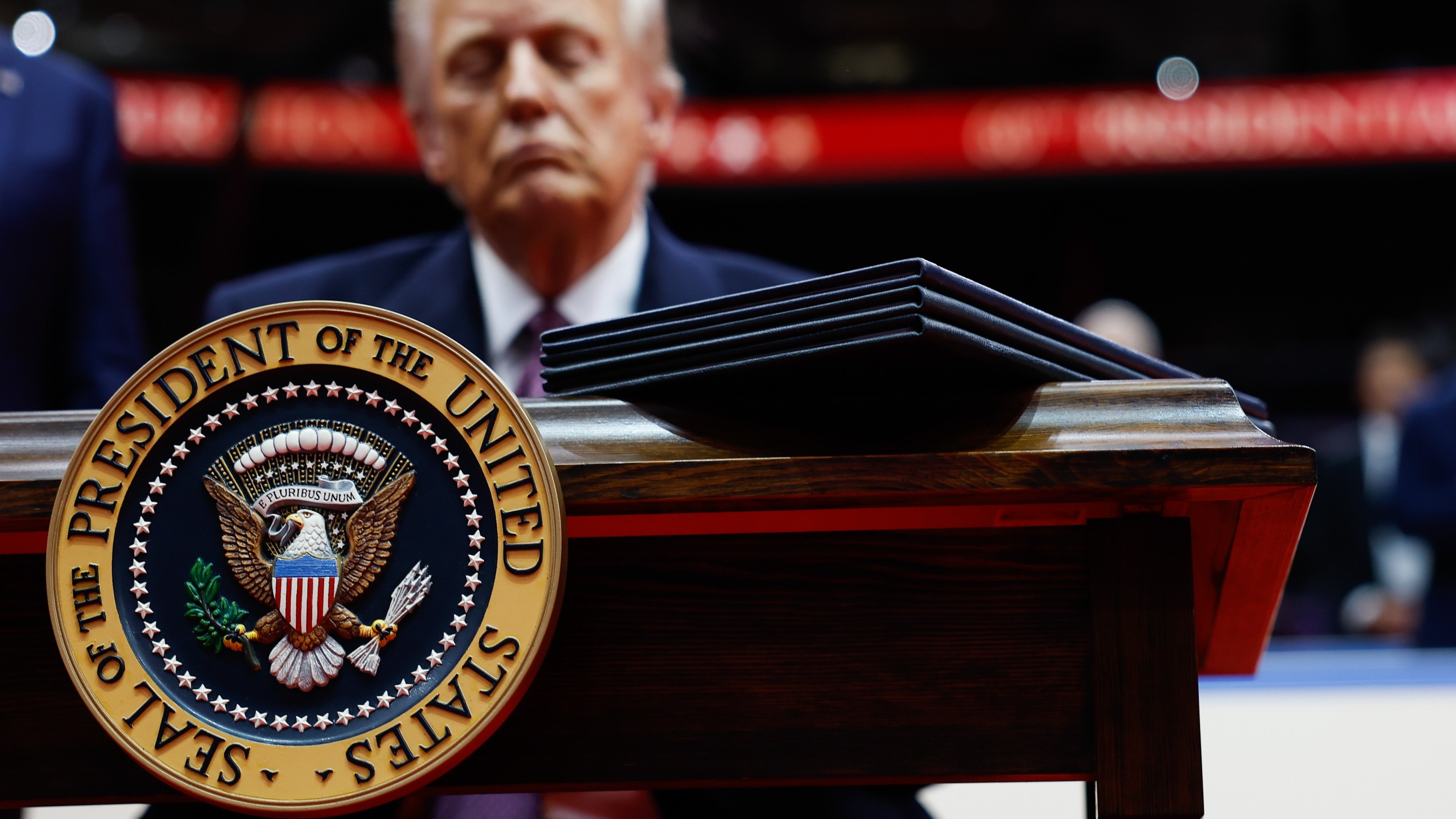

The first 24 hours of Donald Trump’s second term reflected what his supporters hoped for and his detractors feared: a willingness to follow through on some of his most radical and divisive ideas. That much was clear Monday night, when Trump made good on his pledge to exonerate the mob that stormed the Capitol on Jan. 6, 2021. [time-brightcove not-tgx=”true”]

Sitting behind the Resolute Desk in the Oval Office, the President pardoned or commuted nearly 1,600 of the defendants convicted or charged in connection with the attack, including those who carried out violent acts such as smashing windows and beating police officers. Among those reprieved were members of far-right extremist groups. Enrique Torrio, a Proud Boys leader, was sentenced to 22 years in prison after a jury of his peers found him guilty of seditious conspiracy. Stewart Rhodes, who founded the Oath Keepers, was serving an 18-year sentence on the same charges. By Tuesday afternoon, both men were free.

But Trump’s move amounts to more than fulfilling a campaign promise. Former prosecutors and legal experts fear it has far-reaching implications for the rule of law in the coming years, sending a message to Trump fanatics that they can commit crimes on the President’s behalf with impunity. “I worry that it will embolden people to engage in political violence, so long as they are acting in service to the leader,” says Barbara McQuade, a former U.S. Attorney. “I think this provides license for people to engage in that kind of vigilantism, and that’s a very dangerous place for a democracy to be.”

To the MAGA faithful, the pardons are the culmination of a four-year saga to rewrite the history of that day. Trump and his allies have sought to recast the insurrection as an act of patriotism, and the prosecution of rioters as a grave injustice. The President, who often calls the defendants “hostages,” vowed as a candidate to clear them of criminal charges; in April, he told TIME that he would “absolutely” consider pardoning all of them. Trump’s sweeping order comes close. He commuted the sentences of 14 individuals charged with seditious conspiracy and issued “a full, complete and unconditional pardon” for all the rest—providing some form of clemency to everyone charged or convicted for the attack.

To many, that’s a source of profound anxiety. Critics allege that Trump has often said just enough for extremists to think they have his blessing. After a deadly white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Va., he said there were “good people on both sides.” During a 2020 debate with former President Joe Biden, he told members of the Proud Boys to “stand back and stand by.” Scholars of the far right see the pardons as sending a conspicuous signal. “I think this is the most concrete instance of Trump conferring material benefits to people who are willing to serve as pro-MAGA vigilantes and who operate in these militia groups,” says David Noll, a Rutgers law professor and the co-author of Vigilante Nation. “I think the message they’ll hear is that Trump is one of them—and Trump has their back.”

After the Jan. 6 rampage, fears of violence spurred prominent anti-Trump lawmakers including Mitt Romney, Liz Cheney, and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez to spend tens of thousands of dollars in campaign funds on private security details. Trump “has quite literally released people who we know are ready, willing, and able to target Congress as it performs its constitutional functions,” says Noll.

McQuade suspects Trump’s pardons could “cause a chilling effect” on everyone from legislators and federal bureaucrats to journalists and private citizens. “If they are worried that Donald Trump’s rhetoric will unleash political violence against them and will then be pardoned,” she says, “I could see people engaging in self-censorship to avoid becoming a target of political violence.” That may have already happened. Romney told the journalist McKay Coppins that a Republican congressman confided in him that he chose not to vote for Trump’s second impeachment after the Capitol riot for fear of his family’s safety.

The aftereffects may be most distressing to those directly impacted by the Jan. 6 assault. Former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi—who was rushed out of the House chamber after rioters breached the Capitol and whose husband was later battered with a hammer in a separate politically-motivated attack—called Trump’s order “shameful” and “an outrageous insult to our justice system.” The brother of Capitol Police officer Brian Sicknick, who died from a stroke the day after the attack, told ABC News the pardons were an affront. “The man doesn’t understand [the] pain or suffering of others. He can’t comprehend anyone else’s feelings,” Craig Sicknick said. “We now have no rule of law.”

For some of the President’s fiercest allies, though, Trump’s pardons reflect yet another triumph that stems from the power the American people have handed him. “I don’t give a damn what Democrats say about Trump’s Jan. 6 pardons and commutations,” says Mike Davis, who founded the conservative Article III Project. “We won, they lost. F**k you.”

What's Your Reaction?