Vittorio De Sica’s Collective Actions

Illustrations by Michelle Perez.The inner life of man is constituted by the fact that man relates himself to his species, to his mode of being. […] He can put himself in the place of another precisely because his species, his essential mode of being—not only his individuality—is an object of thought to him. —Ludwig FeuerbachThere are only individuals. —Friedrich NietzscheThe idea of the individual haunts much of the writing on Vittorio De Sica’s films. No other critic has played a greater role in shaping how we speak about them than André Bazin, who remarked that De Sica’s postwar masterpiece Bicycle Thieves (1948) allowed its actors “first of all to exist for their own sakes, freely … loving them in their singular individuality.”1 This line has cast a long shadow over the perception of De Sica’s neorealist work and the manner in which it is mythologized. Typically described, De Sica’s films are said to follow individuals cast aside by a social system incapable of providing for them—this is true of a number of his most famous films, among them Bicycle Thieves and Umberto D. (1952). Even those titles suggest individualization, even more so when the former—Ladri di biciclette, in the original Italian—was mistranslated as “The Bicycle Thief” upon its initial international release. In French, too, at the time of Bazin’s writing, this title was rendered in the singular, Le Voleur de bicyclette. The decision between “The Bicycle Thief” and “Bicycle Thieves”—the film is now distributed under the latter, corrected title—is more than just a question of linguistic fidelity. For one, the singularity of the former leaves ambiguous which character it’s meant to describe: does it refer to the young man whose theft of Ricci’s bicycle sets the film into motion, or is it Ricci himself, whose later theft of a bike brings the action to a close? Furthermore, the stakes of this ambiguity run deeper than a mere concern for narrative clarity; they are central to De Sica’s entire conception of character and to the moral universe to which his films belong. Ricci’s good fortune to receive a job pasting posters in the streets of Rome has nothing to do with his skills, but is a pure stroke of luck, one that might have fallen on any of the other men in the crowd waiting for work. His pursuit of the first thief fails to turn up the missing bicycle, and the success of this theft owes as much to chance as Ricci’s failure in the film’s finale. That he finally succumbs to crime is not, for De Sica, the mark of a personal failure so much as it points to circumstances that would drive anyone to steal. Of all of De Sica’s films, Bicycle Thieves is the one most devoted to a kind of Dostoyevskyian morality: crime is never truly particular to the individual, but is always transferrable and ultimately social in character.What lesson might we draw from this example? First, that in De Sica’s films, no story is ever truly individual—no matter how personal, no matter how intimate, it’s always something that can and has happened to others. Hospitalized after getting evicted from his apartment, Umberto D. is filmed as one among many patients seated in a row at the ward. Giuseppe and Pasquale, the child protagonists of Shoeshine (1946), are just two of the hundreds of inmates at the juvenile detention center. This remains true across genres and subjects. As Jennifer Jones and Montgomery Clift admit their love for each other in their first encounter at the train station in Indiscretion of an American Wife (also known as Terminal Station, 1953), we can spot another couple at a table just behind them engaged in their own hushed conversation. Even this, which should be their most personal and private moment, is multiplied. No story is truly one’s own. When he writes about De Sica, Bazin will sometimes suggest that his films give the impression they might have picked anyone off the street to follow. This is true, but only to the extent that the plight of all the potential candidates, so far as De Sica is concerned, leads to the same conclusion.Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946).In the individual, De Sica sees the fate of the species. It’s here that we can most clearly draw the line distinguishing him from Roberto Rossellini, who is always concerned with the absolutely particular. Germany, Year Zero (1948) may begin as an allegory for the fate of the country after the war, as its title announces, but the last reel completely severs its characters from this responsibility to represent the nation.2 Over the course of the film, the young boy disentangles himself bit by bit from the groups that might capture him in some way: his family, whose neglect eventually leads him to fratricide; the other young boys, perhaps too mature to take him seriously; his teacher, whose interest in him turns out to be predatory. The design of this film—we might say the same of Stromboli (1950) and Europe ’51 (1952)—compels the character to solitude. For the most part, Rossellin

Illustrations by Michelle Perez.

The inner life of man is constituted by the fact that man relates himself to his species, to his mode of being. […] He can put himself in the place of another precisely because his species, his essential mode of being—not only his individuality—is an object of thought to him.

—Ludwig Feuerbach

There are only individuals.

—Friedrich Nietzsche

The idea of the individual haunts much of the writing on Vittorio De Sica’s films. No other critic has played a greater role in shaping how we speak about them than André Bazin, who remarked that De Sica’s postwar masterpiece Bicycle Thieves (1948) allowed its actors “first of all to exist for their own sakes, freely … loving them in their singular individuality.”1 This line has cast a long shadow over the perception of De Sica’s neorealist work and the manner in which it is mythologized. Typically described, De Sica’s films are said to follow individuals cast aside by a social system incapable of providing for them—this is true of a number of his most famous films, among them Bicycle Thieves and Umberto D. (1952). Even those titles suggest individualization, even more so when the former—Ladri di biciclette, in the original Italian—was mistranslated as “The Bicycle Thief” upon its initial international release. In French, too, at the time of Bazin’s writing, this title was rendered in the singular, Le Voleur de bicyclette.

The decision between “The Bicycle Thief” and “Bicycle Thieves”—the film is now distributed under the latter, corrected title—is more than just a question of linguistic fidelity. For one, the singularity of the former leaves ambiguous which character it’s meant to describe: does it refer to the young man whose theft of Ricci’s bicycle sets the film into motion, or is it Ricci himself, whose later theft of a bike brings the action to a close? Furthermore, the stakes of this ambiguity run deeper than a mere concern for narrative clarity; they are central to De Sica’s entire conception of character and to the moral universe to which his films belong. Ricci’s good fortune to receive a job pasting posters in the streets of Rome has nothing to do with his skills, but is a pure stroke of luck, one that might have fallen on any of the other men in the crowd waiting for work. His pursuit of the first thief fails to turn up the missing bicycle, and the success of this theft owes as much to chance as Ricci’s failure in the film’s finale. That he finally succumbs to crime is not, for De Sica, the mark of a personal failure so much as it points to circumstances that would drive anyone to steal. Of all of De Sica’s films, Bicycle Thieves is the one most devoted to a kind of Dostoyevskyian morality: crime is never truly particular to the individual, but is always transferrable and ultimately social in character.

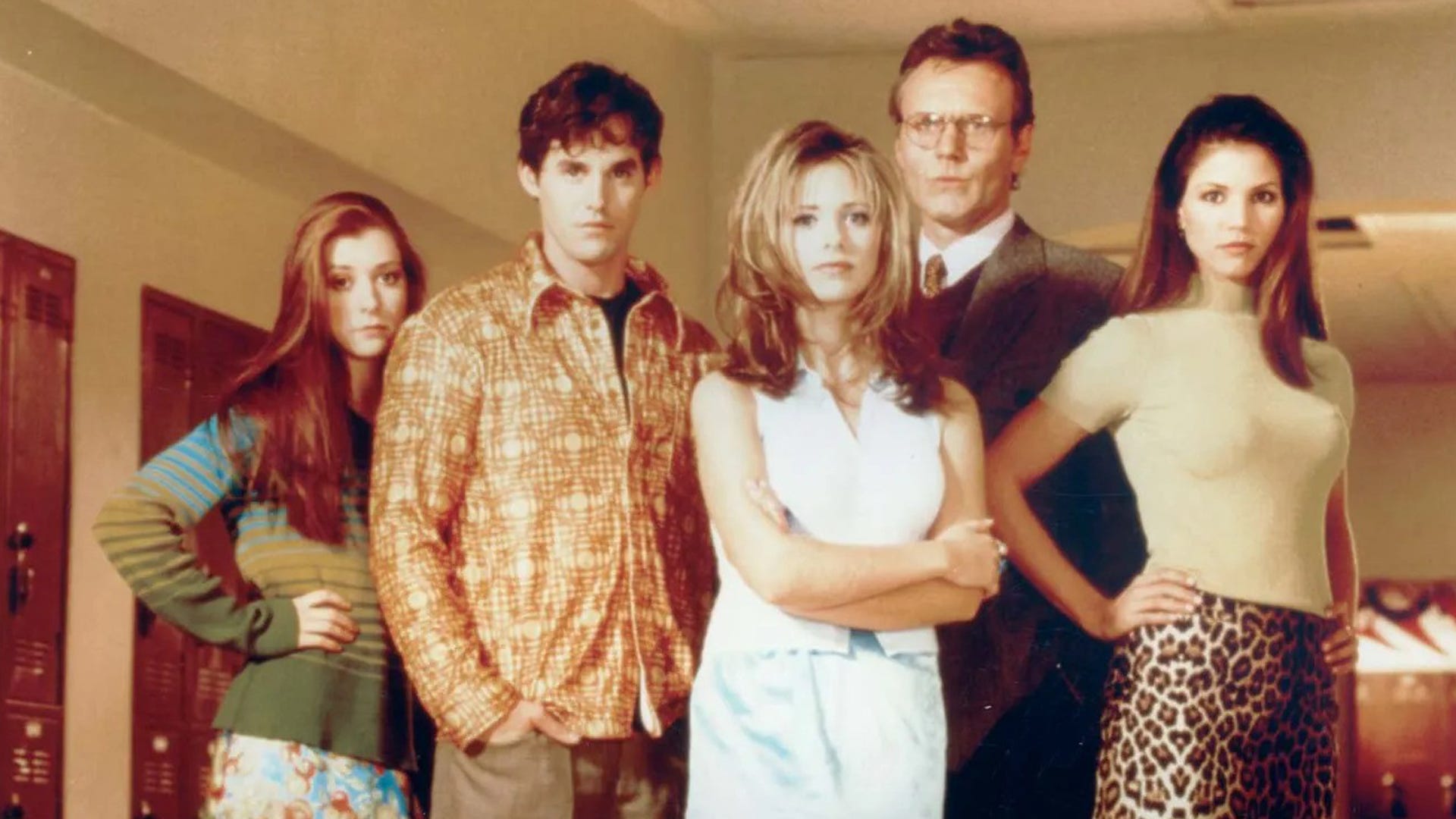

What lesson might we draw from this example? First, that in De Sica’s films, no story is ever truly individual—no matter how personal, no matter how intimate, it’s always something that can and has happened to others. Hospitalized after getting evicted from his apartment, Umberto D. is filmed as one among many patients seated in a row at the ward. Giuseppe and Pasquale, the child protagonists of Shoeshine (1946), are just two of the hundreds of inmates at the juvenile detention center. This remains true across genres and subjects. As Jennifer Jones and Montgomery Clift admit their love for each other in their first encounter at the train station in Indiscretion of an American Wife (also known as Terminal Station, 1953), we can spot another couple at a table just behind them engaged in their own hushed conversation. Even this, which should be their most personal and private moment, is multiplied. No story is truly one’s own. When he writes about De Sica, Bazin will sometimes suggest that his films give the impression they might have picked anyone off the street to follow. This is true, but only to the extent that the plight of all the potential candidates, so far as De Sica is concerned, leads to the same conclusion.

Shoeshine (Vittorio De Sica, 1946).

In the individual, De Sica sees the fate of the species. It’s here that we can most clearly draw the line distinguishing him from Roberto Rossellini, who is always concerned with the absolutely particular. Germany, Year Zero (1948) may begin as an allegory for the fate of the country after the war, as its title announces, but the last reel completely severs its characters from this responsibility to represent the nation.2 Over the course of the film, the young boy disentangles himself bit by bit from the groups that might capture him in some way: his family, whose neglect eventually leads him to fratricide; the other young boys, perhaps too mature to take him seriously; his teacher, whose interest in him turns out to be predatory. The design of this film—we might say the same of Stromboli (1950) and Europe ’51 (1952)—compels the character to solitude. For the most part, Rossellini doesn’t film crowds. He has an idea of the nation (Paisan, 1946; Stromboli), of class (The Taking of Power by Louis XIV, 1966) or of a political faction or sect (Socrates, 1971; The Messiah, 1975), but the crowd is, in large part, something to be avoided in his films.3 Particularly in his neorealist period, Rossellini searches for the single gesture of the performer capable of disclosing what is most urgent to the times of the film’s making.

De Sica’s films never arrive at this degree of particularity, nor do they seem to seek it. Characters in his films are never individual so much as they are typical. Bazin, whose writing on De Sica deservedly remains canonical, claimed that an understanding of De Sica’s directorial work is inseparable from an understanding of his main screenwriting collaborator, Cesare Zavattini.4 But Bazin does not seem to have had the fortune to view De Sica’s films prior to The Children Are Watching Us (1944), his first complete collaboration with Zavattini.5

De Sica got his start in popular “white telephone” comedies—so called for the middle-class status symbol therein, a step up from the widely available black Bakelite model. Most of his earliest films as a director were in the same mold, and he often also starred as the romantic lead. Red Roses (1940), his first feature, is an amusing remarriage comedy modeled partly on Leo McCarey’s hit The Awful Truth (1937), in which a philandering husband (De Sica) concocts a scheme to convince his wife to fall in love with him again.6 Though the first act of Maddalena, Zero for Conduct (1940) borrows from the 1933 Jean Vigo film of the same name, it transports Vigo’s anarchistic spirit to a more classically farcical upper-class setting once De Sica’s character finally arrives at the end of the second reel. As in his later films, children are already wiser than adults, who are foolish, juvenile, and too caught up in romantic intrigue.

Teresa Venerdì (Vittorio De Sica, 1941).

More telling is Teresa Venerdì (1941), his last romantic comedy until the mid-’50s and his first great film. When it was belatedly released in the United States after the war, Anna Magani had become world famous for her role in Rossellini’s Rome, Open City (1945) and thus received top billing with De Sica, though her role is in fact a supporting one, as one of three women vying for his romantic affection. More than in his previous films, Teresa Venerdì begins to figure the themes later enlarged by De Sica’s following four films. Here, as in elsewhere, characters travel in packs: creditors, students, administrators, nurses. Like Jacques Tati, De Sica is one of those filmmakers who sees everything in types and whose sense of humor derives from this classification.

De Sica’s neorealist period, beginning with The Children Are Watching Us, breaks with the subject and tone of these earlier comedies, but not in overall outlook and perspective. This is perhaps most apparent in Miracle in Milan (1951), done in the burlesque style of American Depression–era comedy. But even those more serious in tone—The Gates of Heaven (1945), Shoeshine, Bicycle Thieves, Umberto D., and The Roof (1956)—maintain this view of type, manifested in their concern for crowds. What does it mean to film a crowd? We know from the American cinema, for example the films of James Whale (Frankenstein, 1931), Fritz Lang (Fury, 1936), King Vidor (The Crowd, 1928), or Frank Capra (Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, 1939), what constitutes a mob: noisy, angry, unthinking. Conversely, the early films of Sergei Eisenstein show the masses in the process of amalgamating into a class.

Yet crowds in De Sica’s films fit into neither mold. Umberto participates in a demonstration calling for pension reform, but it’s quickly and easily dispersed by the Italian Carabinieri. Despite the fact that so many of his characters find themselves among others who share their plight, few of them ever manage to form any lasting sort of collectivity. Ricci does not enjoy the company of other workers. When we meet him at the start of Bicycle Thieves, he’s sitting far from the group gathered at the factory gate, unaware that his name has been called until another man runs over to bring him the news. Despite his own lifelong allegiance to the Italian Communist Party, the films of De Sica’s neorealist period tend to reflect a Christian existentialist outlook on politics, less interested in collective action than in characters confronting their lack of individual agency over their lives. Yet despite this, they are pluralized by the film’s mise-en-scène: none of his characters are alone in struggle, but their struggle is, for the most part, a lonely one.

The Roof (Vittorio De Sica, 1956).

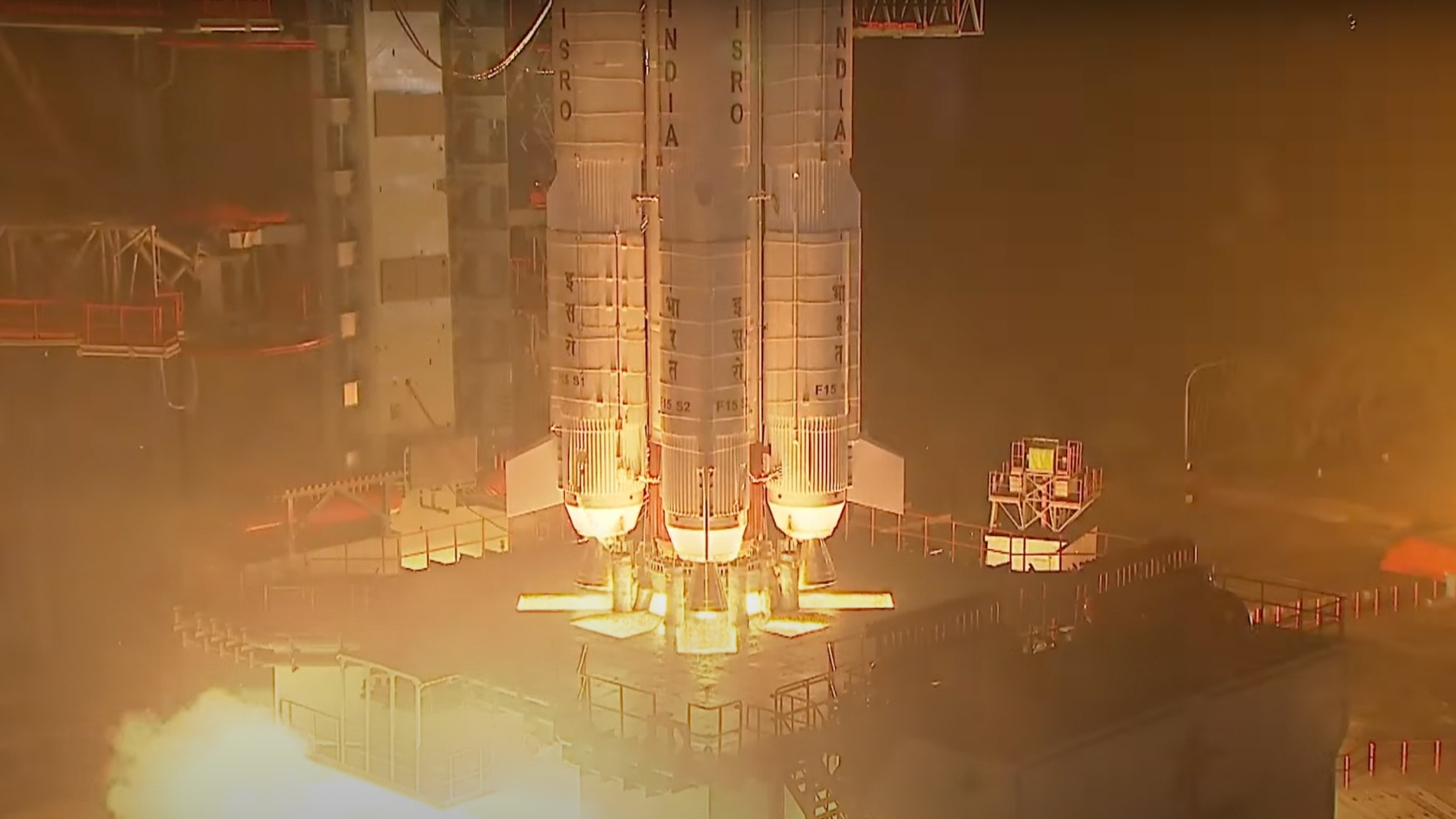

The Roof is the last of De Sica’s films that could be plausibly considered neorealist, and it’s telling that it’s also the first one to depict collective solutions. He often omitted it when discussing his career in later interviews, dating the end of his neorealist period to Umberto D. We can surmise that his reticence to mention it is due in no small part to the film’s critical failure, liked more than his preceding film, The Gold of Naples (1954), but less passionately than his previous neorealist works. Yet it’s the final film in De Sica’s filmography to subscribe to the usual characteristics of neorealist films: shot on location in Rome, led in large part by nonprofessional actors (though its leading lady, Gabriella Pallotta, would continue to act in films for another two decades), focusing on subjects borne from everyday suffering of working people. That the film resolves itself through collective action emerges naturally from its subject.

A young bricklayer, Natale, and his wife, Luisa, newly married, struggle to find affordable housing until they discover the law protects any dwelling with a roof from being torn down, meaning they can build their own lodging on the outskirts of Rome provided it is completed before the police arrive to tear it down. In De Sica’s previous films, characters seldom rely on each other for support. Ricci’s shame keeps him from asking his wife for help in Bicycle Thieves. Umberto lacks family and friends who could take him in after he is evicted from his apartment. Here, for the first time, the characters both seek and receive help. Despite the violent disagreements between Natale and his brother-in-law, Cesare, in the film’s first half, the pair reconcile to complete the shelter with the help of others living in squats nearby.

This resolution marks a departure from the perspective taken in De Sica’s previous films. The opening to The Children Are Watching Us mocks the pretenses that prevent collective solutions: a discussion held among the members of the condominium over whether the elevator should go up and down satirizes the inability of collectives to take action to solve real problems, tangling themselves up in increasingly stupid ones. The selfishness that prevents collaboration between the tenants is presented by De Sica as a refusal of one’s duty to others, a point he underscores through the mother’s unfaithfulness to the father in the second half of the film.

Miracle in Milan (Vittorio De Sica, 1951).

Miracle in Milan comes the closest to offering an image of a collective, and is closely aligned with The Roof in subject, as both are concerned with homeless populations founding a village of their own on unused land. Yet this earlier film retains its focus on a singular character, Totò, who comes to personify the communal spirit. This is what fundamentally distinguishes the community of Miracle from the one in The Roof: the latter’s problems are not resolved by reasons of fate or through miracles, but through a chosen, mutually recognized alliance of interests. They are the first of De Sica’s protagonists to see their problems solved together, making theirs the only of his neorealist films with an uplifting ending.

After The Roof, the style of De Sica’s films changes almost completely. He continued to collaborate with Zavattini, who wrote Two Women (1960) and Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow (1963), the two best-loved of De Sica’s films in the post-neorealist period, as well as his penultimate feature, A Brief Vacation (1973). And yet these films more closely resemble De Sica’s earlier upper-class comedies and bear little obvious resemblance to the neorealist films. Yet throughout his life, he spoke most highly of his neorealist work—Umberto D., dedicated to his father, remained his favorite of all his films. Today, these films continue to pose problems of social welfare, as urgently felt now as in the postwar period.

Rare are the filmmakers who can capture what is uninviting about modern life in a single image, or who can render visible the experience of extreme alienation that comes from owning nothing. When I think of De Sica, I think of the shots from Ricci’s perspective as he searches for the bicycle thief. Few point-of-view shots in cinema come across as impersonally as these, so powerfully evoking the sense that one doesn't and cannot belong.

Further reading: “Mike Leigh’s Humanist Gestures” by Sam Bodrojan.

- André Bazin, “De Sica: Metteur en scène”, in What is Cinema Volume 2, trans. Hugh Gray (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1972), 69. ↩

- This is why attempts to replicate it in other contexts, like Carlos Saura did for Spain with Cría Cuervos (1976), come up a bit short. The dramatic force of that film is entirely allegorical. It lacks the same documentary sense of danger that characterizes the best of Rossellini’s early neorealist films. ↩

- The major exception to this is, of course, the finale to Journey to Italy (1954), in which a crowd pulls George Sanders and Ingrid Bergman apart from each other. Yet this exception is revealing, providing the background for the transcendent reunion of the two lovers in spite of the material and psychic forces driving them apart in the preceding scenes. ↩

- I have used the translations by Hugh Gray published by UC Press in 1972. A newer translation of these essays, presented alongside essays never previously translated from the fourth volume of Bazin’s Qu’est-ce que le cinéma?, was completed by Bert Cardullo and published as André Bazin and Italian Neorealism (Continuum, 2011). ↩

- Zavattini received a writing credit on Teresa Venerdì, though his biographer David Brancaleone suggests this mostly entailed rewriting the dialogue of the original script. See Cesare Zavattini’s Neo-realism and the Afterlife of an Idea: An Intellectual Biography (Bloomsbury, 2021), 57. ↩

- Giuseppe Amato, who later served as a producer on several of De Sica’s neorealist films, is listed as a codirector on this film, though his role appears to be limited to manning the camera while De Sica is on screen. ↩