The Marketing of High School Athletes: A Rolling Tide

The expansion of “name, image, and likeness” rules could be both a boon and a burden to secondary schools The post The Marketing of High School Athletes: A Rolling Tide appeared first on Education Next.

Stanford University economics professor Roger Noll has had a front-row seat on sweeping changes in sports throughout his career. In the 1990s he was a witness for National Football League players in their antitrust case against the league. Then, in 2014, he was the plaintiff’s key expert in O’Bannon vs. NCAA, the antitrust class-action suit that eventually led the National Collegiate Athletic Association to allow college athletes to make money and retain their eligibility to play. Now Noll believes another significant transition is on the near horizon.

“Think all this talk about college sports is big?” Noll said from his Stanford office. “There’s a whole other world 10 times as big as college athletics that’s about to face serious issues—high school sports. There’s a three- or four-year lag, but it’s coming.”

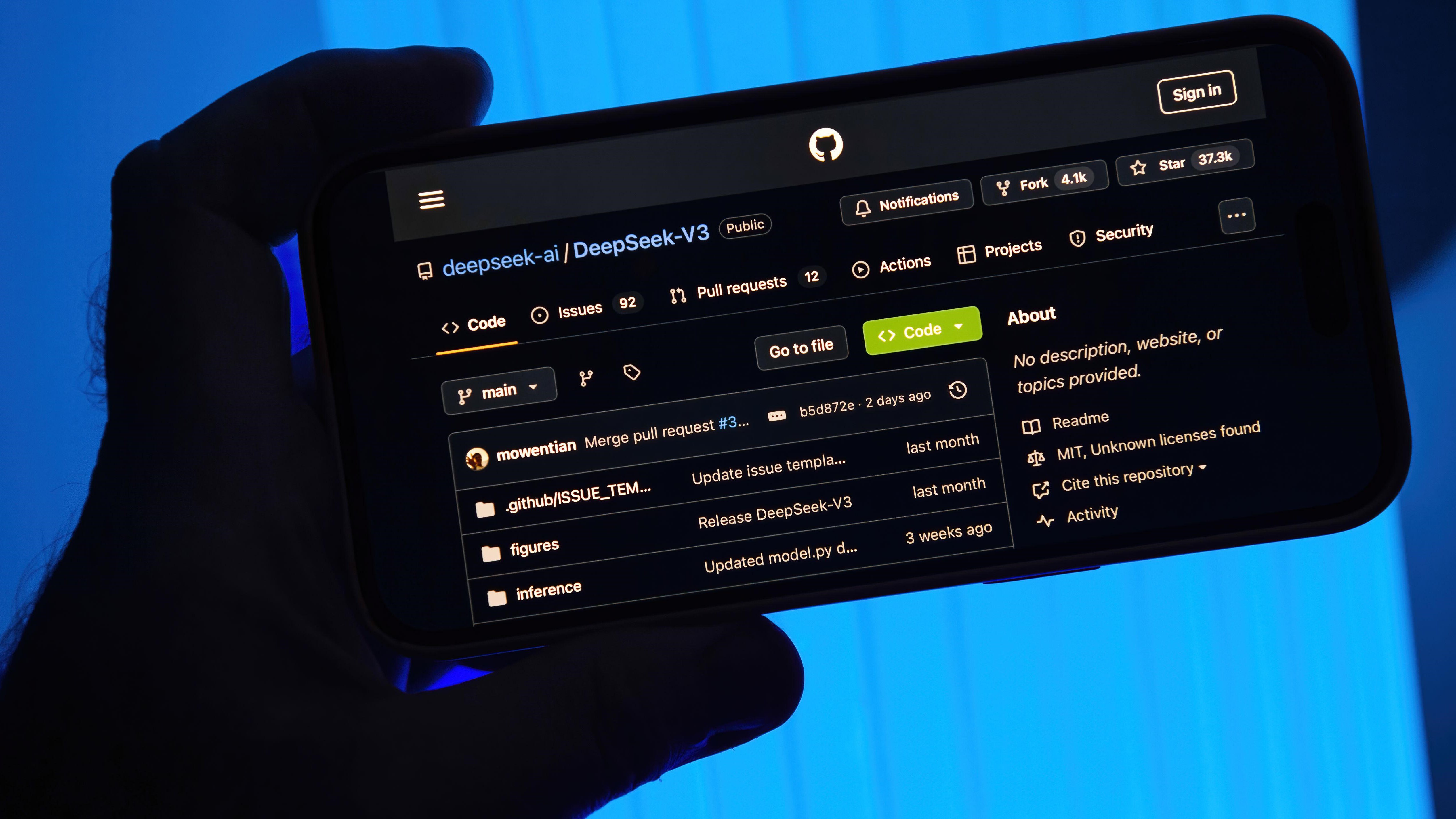

In July 2021, for the first time, the NCAA gave college and some high school athletes permission to make money from their “name, image and likeness” (NIL). Athletes in a wide range of sports immediately started signing marketing contracts with sponsors. The deals included advertisements for local businesses, compensation for player trading cards, and partnerships with national companies like Nike, Gatorade, Dr. Pepper, and Mercedes Benz. NIL has transformed the college sports landscape, and the revenue has exceeded even optimistic expectations. The marketing company Opendorse estimates that college athletes’ NIL earnings will grow from $917 million in 2021 to $2.5 billion by 2026. The new money has changed the way teams and athletes relate to their schools, fueled an increase in transfers to athletic-powerhouse universities, and destroyed any remnant of the notion that college sports are not professional—that is, commercial.

High school NIL has drawn much less publicity. But after university administrators and public officials underestimated the impact of the new rules in the college arena, high schools would be naive to ignore the issues that could arise with an influx of money in coming years. The number of student athletes who sign marketing deals will increase, which will affect where they choose to attend high school and potentially disrupt their academic experiences. Financial pressure will force schools to make tough decisions on how much time and money they are willing to invest in athletics and whether they want to stay competitive as the marketplace gets more complicated and expensive.

For many students, sports are an important part of the high school experience, and they create deeply rooted traditions in communities around the country. Athletes benefit from the accountability, the relationships, and the physical activity that come with participating in a sport. But NIL could shake up the scene in ways no one saw coming. Coaches, athletic directors, and principals would do well to stay on top of both the pitfalls and the opportunities that could soon arise.

Currently, 40 states allow high school athletes to accept some form of compensation. William Carter, a top NIL consultant who teaches courses on sports entrepreneurship at the University of Vermont’s Grossman School of Business, estimates that only about 1 percent of high school students have made NIL deals so far.

“As of fall 2024, it’s not having a big impact,” Carter said. “So the question is why. It affects millions of high school athletes. High school students have the right to pursue NIL in over 70 percent of the country. . . . Until players learn more, it’s going to be at a low hum. But I do think that day will come. It will absolutely come. It will just take time to get there.”

When the NIL era began, many observers assumed that such deals would accrue only to the most high-profile players—the football quarterbacks. On the contrary, NIL has spread to men and women athletes in all sports. According to Carter, more than 20 percent of Division I athletes have signed NIL deals. “If you talked to high school students, they would say, ‘I’m not a star. This is not available to me,’” Carter said. Local businesses “think that the athlete has to have 500,000 to a million social media followers. That is patently false. A soccer player with 5,000 followers can do a deal with a local pizza place” and drive revenue for the business. And NIL has even started to infiltrate middle schools. As the Washington Post recently reported, at least five players on the powerhouse John Hayden Johnson Middle School football team in Washington, D.C., have secured NIL deals.

Charles Stanfield of Inspiration Athlete Marketing has represented NFL and NBA players, but in recent years his business has shifted more toward college athletes. He represents two standout quarterbacks of the 2024 college football season—Cam Ward, who plays for the University of Miami, and Jalen Milroe of the University of Alabama—and he is bullish on the potential of high school students to earn NIL money as well.

“A lot of people got it wrong back in ’21 when NIL started,” Stanfield said. “I sat in meetings with Nike executives in 2011 and heard firsthand their shift in approach. They used to focus on parents, assuming they’d bring their children to Dick’s Sporting Goods to buy shoes. In part because of social media, that’s flipped. They want to reach the 10-year-old and have them drag their parents to the store. . . . Now the shoe companies are all about speed and youth. They don’t want the ‘old’ quarterback. They want college athletes. High school athletes will be next.”

Nike jumped into the high school athletes pool when they signed soccer players Alyssa and Gisele Thompson in May 2022. The company went on to make deals with high school track and field athletes and basketball players, including Bronny James, now with the Los Angeles Lakers, and JuJu Watkins, who went on to star at the University of Southern California.

The marketability of young athletes does not necessarily worry high school administrators. Many have no objection to athletes profiting off their own popularity. The fear for high schools is what’s happening in college—NIL is now the primary recruiting tool for football and basketball. A similar dynamic could trickle down to high school and exacerbate a trend in player transfers that is already changing the balance of power nationwide.

“One of the biggest shifts in amateur sports is athletes leaving public schools for private,” Noll said. “Colleges have rules for recruiting. I’m not sure high schools are ready to regulate that process, especially now that players can earn money. Expect a much higher variance in the quality of decisions high school administrators make compared to the college level.”

The Growing Influence of Collectives

After the NCAA gave the green light for college players to become paid endorsers and earn money through marketing, college football boosters started forming NIL collectives—independent organizations that raise money to help recruit star athletes to a particular university. While collectives technically exist within the NIL framework, the contracts they offer are designed to pay for play, not to use the athletes’ name, image, and likeness for marketing purposes. According to the New York Times, 80 percent of college-level NIL payments come through a collective.

While the collective model is allowed at the college level, state authorities do not want it to filter down to lower levels. Georgia recently revised its policy to clarify the kinds of deals it does and does not permit at the high school level: “No student athlete may be a member of nor receive compensation or any other benefit from a Collective or NIL Club.”

States face an enormous challenge to maintain the ban on high school collectives. “Even though this will continue to be tested,” Carter said, collectives “feel to me like truly a red line. The state athletic associations will die on this hill. They are not going to allow this.”

Karissa Niehoff, executive director of the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), is wary of new players in the NIL marketplace. “Collectives are disturbing,” Niehoff said. “They’re popping up left and right. . . . They’re outside of the school. And there are a number of them now that profess to be the best at advising parents and getting kids connected, developing the potential of their NIL and assuring them a safe, positive experience. One of the latest things that we’re seeing is what I’ll call the booster club imposter, where anybody can join and name the team that you want to support, offer some money. You can name a student athlete that you want to support.”

High school NIL collectives are currently ill-defined and not monitored for quality, Niehoff said. The federation is working to ensure any organization offering to pay athletes follows state and national rules, and it has had to ask several sites to take down photos of high school players wearing team jerseys, which is strictly prohibited in all states. Niehoff is also concerned that school supporters will mimic colleges and attempt to use NIL for recruiting.

The federation is watching how NIL is influencing the transfer activity of student athletes, Niehoff said. “We’re seeing our state associations dealing with literally hundreds of transfer waiver requests. California had 17,000 transfers last year. . . . You’re seeing kids that want to move schools, following coaches, a lot of trying to get around the rules. Some of it is NIL induced.”

Vincent Minjares, project manager for the Sports and Society Program at the Aspen Institute, noted the downstream ramifications of recruiting. “Suburban private schools are consolidating resources,” Minjares said. They have “nicer facilities, they’re more likely to pay a full-time coach, have a strength and conditioning coach, a full-time athletic trainer.” Schools with winning programs begin to dominate even more as they pull students from other schools. “We’re seeing this inability to keep up with the Joneses. It’s creating a huge void for smaller public schools, schools that don’t have massive budgets,” he said.

For high schools that can’t retain athletes, Minjares has observed, shutting down programs can be a more viable option than trying to compete with wealthier schools. That means students who want to participate in sports, including non-elite athletes, lose that opportunity. Some families will add significant commuting time or move to another community just so their student will have a chance to play.

This situation also raises equity issues. “If alumni are donating to winning teams in suburban environments,” Minjares said, “if sponsors are focused on the elite players who have been consolidated in the suburban, affluent environments, then ultimately we are leaving urban, working class, rural, and predominantly Black and brown kids to the wayside. They are not getting systemic investment in the same way.”

Some schools put a particularly strong emphasis on recruiting student athletes. For example, IMG Academy, a boarding school in Bradenton, Florida, focuses on training young athletes and recruits its students from across the country. Elsewhere, a handful of local high schools—often private—have developed programs that dominate their divisions. As these programs become more successful, they attract coverage on networks like ESPN, and their student athletes amass social media followers. If NIL activity continues to increase in high school, students will be further incentivized to choose schools with outstanding sports programs.

“While a collective makes sense in the college context,” Minjares said, “we do not want recruiting to become a norm in high school. We want people to attend school for the purpose of getting their education, making friends, and playing sports as an avenue for enhancing that experience.” The introduction of collectives, he said, has the potential to “exponentially distort” the way student athletes choose a high school.

While the NFHS and state high school athletic associations are holding a firm line against collectives, their legal right to do so could be challenged. At the college level, the courts have repeatedly ruled against the NCAA and other entities that have attempted to restrict athletes from receiving compensation in any form.

The states that currently don’t allow any high school NIL deals will likely face legal challenges that force them to change their rules. Last summer the family of Grimsley High School quarterback Faizon Brandon, North Carolina’s top high school prospect, sued the state for what they asserted was a missed earning opportunity. In October, a Wake County Superior Court judge ruled that the NIL prohibition, which only applied to public schools, was illegal. North Carolina is expected to rewrite its rules to allow NIL for all high school student athletes.

“High school sports associations are non-governmental actors,” said Noah Henderson, a sports marketing professor at the University of Illinois Chicago. “For lack of a more precise term, they’re trade organizations. They don’t have any regulatory power.” If a school tries to constrain the market, it’s opening itself up for potential antitrust litigation, he said. “You’re essentially a price-fixing machine.”

The more critical challenge for state high school athletic associations is maintaining the ban on collectives. Because of the impact of collectives on student athlete transfers, courts might consider them a threat to the public school system.

“I think the courts will side with the state high school athletic associations” on the collectives issue, Carter said. “It’s not just about fair play, but it has to do with the structure of a public school system. You can’t have kids getting up and playing 40 miles away.”

State high school athletic associations, however, are not well equipped to fight legal battles to protect their rules. “High schools don’t have the resources colleges have,” Roger Noll said. “That’s why this is going to be so chaotic in the coming years.” Considering that the NCAA and colleges are consistently losing in the courts, state rules for high schools will be vulnerable to challenges.

Return on Investment

Quincy Avery, who has been working with young football players since 2011, is considered one of the top quarterback trainers in the nation. His client list includes NFL and college starters, and his organization, QB Takeover, provides individual and group lessons to more than 100 high school and middle school players.

Avery described a feeding frenzy around high school NIL. “Everyone starting at QB in a state with legal high school NIL thinks they should be getting paid,” he said. “They ask for help getting representation. I tell them, ‘You’re not even good enough to get a college scholarship. You need to focus on getting better, not getting paid.’”

Signing up for lessons with an NFL quarterback coach isn’t cheap, and Avery has increasingly had to deal with parents’ unrealistic expectations about NIL. “They want a return on investment,” he said. “They’re spending all this money from the time their kid is 10 years old, and they read about a star high school quarterback who’s making seven figures and think that their son can do the same thing. They can’t. I call it ‘parent goggles.’ Hard to see clearly when it’s your own kid.”

Across the country parents are spending more than ever on athletic training. The Aspen Institute estimates that families spent an average of $883 per child on youth sports in 2022. Costs associated with travel and personal coaching can increase dramatically for elite athletes.

Another development has reshaped amateur sports in recent years—an influx of private equity into the companies that run youth programs in sports such as soccer, baseball, and flag football. Josh Harris and David Blitzer, co-owners of the NFL’s Washington Commanders, the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers, and the NHL’s New Jersey Devils, led a private equity group in heavily investing in youth sports companies. They formed Unrivaled Sports last May to oversee all their youth sports assets, including ownership of the Cooperstown All-Star Baseball Village, Ripken Baseball, the action sports company We are Camp, and the Forever Sports Lawn Complex at the Pro Football Hall of Fame Village. Other groups have infused capital into travel leagues and multisport facilities around the nation.

“Private equity comes into these spaces with the intention of either selling [these companies] later at a profit or simply making lots and lots of money,” Minjares said. “If they improve the experience and raise the costs, now you just raised the cost of youth sports” for families. Such a cost escalation would result in private equity effectively competing “for the dollars of an increasingly smaller pool of parents and families. The consolidation of talent would then filter into high school sports as well.”

For parents who want a way to offset the training costs with NIL income, there’s no shortage of people who claim they can find the money. “Kids are getting calls from supposed marketing agents that my team and I have never heard of,” Avery said. “It’s wild out there. People are trying to take advantage of players who really have nothing to market.”

Corey Staniscia is a former political lobbyist who helped author Florida’s college sports NIL law in 2019 while working as an aide in the state house of representatives. He now runs the Furman Street NIL Collective, which provides funds for University of South Florida athletes.

“Bad actors in this space are a problem,” Staniscia said. “When we were writing the Florida law, we worried about that, but there was little we could do in the actual law.” Florida’s Department of Business and Professional Regulation licenses agents to work with athletes, he said, but getting licensed is easy. “All you have to do is basically get fingerprinted. They make sure you’re not a felon, and you’re good to go. You don’t need any actual skills or knowledge required by an agent.

“In pro sports there’s a lengthy process to accredit agents,” he added. “I see people blaming the state of Florida” for the bad actors. “But agents were never contemplated by the NCAA, let alone the Florida State High School Athletic Association.”

In the pros, players unions set up the rules for licensing agents. As of now, there is no widespread collective bargaining in college or high school. In the spring of 2024, the National Labor Relations Board ruled that Dartmouth men’s basketball players were employees of the college under federal law and could form a union. The team voted to do so, but the college, insisting that the players are student athletes, not employees, refused to bargain. In January, the team ended its effort, perhaps anticipating that a negative precedent could be set by a soon-to-be Republican-controlled NLRB, the AP reported.

If college unions do catch on in the future and the unions write the rules for licensing agents, their efforts would provide a model for rule-making at the high school level.

“I deal with this on a regular basis,” said Darren Heitner, an attorney who has helped negotiate several major NIL contracts. “Where either someone who is newly licensed or not licensed at all has decided to make a career out of representing these athletes, . . . they’re not necessarily acting in the best interest of the athlete.”

Some representatives, for example, have asked for a fee from a deal, sometimes up to 15 percent, without the athlete understanding the financial relationship beforehand. In other instances, athletes have signed contracts with agents or companies that ask for a commitment beyond the player’s college career. Former University of Florida defensive lineman Gervon Dexter sued the company Big League Advance in 2023 after agreeing the previous year to accept a one-time payment of $436,485 in exchange for 15 percent of all his future pro earnings. Dexter is currently playing for the Chicago Bears in the NFL. According to Florida law, the contract could be considered a “predatory loan,” since the state’s NIL guidelines specifically limit deals to the duration of an athlete’s college career. Contracts that bind high school athletes to long-term relationships could be especially damaging.

Heitner said parents should do their homework before reaching any kind of deal. “Sometimes you have parents who are very much involved, in the right ways,” he said, “and checking all the service providers to ensure everyone who’s acting in a fiduciary capacity has the best interest of their children in mind. . . . Other times, they have their hands out.”

EdNext in your inbox

Sign up for the EdNext Weekly newsletter, and stay up to date with the Daily Digest, delivered straight to your inbox.

Money Isn’t Everything

For Jason Seaborn, Alabama’s NIL rules directly affect his family and his son Trent’s football career. Trent was raised in Ewa Beach, Hawaii, and started training as a young child with Galu Tagovailoa, father of NFL quarterback Tua Tagovailoa. When Seaborn wanted to move his family to a more affordable place, the Tagovailoas suggested Alabama, where Tua had become a superstar at the University of Alabama. Trent was an 8th grader when he threw his first touchdown for Thompson High School in Alabaster, Alabama. By the time he was 15, sponsorship opportunities started coming his way.

“A marketing agent had a deal in hand from Leaf Trading Cards for Trent,” Seaborn said. “It was a seven-figure deal over three years. But the only way to do the deal was to move out of Alabama into a state that allows NIL.”

Trent is considered one of the top recruit nationally in the high school class of 2027. But Seaborn said that Trent isn’t unique, that he’s hearing from several parents that companies are making similar offers to their kids. Seaborn believes the companies are trying to sign players early in their careers before they become more expensive.

“Don’t get me wrong,” Seaborn said. “We could use that money. But we’re happy here. When I approached Trent about the deal, he had no interest in leaving his teammates and friends.”

Seaborn leaned on the Tagovailoas for advice during this process. Tua has had his ups and downs in the NFL, but he recently signed a four-year, $212 million contract with the Miami Dolphins.

“The Tagovailoas reminded me that if Trent keeps working, everything will fall into place,” Seaborn said, though he acknowledges that his son may not make it into the NFL. “We want to teach our kids to chase their dreams, not chase money.”

The Future of High School Sports

High school sports stand at an important crossroads. The extent of NIL’s impact is hard to predict. Noll believes it’s only a matter of time until there’s a national high school football league that mirrors college football. Then the players could become national celebrities and sign more-lucrative marketing deals. Even if that scenario doesn’t play out, underestimating the breadth of NIL deals could be a mistake for high school administrators and coaches.

“They’re educators,” Carter said. “Principals, coaches, and athletic directors tend to be more conservative and give answers to why they don’t support NIL that have to do with the legacy,” saying things like, “‘It’s not how I played high school sports. It’s going to disrupt the locker room, chip away at the chain of command.’” But Carter said these educators will soon need to acknowledge that NIL “is the reality of the high school environment of 2024, and it’s not 1996.”

Carter, who advises several states on NIL policy, believes that NIL provides an educational opportunity for students: “That student athlete is going to have to meet with a business, do research, develop a presentation to discuss what they’re going to offer to do in exchange for compensation,” Carter said. They will have to review, understand, and agree to a contract, and then follow through on their obligation to perform services in exchange for compensation. “There’s some learning around professional development, career development, resume writing, money management. But that message hasn’t broken through in high school yet.”

It’s tempting to write off high school NIL because most students are not talented enough to earn any revenue from athletics. But it’s worth protecting the stability of high school sports and the opportunity for athletes of all skill levels to participate. Most kids, Niehoff pointed out, will end up in careers unrelated to professional sports, but “they’re going to do really well because of their experience in athletics and the successes that they had with relationships they’ve formed. It’s important to remember why sports matter. Education-based athletics align with the mission and vision of the school through the traditional academic experience.”

Colleges and high schools share an important reality when it comes to NIL: its unpredictability. The NCAA and major sports conferences are continually rewriting their rules to accommodate new realities. High schools are just beginning to encounter similar challenges and will have to adapt quickly to stay ahead of a rapidly changing marketplace.

“This is going to take a long time to figure out,” Noll said. “We’re at the top of the first inning in the overall battle. Where it goes from here, no one exactly knows.”

Andrew Perloff is a freelance writer and producer and the co-host of the nationally syndicated sports-radio program “The Maggie and Perloff Show.”

The post The Marketing of High School Athletes: A Rolling Tide appeared first on Education Next.