The brain remembers what gave you food poisoning

Grape Kool-Aid helps show how one meal can create lasting food avoidance in mice. The post The brain remembers what gave you food poisoning appeared first on Popular Science.

If you get food poisoning after eating eggs, there’s a good chance that it will take awhile before you can even handle the thought of eating a nice savory omelet again. That food aversion can be really strong. Now, a team of neuroscientists studying mice have found the exact “memory hub” in their brain that is responsible for this reaction. The findings are detailed in a study published April 2 in the journal Nature and could lead to future clinical treatments.

‘One-shot learning’ vs. the ‘meal-to-maliase’ delay

Instead of learning through repeated trial and error or experiences, one-shot learning is when a single experience creates a lasting memory in the brain. It is most commonly associated with traumatic events that lead to anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and psychosis.

Something similar can happen with a food poisoning experience and it is all too common. The CDC estimates that food poisoning sickens 48 million people in the United States every year.

“I haven’t had food poisoning in a while, but now whenever I talk to people at meetings, I hear all about their food poisoning experiences,” Christopher Zimmerman, a study co-author and lead postdoctoral fellow at the Princeton Neuroscience Institute (PNI) at Princeton University, said in a statement.

While this kind of one-shot learning is common with food poisoning–and makes logical sense–the time gap involved has puzzled scientists. Unlike touching something hot and feeling immediate pain, food poisoning involves a significant delay between when the contaminated food is eaten and getting sick. Zimmerman calls this the “meal-to-malaise” delay.

Drinking the Kool-Aid

For a closer look at the brain mechanisms behind avoiding certain sickening foods, Zimmerman turned to an item that might be sitting in your kitchen pantry–grape Kool-Aid. The lab mice had never had this specific flavor and were asked to try it.

“It’s a better model for how we actually learn,” Zimmerman said. “Normally, scientists in the field will use sugar alone, but that’s not a normal flavor that you would encounter in a meal. Kool-Aid, while it’s still not typical, is a little bit closer since it has more dimensions to its flavor profile.”

The mice eventually learned that poking their nose in a special area of their cage would deliver a drop of Kool-Aid. Thirty minutes after their first taste, the mice received a one-time injection which caused a temporary food poisoning-like illness.

When the mice were offered a choice two days later, the mice strongly avoided the once-appealing purple drink and preferred plain water.

[ Related: Scientists finally figured out why tomatoes don’t kill you. ]

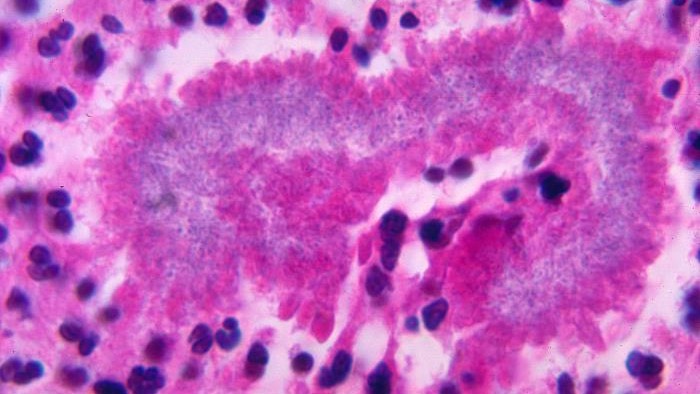

Into the central amygdala

What stuck out to Zimmerman and study co-author and Princeton neuroscientist Ilana Witten is where in the brain this juice/illness association is found: the central amygdala. This small group of cells towards the bottom of the brain is involved in emotion and fear learning. It also processes a great deal of information from our environment, including both smell and taste.

“If you look across the entire brain, at where novel versus familiar flavors are represented, the amygdala turns out to be a really interesting place because it’s preferentially activated by novel flavors at every stage in learning,” Zimmerman said. “It’s active when the mouse is drinking, when the mouse is feeling sick later, and then when the mouse retrieves that negative memory days later.”

According to the team, these results show how critical the central amygdala is at every step along the way of learning.

They then traced how illness signals from the gut reach the brain. Using hints from previous research, they identified specialized hindbrain cells that have a specific protein called Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide (CGRP) and is directly connected to the central amygdala. Stimulating these cells 30 minutes after a mouse’s Kool-Aid experience re-created the same aversion as real food poisoning. Feeling sick also caused the Kool-Aid-activated neurons to reactivate.

“It was as if the mice were thinking back and remembering the prior experience that caused them to later feel sick,” Witten said in a statement. “It was very cool to see this unfolding at the level of individual neurons.”

Leveraging memory recall

The team suspects that new flavors may “tag” certain brain cells to stay sensitive to illness signals for hours after eating. This tag allows those cells to be specifically reactivated by sickness and connect a cause and effect despite the time delay.

According to the team, this type of research opens up new ways of understanding how the brain forms connections between a variety of distant events.

“Often when we learn in the real world, there’s a long delay between whatever choice we’ve made and the outcome. But that’s not typically studied in the lab, so we don’t really understand the neural mechanisms that support this kind of long delay learning,” Zimmerman said. “Our hope is that these findings will provide a framework for thinking about how the brain might leverage memory recall to solve this learning problem in other situations.”

The post The brain remembers what gave you food poisoning appeared first on Popular Science.