Should the ISS be dirtier? Cleanliness could be making astronauts sick.

The space station's microbial environment most closely resembles a hospital isolation room. The post Should the ISS be dirtier? Cleanliness could be making astronauts sick. appeared first on Popular Science.

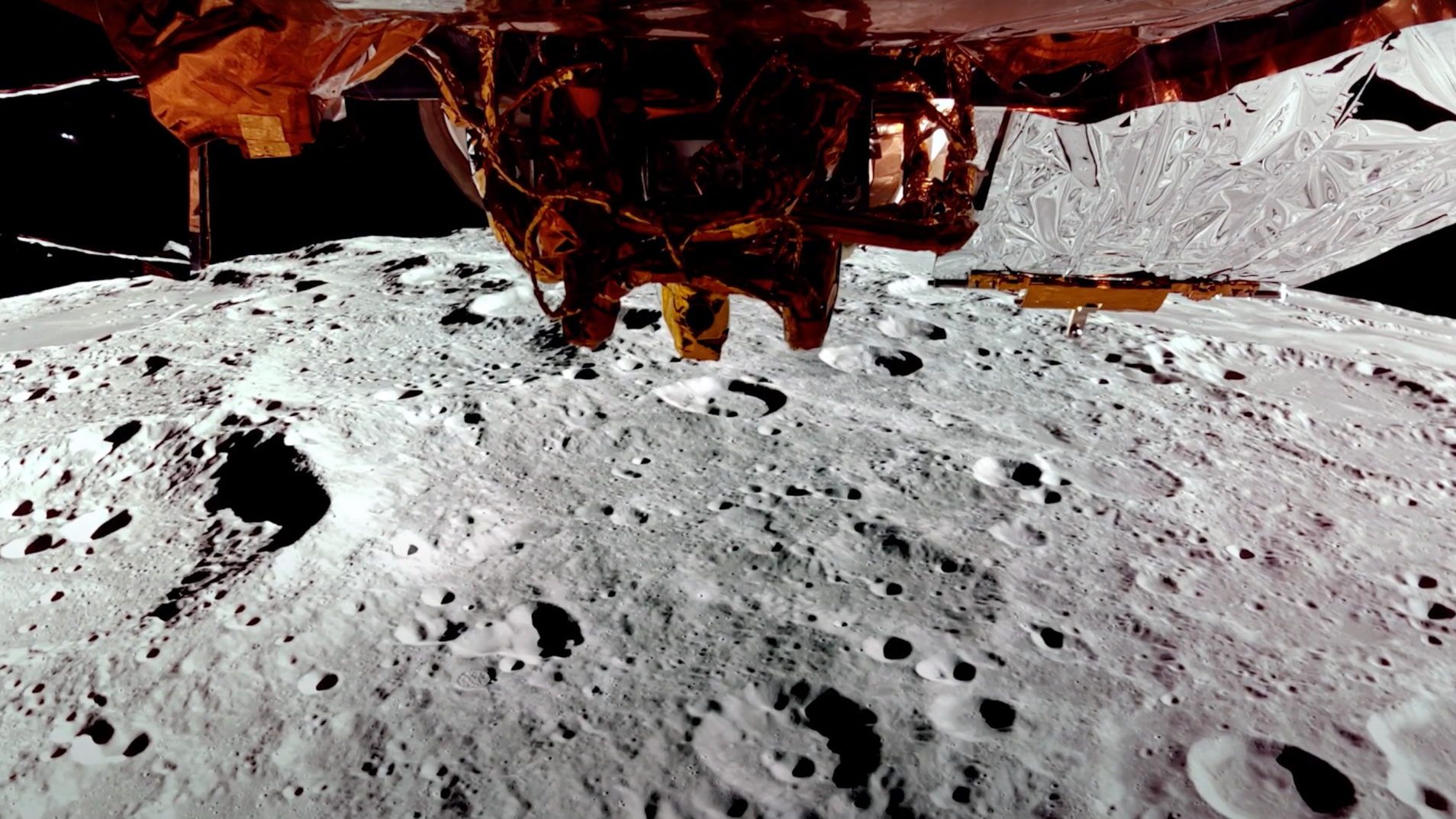

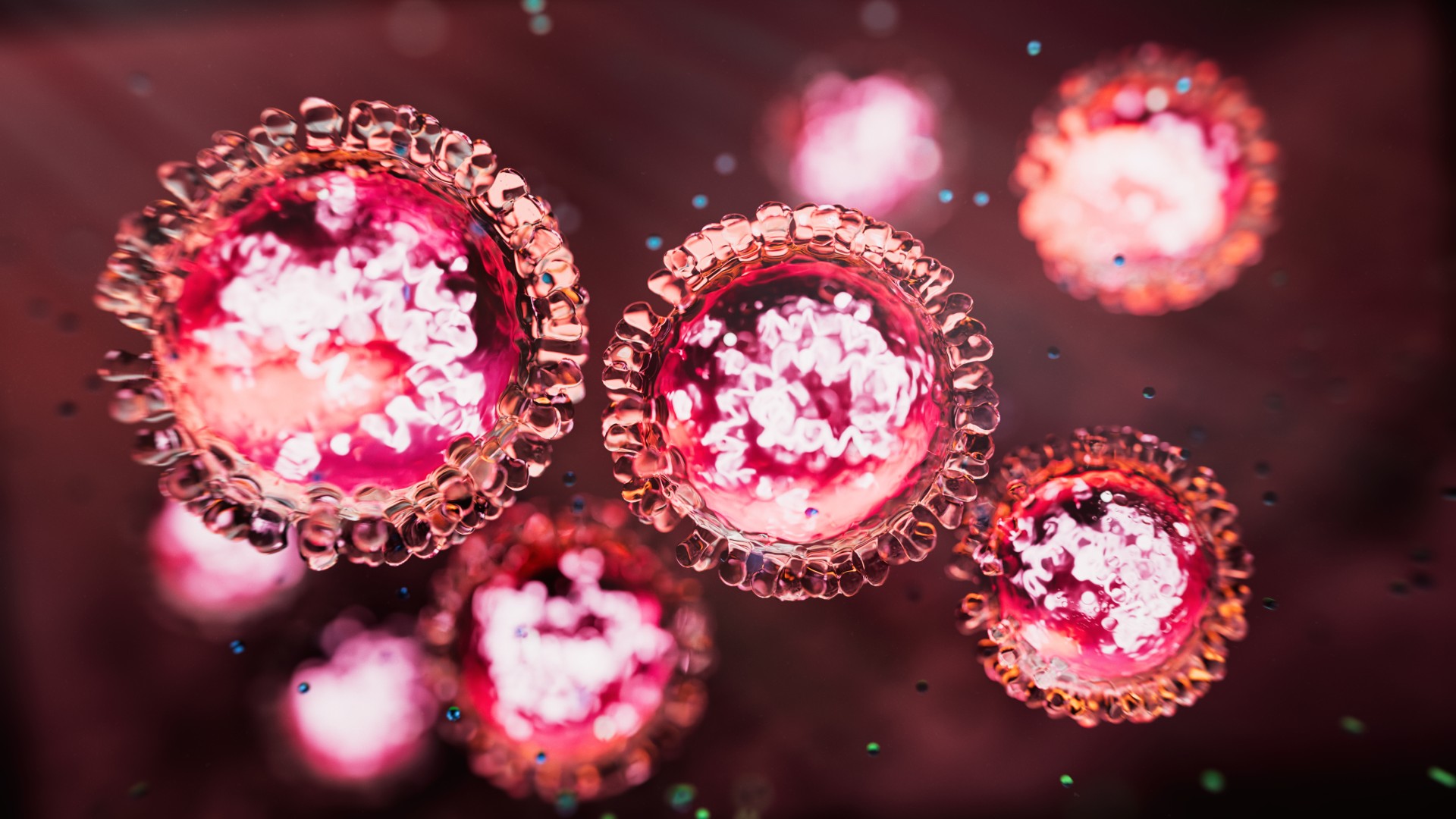

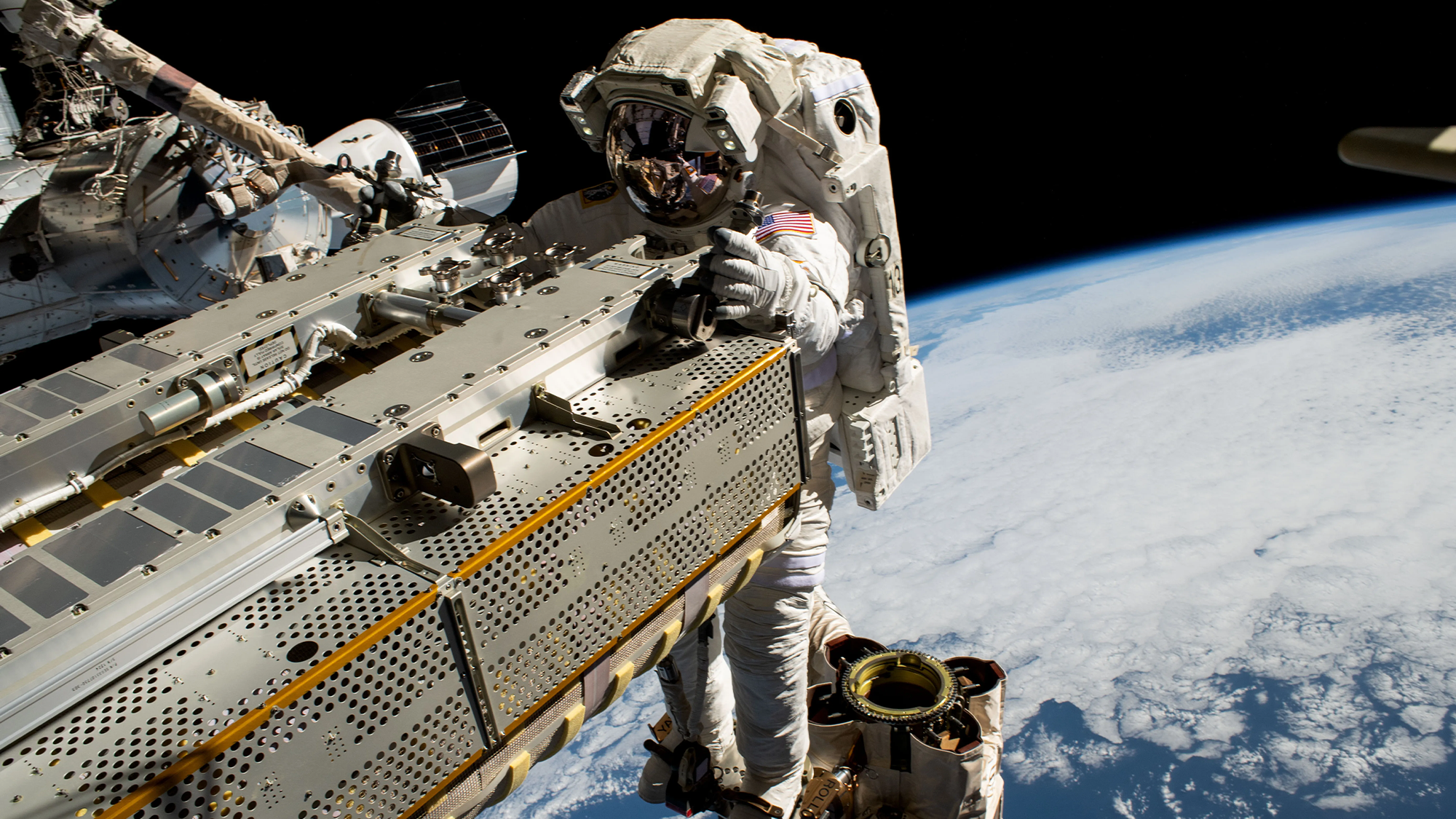

Far away from Earth, there’s an entire intriguing world of microbes to explore. Aboard the International Space Station (ISS), quasi-extraterrestrial life is growing and replicating. Viruses, bacteria, and fungi carried on the bodies of astronauts, building materials, and food all make their way to the ISS despite best efforts to avoid contamination. Once aboard, certain microbes thrive, but a new study suggests it might not be the most ideal mix.

The space station’s microbiome represents an artificial extreme. It lacks diversity and contains a disproportionate amount of antimicrobial resistance genes, according to research published February 27 in the journal Cell. At the same time, the ISS is full of unique and mysterious chemical compounds.

Together, the research team suggests these two factors may be contributing to the ailments and immune dysfunction many astronauts experience on the job. Skin rashes, sudden allergies, hypersensitivity, and re-emerging latent viruses like the kind that cause mononucleosis and herpes are common among space crews. A better understanding of the microbial and chemical conditions of space infrastructure could help engineers and scientists make improvements, and keep space-faring humans healthier in the future.

“What are astronauts exposed to? That was really the question being asked,” Pieter Dorrestein, a co-senior study author, chemist and microbiologist at the University of California San Diego, tells Popular Science. “This is particularly important as we’re starting to think about long-term space travel, or maybe even inhabiting other planets,” he says.

Surface swabs

To explore the question, Dorrestein and his collaborators analyzed 737 surface swabs collected by astronauts from the United States Orbital Segment of the ISS, cataloging the microbes and chemicals collected in each sample. They then compared that dataset with control samples and prior data taken from different environments on Earth.

They noted many interesting finds and patterns, but above all, they found a dearth. There’s what astronauts are exposed to, and then what they aren’t. “One way to describe the ISS environment is an extreme absence of molecules and microbes,” Dorrestein says.

That’s not to say the entire ISS was uniform. The team found that , despite a shared air system and the close quarters, different modules within the space station had notably different microbial and molecular profiles. An area’s function was the biggest determiner of the germ and chemical cocktail lingering on surfaces. For example, the h module used for cooking and dining was host to more food-derived microbes. The module that houses the waste and hygiene compartment contained more germs associated with human feces and chemical signatures of urine.

But overall, the scientists documented low microbial diversity across surfaces in the United States Orbital Segment, compared with samples from Earth. The microbes found aboard the ISS encompassed only about 6 percent of the major clades on the bacterial phylogenetic tree. By comparison, homes on Earth host between 10 and 15 percent of these clades and outdoor environments nearly 30. Positioned along the spectrum of known microbiomes, the space station most closely resembles that of a COVID-19 isolation dorm or a highly sanitized hospital.

[ Related: Six months in space is not that bad for your brain. ]

Forever chemicals in space

As you might expect, the kinds of microbes present in natural settings were largely missing. Instead, most of the bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microorganisms were those associated with the human body. The most prevalent bacterial genus was staphylococcus, which generally lives on human skin and in our mucus membranes.

The notable gaps in the space microbiome could be cause for concern, according to the study. It’s well known that exposure to a wide array of microorganisms plays a role in immune system health. People who grow up in relatively aseptic city apartments are more likely to develop asthma and allergies than those who spend their childhoods on farms, for instance. It’s possible that going without key microbial exposure for months at a time might trigger astronauts’ immune systems to malfunction.

Among the microbes that were found, the scientists identified more than 1,000 genes for antimicrobial resistance (AMR) circulating in more than 90 percent of the samples. “It is a lot. It is an increase over terrestrial environments,” Dorrestein says. AMR genes, alone, aren’t necessarily a problem. However, if they’re acquired by a human pathogen, it could spell serious illness for space travelers.

The space station’s chemical profile proved a little more difficult to pin down. The researchers found hundreds of molecules in their chemical samples, but could only identify a small fraction. For 65 percent, the researchers were unable to even trace likely sources, let alone determine structure. “If we’re going to understand space travel, we need to be able to [better understand] these molecules,” says Dorrestein.

Of the identified compounds, most were from bacterial sources (the products of standard germ metabolism). Others came from food, personal care products, cleaning supplies, or building materials. Notably, the scientists found industrial chemicals like PFAS and phthalates which are known to have negative human health effects. Despite the difficulty in identifying most of the chemicals, what could be distinguished echoed the molecular conditions of a highly urbanized, synthetic environment. “These findings further position the ISS as an extreme, human-input-dominated built environment,” the authors wrote in the study.

While the presence of certain chemicals is cause for concern, Dorrestein notes that the lack of certain other compounds could pose its own risk. Though less studied than microbiomes, molecular diversity may also confer health benefits. For example, certain dietary compounds are known to interact with gut bacteria to offer an immune boost, he explains. More research would be needed to understand how the specific chemical context of the ISS is impacting astronauts.

Rub some dirt in it

However, one chemical finding stands out. In Node 3, the zone astronauts use for exercise and bathroom purposes, the chemical profile included a strong signal of cleaning products and disinfectants. At the same time, this node had the most diverse microbial environment– signaling a potential relationship between constant cleaning and microbe growth. Dorrestein notes the causality is unclear. It could be that there’s more germs, and so the area is cleaned more frequently. Or, it might be that frequent cleaning fosters an environment where no single bug can take over. Though diverse microbiomes are good in many contexts, that might not be the case here, where many of the microbes seem to be evolving and passing around genes for antimicrobial resistance. Frequent disinfection could be upping the likelihood of hard-to-treat pathogens emerging.

Thankfully, the study offers one potential way forward: Add some dirt. “Introducing an environmental non-saline soil matrix could potentially alter the microbial composition of industrialized built environments, including the ISS, to align more closely with the microbial communities found in environmentally exposed habitats,” write the researchers.

[ Related: There’s a lot we don’t know about the International Space Station’s ocean grave.]

That’s a very roundabout, technical way of saying that (thoughtfully) bringing some literal Earth to space might make the conditions healthier for humans, Dorrestein explains.

He doesn’t envision laying down shovel-fulls of compost on the ISS floor, but perhaps sterilized, then carefully re-inoculated soil could be used to grow plants and spread beneficial microbes for the astronauts’ benefit. Fermented foods like natto and kombucha might help too, he suggests. And alternate, less harsh and more probiotic cleaning methods may be another tool.

Yet, to truly determine the best ways to boost space immunity, maximize astronaut health, and enable planetary exploration, more research is needed. The scientists view this work as a starting point. “Our study really creates a resource to continuously learn from. There’s a lot of signals we detect that we don’t yet know how to interpret,” Dorrestein says. “We still have a lot to learn about the microbes and chemicals in space travel.

The post Should the ISS be dirtier? Cleanliness could be making astronauts sick. appeared first on Popular Science.