Operational Considerations for Managing Stateful Workloads

When managing stateful workloads, whether in Kubernetes or traditional infrastructure, operational concerns like isolation, lifecycle management, security, disaster recovery, scalability, and observability take center stage. While the examples focus on AWS, PostgreSQL, and Kubernetes, the principles and best practices discussed here are broadly applicable to any environment. This article approaches these topics from an operations perspective, prioritizing reliability, maintainability, and resilience. The goal is not just to run a database, but to ensure it operates efficiently, scales properly, and remains secure in real-world conditions. We’ll explore key aspects of running stateful workloads, from managing failure domains to ensuring observability, and how these impact both operations teams and developers. Whether you’re running a database in a cloud-native setup or on bare metal, these strategies will help you build a robust, well-managed system. Table of Contents Isolation Lifecycle management Security Disaster Recovery Scalability Prepare for the Ugly Observability Stakeholders Let’s dive in. Isolation Let's primarily focus on the isolation options for a database. 1. Shared Database, Shared Schema All tenants use the same database and the same set of tables. Each entry includes a tenant_id column to segregate data. Efficient use of resources is debatable because of the WHERE tenant_id will add overhead to each query. Pros: Simplifies deployment and maintenance. Cons: Requires strict tenant-aware data access controls. If you implement a ROW-level ACL (implementation follows). Certain performance bottlenecks as the tenant count grows. Extremely bad If there is a DR scenario: All users will be affected as you will need to rollback ALL the database to the last known good state. botched operations will be global. global recovery increases MTTR. Notes: One can use Row-Level Security (RLS) in Postgres to have some weak aggregated form of isolation, but it's not isolation. We will dive into this subject as part of security. Using table prefixes for sharding tenants is a bad idea. DONT. 2. Shared Database, Separate Schema Each tenant has its own schema within a shared database. Table names etc within the schema should be consistent to simplify development. Schema-based isolation improves security and performance. From a security perspective, this isolation is considered weak because you need to protect yourself from: Schema Privilege Escalation Cross-Schema Injection Risks Pros: Better sharding of data while sharing infrastructure. Queries no longer include the WHERE tenant_id portion which adds overhead to queries. Allows per-tenant schema customizations. Avoid if possible. Future proof to move to more isolated setups. Cons: More complex migrations and schema updates. If not properly managed, restoring one schema could expose data from others due to shared connections. Increased administrative overhead, but solvable. Still need to have strict database logs and alerts to detect unauthorized access because all users will be working on the same process. Complicated backups because each schema should have a dedicated backup process. Can't use volume snapshots for backups. They will rever the global state meaning you affect all tenants. 3. Separate Databases per Tenant, Shared database instance Each tenant has its dedicated database but all tenants use the same CPUs. Ensures complete data isolation. Pros: All benefits for Shared Database, Separate Schema setup plus: Strong ACL offers improved security. Eases tenant-specific backups and compliance handling. Simplest and fastest DR. DR is not global. Cons: Migration and schema updates are still complex. Higher infrastructure and management overhead. Will discuss the solution later in this doc. Efficient scaling needs more thought. 4. Separate databases instance per tenant Each tenant is running on their own database, probably in their dedicated namespace, or perhaps in a different region, etc. At this level of isolation, it doesn't matter. Even stronger isolation because you don't rely only on db-level ACL but also network policies/firewall rules. In essence it's a special case of the 3rd option with: Pros: Even stronger isolation Cons: Capacity planning and optimization overhead will be significant. To benefit from this level you need to ensure that the undelaying infrastructure setup is extremely secure so your processes are not exposed to other people running on the same cloud infra eg NodeLaunchTemplate: Type: AWS::EC2::LaunchTemplate Properties: LaunchTemplateData: MetadataOptions: HttpPutResponseHopLimit: 1 HttpTokens: required EksCluster: Type: AWS::EKS::Cluster Properties: Name: !Sub "${AWS::StackName}" RoleArn: !GetAtt ClusterIamRole

When managing stateful workloads, whether in Kubernetes or traditional infrastructure, operational concerns like isolation, lifecycle management, security, disaster recovery, scalability, and observability take center stage. While the examples focus on AWS, PostgreSQL, and Kubernetes, the principles and best practices discussed here are broadly applicable to any environment. This article approaches these topics from an operations perspective, prioritizing reliability, maintainability, and resilience. The goal is not just to run a database, but to ensure it operates efficiently, scales properly, and remains secure in real-world conditions. We’ll explore key aspects of running stateful workloads, from managing failure domains to ensuring observability, and how these impact both operations teams and developers. Whether you’re running a database in a cloud-native setup or on bare metal, these strategies will help you build a robust, well-managed system.

Table of Contents

- Isolation

- Lifecycle management

- Security

- Disaster Recovery

- Scalability

- Prepare for the Ugly

- Observability

- Stakeholders

Let’s dive in.

Isolation

Let's primarily focus on the isolation options for a database.

1. Shared Database, Shared Schema

- All tenants use the same database and the same set of tables.

- Each entry includes a

tenant_idcolumn to segregate data. - Efficient use of resources is debatable because of the

WHERE tenant_idwill add overhead to each query. -

Pros:

- Simplifies deployment and maintenance.

-

Cons:

- Requires strict tenant-aware data access controls. If you implement a ROW-level ACL (implementation follows).

- Certain performance bottlenecks as the tenant count grows.

- Extremely bad If there is a DR scenario:

- All users will be affected as you will need to rollback ALL the database to the last known good state.

- botched operations will be global.

- global recovery increases MTTR.

Notes:

One can use Row-Level Security (RLS) in Postgres to have some weak aggregated form of isolation, but it's not isolation. We will dive into this subject as part of security.

Using table prefixes for sharding tenants is a bad idea. DONT.

2. Shared Database, Separate Schema

- Each tenant has its own schema within a shared database. Table names etc within the schema should be consistent to simplify development.

- Schema-based isolation improves security and performance. From a security perspective, this isolation is considered weak because you need to protect yourself from:

- Schema Privilege Escalation

- Cross-Schema Injection Risks

-

Pros:

- Better sharding of data while sharing infrastructure.

- Queries no longer include the

WHERE tenant_idportion which adds overhead to queries. - Allows per-tenant schema customizations. Avoid if possible.

- Future proof to move to more isolated setups.

-

Cons:

- More complex migrations and schema updates.

- If not properly managed, restoring one schema could expose data from others due to shared connections.

- Increased administrative overhead, but solvable.

- Still need to have strict database logs and alerts to detect unauthorized access because all users will be working on the same process.

- Complicated backups because each schema should have a dedicated backup process.

- Can't use volume snapshots for backups. They will rever the global state meaning you affect all tenants.

3. Separate Databases per Tenant, Shared database instance

- Each tenant has its dedicated database but all tenants use the same CPUs.

- Ensures complete data isolation.

-

Pros:

- All benefits for Shared Database, Separate Schema setup plus:

- Strong ACL offers improved security.

- Eases tenant-specific backups and compliance handling.

- Simplest and fastest DR.

- DR is not global.

-

Cons:

- Migration and schema updates are still complex.

- Higher infrastructure and management overhead. Will discuss the solution later in this doc.

- Efficient scaling needs more thought.

4. Separate databases instance per tenant

- Each tenant is running on their own database, probably in their dedicated namespace, or perhaps in a different region, etc. At this level of isolation, it doesn't matter.

- Even stronger isolation because you don't rely only on db-level ACL but also network policies/firewall rules.

- In essence it's a special case of the 3rd option with:

-

Pros:

- Even stronger isolation

-

Cons:

- Capacity planning and optimization overhead will be significant.

- To benefit from this level you need to ensure that the undelaying infrastructure setup is extremely secure so your processes are not exposed to other people running on the same cloud infra eg

NodeLaunchTemplate: Type: AWS::EC2::LaunchTemplate Properties: LaunchTemplateData: MetadataOptions: HttpPutResponseHopLimit: 1 HttpTokens: required EksCluster: Type: AWS::EKS::Cluster Properties: Name: !Sub "${AWS::StackName}" RoleArn: !GetAtt ClusterIamRole.Arn EncryptionConfig: - Provider: KeyArn: !GetAtt ClusterSecretsKMSKey.Arn Resources: - secrets Logging: ClusterLogging: EnabledTypes: - Type: api - Type: audit - Type: authenticator - Type: controllerManager - Type: scheduler ResourcesVpcConfig: EndpointPublicAccess: false EndpointPrivateAccess: true KubeAPIServer: HTTPTokens: required HTTPPutResponseHopLimit: 1

In a Kubernetes context you should be using different and unique security contexts per instance, dropped capabilities, and with AppArmor or SELinux, eg:

---

securityContext:

runAsUser:1000

runAsGroup:3000

fsGroup:2000

readOnlyRootFilesystem: true

allowPrivilegeEscalation: false

---

securityContext:

runAsUser:1001

runAsGroup:3001

fsGroup:2001

readOnlyRootFilesystem: true

allowPrivilegeEscalation: false

Lifecycle management

Use two different jobs to handle the distinct aspects of the application lifecycle. The first Job runs only on installation; its single responsibility is to create the database with the required parameters. It will run even before installation as we use the pre-install hook, which means before any application-specific resources are created.

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{ include "chart.fullname" . }}-db-create-{{ randAlphaNum 5 | lower }}

annotations:

"helm.sh/hook": pre-install

"helm.sh/hook-weight": "-20"

"helm.sh/hook-delete-policy": before-hook-creation

"argocd.argoproj.io/hook": "PreSync"

"argocd.argoproj.io/hook-delete-policy": "BeforeHookCreation"

"argocd.argoproj.io/job-cleanup": "keep"

spec:

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: db-create

and also define the migrate job that will run after the db-create and will setup the required schema for the application to function.

apiVersion: batch/v1

kind: Job

metadata:

name: {{ include "chart.fullname" . }}-db-migrate-{{ randAlphaNum 5 | lower }}

annotations:

"helm.sh/hook": pre-install,pre-upgrade

"helm.sh/hook-weight": "-10"

"helm.sh/hook-delete-policy": before-hook-creation

"argocd.argoproj.io/hook": "Sync"

"argocd.argoproj.io/hook-delete-policy": "BeforeHookCreation"

"argocd.argoproj.io/job-cleanup": "keep"

spec:

template:

spec:

restartPolicy: Never

containers:

- name: db-migrate

the sequence of events should look something like this:

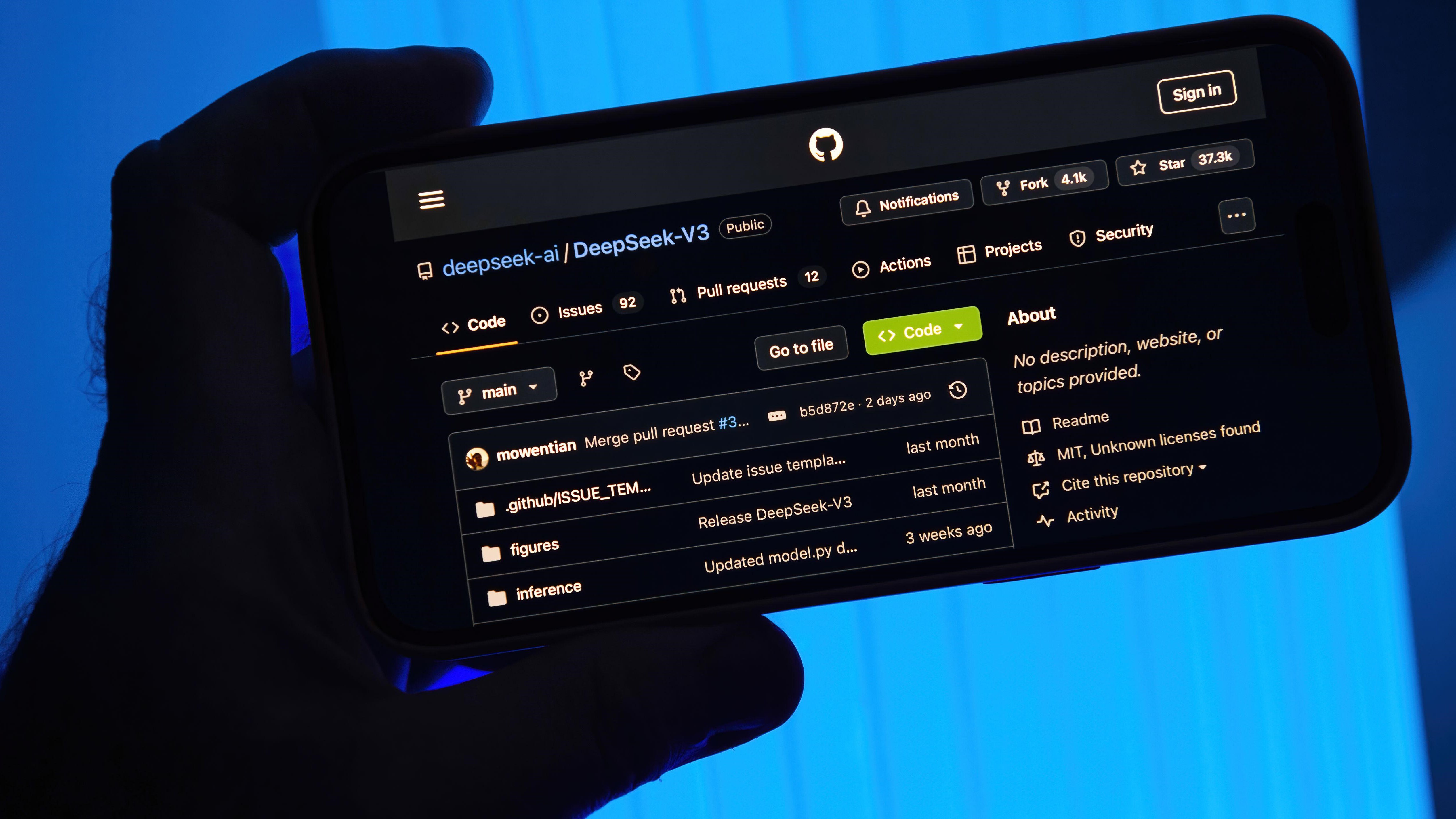

For a deeper dive into the inner workings of databases, I highly recommend: Fundamentals of Database Engineering paired with Database Internals.

Security

Security includes multiple aspects that we will approach.

Access

In a nutshell, access is who can knock on your door, meaning who can reach the port the database listens to. This might be enforced by security groups or network policies etc but in essence, we are talking about firewalls here. Following is an example of a NetworkPolicy (Kubernetes firewall) that allows an app, the vault, and Prometheus to access it. Here we allow Prometheus to run on the monitoring namespace, the replicas from the same namespace, and the vault from the vault namespace.

apiVersion: networking.k8s.io/v1

kind: NetworkPolicy

metadata:

name: app-db-postgresql-primary-ingress

labels:

app.kubernetes.io/instance: app-db

app.kubernetes.io/component: primary

spec:

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/instance: app-db

app.kubernetes.io/name: postgresql

app.kubernetes.io/component: primary

ingress:

- from:

- podSelector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/instance: app-db

app.kubernetes.io/name: postgresql

app.kubernetes.io/component: read

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: vault

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/instance: vault

app.kubernetes.io/name: vault

ports:

- port: 5432

- from:

- namespaceSelector:

matchLabels:

kubernetes.io/metadata.name: monitoring

podSelector:

matchLabels:

app.kubernetes.io/name: prometheus

ports:

- port: 9187

Keep in mind that you will probably need to give Grafana or Metabase etc access to your database. A good approach is to do this using the replicas to ensure that a big query doesn't take down prod.

Authentication

Authentication is what happens after someone knocks on your door (port). What is required is for them to prove that they are who they claim to be in an acceptable format. There are two main types of methods to do this but always remember that no matter which approach you select what you want is to have a safe central place where these are controlled. If you choose to do a bit of mix a match, make sure that you have a clear separation of methods with a clear understanding of why. The worst thing you can do here is to leverage multiple ways to authenticate on the same resources because you will lose track. Also to avoid surprises make sure that your authentication methods will work for production requirements and developers.

Personally, I recommend using service authentication between "stuff" that is offered by your cloud provider and your cluster's workloads and credentials between your engineering teams, your applications, and the databases.

Authentication through roles

Authentication through roles means that you either trust some services metadata or their serviceAccount to allow them to do a particular action.

Authentication through credential

Authentication through credentials means that the service or user can produce a username/password combination that allows you to connect. A bit of a heads-up here is that it's safer to use files as a source of credentials for any application instead of using environmental variables for the simple reason that if someone runs ps env they will read the entire environment of the container and thus the credentials used. Also, consider that dynamic credentials are far better than static ones. Using dynamic credentials means that there are no credentials to be saved in the code or reused through .env that might be shared between team members.

Do not try and bend the spoon, that's impossible. Instead, try to realize the truth, there is no spoon.

Now let's get dirty, in reality, your application should have two processes, one that handles the schema through migrations and a second for normal operation. This means that you will have some secrets in the cluster that will look like this:

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: {{ include "chart.fullname" . }}-db-migrate-credentials

type: Opaque

stringData:

DB_USER:

DB_PASSWORD:

DB_NAME:

---

apiVersion: v1

kind: Secret

metadata:

name: {{ include "chart.fullname" . }}-db-runtime-credentials

type: Opaque

stringData:

DB_USER:

DB_PASSWORD:

DB_NAME:

There are several approaches to facilitating this but here I will dive into my favourite.

Hashicorp vault

I consider Vault the root user of all databases. It gives access to all of them and with secret engines, eg postgres it can generate ephimeral credentials.

These credentials can be mapped to IAM roles, or use external secrets operator or vault secrets operator. Whichever approach is in the end, a short-lived username/password is generated that accesses the single database or schema with the required permissions. Keep in mind that these should be different for the process that handles schema (which needs to have elevated access eg to create a table) and for the normal app/role that will be allowed to only read/write/update but never delete or drop. The beauty of this is that from the developer's perspective, it's the same secret (though different values) that the application uses. So they will not need to bother with the overhead of this logic in the application code. The downside of this approach is that when values change, it will require that the pod gets restated which may cascade and have issues with PDB.

An example generate the aforementioned secrets using the vault and external secrets operator is:

vault write database/config/my-postgresql-database \

plugin_name=postgresql-database-plugin \

connection_url="postgresql://{{username}}:{{password}}@your-db-host:5432/postgres?sslmode=disable" \

allowed_roles="db-admin, runtime-user" \

username="vaultuser" \

password="vaultpassword"

vault write database/roles/db-admin \

db_name=my-postgresql-database \

creation_statements="CREATE ROLE \"{{name}}\" WITH LOGIN PASSWORD '{{password}}'; GRANT ALL PRIVILEGES ON DATABASE mydb TO \"{{name}}\";" \

revocation_statements="REVOKE ALL PRIVILEGES ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA public FROM \"{{name}}\"; DROP ROLE \"{{name}}\";" \

default_ttl="5m" \

max_ttl="1h"

vault write database/roles/runtime-user \

db_name=my-postgresql-database \

creation_statements="CREATE ROLE \"{{name}}\" WITH LOGIN PASSWORD '{{password}}'; GRANT CONNECT ON DATABASE mydb TO \"{{name}}\"; GRANT USAGE ON SCHEMA public TO \"{{name}}\"; GRANT SELECT ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA public TO \"{{name}}\";" \

revocation_statements="REVOKE ALL PRIVILEGES ON ALL TABLES IN SCHEMA public FROM \"{{name}}\"; DROP OWNED BY \"{{name}}\"; DROP ROLE \"{{name}}\";"

default_ttl="30m" \

max_ttl="1h"

Then by using some facilitator service, you can have dynamic secrets where they need to be. The ones most often used are either the vault agent which will use some annotations to setup the credentials for the pod or the external secrets operator which will interact with the vault and generate the Kubernetes secret that will be used. Some more examples

---

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1alpha1

kind: VaultProvider

metadata:

name: vault-provider

spec:

vault:

address: "https://your-vault-address:8200"

auth:

tokenSecretRef:

name: vault-token

key: token

---

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1alpha1

kind: ExternalSecret

metadata:

name: db-admin-credentials

spec:

provider:

vault:

path: "database/creds/db-admin" # Use the appropriate role for DB Admin or Runtime User

server: "https://your-vault-address:8200"

auth:

tokenSecretRef:

name: vault-token

key: token

secretStoreRef:

name: vault-provider

target:

name: db-credentials

creationPolicy: Owner

data:

- secretKey: DB_USER

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/db-admin

property: data.username

- secretKey: DB_PASSWORD

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/db-admin

property: data.password

- secretKey: DB_NAME

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/db-admin

property: data.dbname

---

apiVersion: external-secrets.io/v1alpha1

kind: ExternalSecret

metadata:

name: db-runtime-credentials

spec:

provider:

vault:

path: "database/creds/db-runtime" # Use the appropriate role for DB Admin or Runtime User

server: "https://your-vault-address:8200"

auth:

tokenSecretRef:

name: vault-token

key: token

secretStoreRef:

name: vault-provider

target:

name: db-credentials

creationPolicy: Owner

data:

- secretKey: DB_USER

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/runtime-user

property: data.username

- secretKey: DB_PASSWORD

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/runtime-user

property: data.password

- secretKey: DB_NAME

remoteRef:

key: database/creds/runtime-user

property: data.dbname

The main problem is that by the nature of vault etc, not all of these can be automated. It can be scripted but a person who actually has access to the vault will need to be involved to run the required configurations. Unless you create a custom operator that has admin vault access and performs the required actions to setup the particular engine and paths etc. A better approach is to use the Vault agent to automate secret management.

...

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: sb-k8s-template

annotations:

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-inject: "true"

vault.hashicorp.com/role: "myapp-k8s-role"

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-inject-secret-myapp-db: "myapp-db/creds/myapp-db-role"

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-inject-file-secret-myapp-db: "myapp-db.creds"

vault.hashicorp.com/auth-path: "auth/kubernetes"

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-run-as-user: "1881"

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-pre-populate: "true"

vault.hashicorp.com/agent-pre-populate-only: "false"...

Whichever method you select, keep in mind that at the end it will mean that the client gets a token/key to use. Basically, a passport that they will then use for authorization.

Authorization

Authorization is what happens after a user or a process uses their credentials or token and has some form of access. So after a connection has been established and authentication is complete, authorization answers the question: what can I do?

Shared Database, Shared Schema

Previously we have mentioned Row-Level Security (RLS). RLS is a method to define in a shared database and shared tables, who can do what. In essence, what you want is to try and block tenant1 from reading or writing entries that belong to tenant2. RLS is a way to achieve this result but at a computational cost for the database. For each query the database will need to check if the cursor has the required access to the particular row and then perform the actual query with the mentioned WHERE tenant_id. All this will add delay.

--- Enable Row-Level Security (RLS) on the target table.

ALTER TABLE orders ENABLE ROW LEVEL SECURITY;

--- Create a Security Policy for Tenants (restrict access to own rows).

CREATE POLICY tenant_row_access

ON orders

FOR ALL

USING (tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant')::UUID);

--- Ensure INSERT operations only allow the correct tenant_id.

CREATE POLICY tenant_insert_policy

ON orders

FOR INSERT

WITH CHECK (tenant_id = current_setting('app.current_tenant')::UUID);

--- Grant basic permissions on the orders table to tenant-specific roles.

GRANT SELECT, INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE ON orders TO tenant_role;

--- Set the tenant ID in the session (should be done by the application per request).

SELECT set_config('app.current_tenant', 'tenant-123', false);

--- Example: Tenant 123 querying the orders table (will only return their own rows).

SELECT * FROM orders;

--- Example: Trying to insert an order for another tenant (should fail).

INSERT INTO orders (id, tenant_id, order_name) VALUES (1, 'tenant-999', 'Test Order');

Nevertheless, even with RLS the two issues remain:

- It's considered easy to jailbreak.

- You will still need to create a migrations-like process that will generate and update the RLS as you add new tenants.

I would suggest experimenting with using EXPLAIN and EXPLAIN ANALYZE on your data to see how it works on your system. Depending on the scale, some organizations will be happy to accept the RLS overhead, and for some, it will be a significant price that will drive them to adopt a different approach. From experience what tends to happen is that organizations start by using RLS and at some point start to split their clients into higher tiers where multitenancy is offered.

Shared Database, Separate Schema or better

Once you have stopped using Shared Database with Shared Schema the authorization portion becomes rather simple and fast. This is because you now have access rules that are applied once when you start the cursor to the database and it will no longer need to be re-calculated for each query the cursor makes.

Disaster Recovery

Disaster Recovery (DR) is a set of policies, tools, and procedures designed to restore IT infrastructure and operations after a disaster (e.g., cyberattacks, hardware failures, natural disasters, or human errors). It ensures business continuity by minimizing downtime and data loss.

Key Components of Disaster Recovery

- Backup & Restore – Regular data backups to on-site, off-site, or cloud storage.

- Disaster Recovery Plan (DRP) – A documented strategy outlining recovery steps, responsibilities, and timelines.

- Recovery Time Objective (RTO) – Maximum acceptable downtime before services must be restored.

- Recovery Point Objective (RPO) – Maximum acceptable data loss measured in time (e.g., last backup timestamp).

In my opinion, a common misconception is that HA setups offer DR. While they can be handy in some cases for example by mitigating restarts, etc through failovers and redundancy, replicas should not be considered disaster recovery sources for the simple reason that they might be also corrupted or lost. Disaster recovery should mean that you have a path from being completely owned. In a nutshell, HA prevents downtime; DR recovers from disaster.

In practice your first concern is backup. Either you use a cronjob to perform a series of dumps or volume snapshots by the database or through Velero, you will be doing something similar to

annotations:

backup.velero.io/backup-volumes: backup

post.hook.restore.velero.io/command: '["/bin/bash", "-c", "[ -f \"/scratch/backup.sql\" ] && PGPASSWORD=$POSTGRES_PASSWORD psql -U $POSTGRES_USER -h 127.0.0.1 -d $POSTGRES_DATABASE -f /scratch/backup.sql && rm -f /scratch/backup.sql;"]'

pre.hook.backup.velero.io/command: '["/bin/bash", "-c", "PGPASSWORD=$POSTGRES_PASSWORD pg_dump -U $POSTGRES_USER -d $POSTGRES_DATABASE -h 127.0.0.1 > /scratch/backup.sql && mkdir -p /bitnami/postgresql/backups && mv /scratch/backup.sql /bitnami/postgresql/backups"]'

pre.hook.backup.velero.io/timeout: 15m

You can define these as complex as required using the RTO and RPO as definite guides. What you really need to pay special attention to is WHERE these are saved and WHY it's safe. To be honest, here the only real solution for this is to use some form of vault lock with WORM capability. For example, Amazon S3 supports WORM (Write Once Read Many) functionality through S3 Object Lock, which allows you to store objects in a way that they cannot be changed or deleted after they have been written. This feature is useful for regulatory compliance and data protection. In practice, this means that even if the ROOT account of the cloud provider gets compromised the backups will be safe. You will need to also configure lifecycle policies to ensure that costs don't skyrocket. Even if you are running on-prem consider using something like AWS PrivateLink to link your local network and store your backups on the cloud.

Again keep in mind that here isolation is your best friend. If you restore a database you restore a database. This means that ALL your clients will be affected. Thus it's very important to use divide and conquer here, meaning create backup and recovery plans that will allow you to perform a partial recovery for only the affected clients. This might mean that you dump all the database in the vault but allow your ops team to set up a partial restore process for the particular clients. Just have these defined and run recovery drills to verify you meet your RTO and RPO.

For a bit more clarity regarding DRPs. A plan is always a good thing and keeping it documented is even better. Documenting a DRP means that you don't just add words in a doc file. I mean that you define strategies and tactics. I mean that you define decision points and have ready recovery scripts. You might do these in bash you might do these in ansible, it doesn't matter. What matters is that you:

* Know if you need to start a recovery.

* Know what is still OK and what you need to recover or otherwise what's the blast radius.

* Know what point in time you need to recover from.

* Know that you have tested these in the past so you don't end up in a deeper hole.

Some solutions worth exploring for DR are:

Scalability

This entire setup considers a single database that can be used for read and write. You can also create different instances and "schedule" your tenants to them to have even balances. But sooner or later you will probably need to leverage different paths for read and write. This means replication, and replication means eventual consistency. Ignoring for now the eventual consistency logic, the architecture for this is as follows:

- Create a high-availability setup. You can use leader election or other strategies, but for simplicity let's assume that the PRIMARY is defined. The optimal approach here is to create read REPLICAS ensuring with anti-affinity that each read replica lives in a different AZ. This is especially important considering that block storage volumes are AZ-locked and can't easily migrate between zones.

- Then you have the issue of query routing. Here again, two main approaches work well, depending if you prefer to pay the development overhead or leverage a standard solution:

- Use a read and a write connection string, and have the application create different connections that produce a read and a read_write cursor to the database. Then the application explicitly selects what to use for each case.

- Use a service like pgPool that will act like a reverse proxy to the database and depending on the query type (selection or update) will route the query to the correct instance type. For a deeper dive visit Load Balancing/Query Routing using PGPOOL-II

Personally, I like the latter approach as it gives this power to the infrastructure teams which are more aware of what runs where etc. You might want to further optimize connectivity by using a way to enable service topology-aware routing between apps and pgPool but also between pgPool and database instance (Exploring the effect of Topology Aware Hints on network traffic in Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service), eg:

apiVersion: v1

kind: Service

metadata:

name: pgpool

annotations:

service.kubernetes.io/topology-aware-hints: "auto"

spec:

topologyKeys:

- "topology.kubernetes.io/zone"

Database High Availability (HA) and Split Brain Risk

In a database high availability (HA) setup that relies on long-running connections, upgrading and migrating to new nodes can introduce the risk of a split-brain scenario. This occurs when multiple nodes operate independently, believing they are the primary, leading to data inconsistency and potential loss of transactions.

Scenario Description

During an upgrade, the following events may unfold:

- A primary database node is migrated or replaced.

- Long-running connections on existing nodes persist, unaware of the topology change.

- A new node is introduced as the new primary, but stale connections may still interact with the old node.

- Both old and new nodes process write operations independently.

- Data divergence occurs due to concurrent writes on both nodes.

Potential Causes of Split Brain

- Long-lived client connections: Clients may not detect topology changes and continue writing to an old node.

- Network partitioning or delays: Temporary network issues can cause nodes to operate independently.

- Failure in leader election mechanisms: If multiple nodes incorrectly assume leadership, they can both accept writes.

- Lack of connection draining: If client connections are not explicitly closed before failover, they may write to an outdated node.

Mitigation Strategies

- Connection Draining: Ensure all active connections are gracefully closed before promoting a new node.

- Automated Failover Testing: Simulate failover scenarios before deploying upgrades.

- Strict Fencing Mechanisms: Implement strict write fencing to prevent stale nodes from accepting writes.

- Short-lived Connections: Design clients to use short-lived or automatically re-established connections after failovers.

Below is a sequence diagram illustrating a split-brain scenario during an upgrade and how it will get resolved either by replicas understanding that they are in split-brain and re-establishing connectivity or through a controller that takes over and handles the recovery.

If this setup seems complex, that's because it is. Especially if you consider that you might have multiple replicas which might also need to get scheduled on new nodes etc. In many ways, it resembles the Tower of Hanoi puzzle—careful sequencing is key. That's why it's better to leverage some tools to help you out. Especially with Postgres, there is an operator that will act as Controller (cloudnativePG) that will offer a great deal of help running operations. In the past, I got some very good results from Patroni. Also,o this is why you need either short-lived connections from your applications or some code to handle these potential errors. If this sounds like a high-risk scenario (and it probably is for most organizations) I would suggest starting with what you are already using, a managed database, and treating it as your primary. Then build a replication system in your cluster. But always keep in mind that you are no longer in ACID land, you are now in eventual consistency land. What has happened is that you traded downtime for ACID and managed to maintain eventual consistency. Make sure that your engineering recognizes this as an architectural reality and business realizes that "One Does Not Simply Walk Into Mordor".

Recommendation: Even If you don't manage to get the buy-in to change the entire architecture of your application, start by creating a single replica for departments that don't need real-time data, like CS, etc. Use the replicas to get some hands-on experience with business intelligence pipelines feeling happy that a huge query will not nuke your database and affect your customers.

The book Designing Data-Intensive Applications is an amazing source to understand how to handle state.

Short or long-lived connections

This is one of the core architectural dilemmas in system design. On one hand, short-lived connections allow you to fail fast and increase the probability of retrieving the most relevant data. However, they come with the overhead of frequently establishing new connections. This cost can be substantial, especially when using SSL/TLS, as it requires an expensive asymmetric encryption handshake to generate a session’s symmetric key. This key might then be used for several minutes—or even just a single query—before the connection is closed. On the other hand, long-lived connections avoid this repeated overhead but introduce complexities, such as handling reconnections, detecting stale or split-brain database replicas, and managing connection pooling effectively.

The right choice depends on your specific use case. However, at a minimum, you should accept the SSL/TLS overhead for the most critical database connections—especially those handling schema changes. These operations are relatively rare but use high-privilege credentials, making security a top priority. Additionally, since database replication typically relies on long-lived connections, ensure these connections are also secured with SSL/TLS. For your application layer, the decision depends on your exact workload and data requirements. Still, I recommend using SSL/TLS for database cursors handling write operations. It’s fascinating how seemingly “small” non-functional requirements can shape fundamental architectural decisions.

Prepare for the Ugly: Ensuring Database Stability in Kubernetes

Running databases in any infrastructure involves the risk of failure. Kubernetes acknowledges these risks as part of life and offers ways to define how to react when these happen. To mitigate these risks, you need to configure Kubernetes resources, Quality of Service (QoS), and pod priority settings correctly to ensure stability and recoverability. Don't just hope for the best, define what happens when the ugly is at your doorstep.

1. Resource Requests and Limits for Databases

Databases are resource-intensive and sensitive to performance degradation, so setting appropriate CPU and memory requests/limits is crucial, especially keeping in mind that we will be handling state, which in reality removes elasticity. Dynamically adding replicas will increase the load on our system when scaling is required, as the new instances will need to be synced. But before diving deep, let's first define some good approaches to get reliable values.

Memory Considerations

Memory allocation for databases is critical since insufficient memory can lead to excessive swapping, slowing down performance, while over-allocating can waste valuable resources. Key factors to consider:

- Working Set Size (WSS): Measure the actively used memory by the database.

- Buffer Cache Usage: Monitor how efficiently the database caches data in memory.

- Peak Load Analysis: Identify memory spikes during high traffic periods.

- Garbage Collection & Memory Fragmentation: For databases like PostgreSQL and MongoDB, factor in memory management behaviors.

How to Determine Memory Resources

- Monitor

container_memory_working_set_bytesover time. - Use

quantile_over_time(0.5, container_memory_working_set_bytes{namespace="%s", container="%s"}[6h])to estimate a safe request value. You might want to use a higher quantile, but this will affect cost. - Use

quantile_over_time(0.999, container_memory_working_set_bytes{namespace="%s", container="%s"}[6h])to estimate a safe limit value. - Ensure that you calculate over some time with the actual load.

CPU Considerations

Databases often require consistent CPU resources, and unlike stateless applications, CPU throttling can significantly impact query performance and latency.

-

Baseline Utilization: Identify normal CPU usage using

sum(rate(container_cpu_usage_seconds_total[5m])). - Latency-Sensitive Workloads: If high query performance is required, avoid setting strict CPU limits.

- Parallel Processing: For multi-threaded databases (e.g., PostgreSQL), ensure enough CPU cores are available.

- Scaling Considerations: Vertical scaling (increasing CPU per instance) is often more effective than horizontal scaling due to sync overhead.

How to Determine CPU Resources

- Use

quantile_over_time(0.5, node_namespace_pod_container:container_cpu_usage_seconds_total:sum_irate{namespace="%s", container="%s"}[24h])to find a safe threshold. - Consider setting requests at the 90th percentile to prevent throttling while ensuring efficient resource allocation.

- Set CPU limits using

quantile_over_time(0.999, node_namespace_pod_container:container_cpu_usage_seconds_total:sum_irate{namespace="%s", container="%s"}[6h])to prevent excessive resource usage while allowing headroom for bursts.

Disk I/O Considerations

Databases rely heavily on disk performance, and slow I/O can severely degrade performance. Key aspects include:

- Read vs. Write Operations: Analyze workload characteristics (e.g., OLTP vs. OLAP).

-

Disk Latency: Use metrics like

node_disk_read/write_latency_secondsto assess disk performance. -

Storage Throughput: Monitor

rate(node_disk_bytes_read/write_total[5m])to determine IOPS requirements. - SSD vs. HDD: Use SSDs for low-latency and high-throughput workloads.

How to Determine Disk I/O Requirements

- Measure average and peak disk utilization over time.

- Ensure sustained disk throughput meets database requirements .

- Use provisioned IOPS storage (e.g., AWS EBS gp3/io1) for consistent performance.

Final Considerations

- Profile Database Workloads: Different databases (MySQL, PostgreSQL, MongoDB) have unique performance characteristics.

- Test Under Load: Simulate real traffic to fine-tune resource requests and limits.

- Monitor & Adjust: Continuously monitor resource usage and adjust based on observed trends.

By following these best practices, we can ensure stable, efficient, and performant database deployments without over-allocating resources or causing unexpected failures due to under-provisioning. Just make sure you are using some block storage for the actual state so that if a node dies and your workloads are rescheduled, their disks will follow them. Also, keep in mind that disks are AZ-locked.

2. QoS Class

Kubernetes assigns QoS classes based on resource settings:

- Guaranteed: Assigns the highest priority and prevents eviction due to resource pressure. Requires CPU and memory requests to match limits.

- Burstable: Allows flexibility but risks eviction under high cluster load. Suitable for less critical workloads.

- BestEffort: Most vulnerable to eviction. Not recommended for databases.

Recommendation: Run the exercise and calculate the values for CPU and Memory. Then start with the primary and assign resources that will have a Guaranteed workload. This means calculating the limit values for both CPU and Memory, giving some extra 20%, or at least rounding up those numbers to have the headroom and use the same exact numbers for the request values.

Replicas are simpler because you will have a number of them and you should start thinking of them as cattle. These should run as burstable workloads and you want to cut costs here. So use the exact values you got from the previous exercise.

3. Pod Priority and Preemption

When the cluster runs out of resources, Kubernetes evicts lower-priority pods first. To protect database pods, you should leverage a PriorityClass with a high value to ensure database pods are scheduled before lower-priority workloads. In reality, what we are doing here is defining how the cluster will do triage once the building is on fire. When PriorityClass is useful the "ugly" is not at our doorstep, it walked in the house. At this point it's not IF workloads will stop but WHICH workload has a higher probability of staying functional. And as always with probabilities dice are going to get rolled. What we are doing here is stacking the dice to try and minimize the fallout.

Example of a high-priority class:

apiVersion: scheduling.k8s.io/v1

kind: PriorityClass

metadata:

name: database-critical

value: 1000000

globalDefault: false

description: "Priority for critical database workloads"

Assign the priority class to database deployments, keeping in mind that the primary instance is more critical than replicas:

...

spec:

template:

spec:

priorityClassName: database-critical

Consider here that your PRIMARY pods are more important than your REPLICAS, and also acknowledge that probably not all your tenants are equal. These aspects of reality should be reflected here.

4. Anti-Affinity and Pod Disruption Budgets

Node and Zone Anti-Affinity: Spread database pods across nodes to avoid single points of failure.

To ensure high availability and resilience for database pods, you can use node anti-affinity and zone anti-affinity rules in Kubernetes. This prevents all database pods from being scheduled on the same node or within the same availability zone, reducing the risk of downtime due to node or zone failures.

...

spec:

affinity:

podAntiAffinity:

requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: my-database

topologyKey: "kubernetes.io/hostname" # Ensures pods are spread across different nodes

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 100

podAffinityTerm:

labelSelector:

matchLabels:

app: my-database

topologyKey: "topology.kubernetes.io/zone" # Prefer different zones

Node and Zone Anti-Affinity: Spread database pods across nodes to avoid single points of failure.

Pod Disruption Budget (PDB): Ensures at least one database pod remains available during voluntary disruptions.

apiVersion: policy/v1

kind: PodDisruptionBudget

metadata:

name: db-pdb

spec:

minAvailable: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: my-database

By carefully configuring Kubernetes resources, QoS, priority, and graceful shutdown mechanisms, you can prepare for the eventuality of the "ugly" and minimize disruptions to your database workloads.

Observability

Sample Prometheus rule regarding a generic app database that can be used as a reference.

apiVersion: monitoring.coreos.com/v1

kind: PrometheusRule

metadata:

name: app-postgresql

labels:

release: prometheus

app.kubernetes.io/component: metrics

spec:

groups:

- name: app-postgresql

rules:

- alert: PostgresqlDown

annotations:

description: Postgresql instance is down VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql down (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: pg_up{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} == 0

for: 0m

labels:

severity: critical

- alert: PrimaryPostgresqlRestarted

annotations:

description: Postgresql restarted VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql restarted (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: time() - process_start_time_seconds{namespace="backend", pod="app-postgresql-primary-0"} < 60

for: 2m

labels:

severity: critical

- alert: PostgresqlRestarted

annotations:

description: Postgresql restarted VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql restarted (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: time() - process_start_time_seconds{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} < 60

for: 0m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlRunningOutConnections

annotations:

description: Available VALUE VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Number of available connections less than 10% (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: (((sum(pg_settings_max_connections{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) by (server) - sum(pg_settings_superuser_reserved_connections{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) by (server)) - sum(pg_stat_activity_count{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) by (server)) / sum(pg_settings_max_connections{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) by (server)) * 100 < 10

for: 2m

labels:

component: database

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlExporterError

annotations:

description: Postgresql exporter is showing errors. A query may be buggy in query.yaml VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql exporter error (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: pg_exporter_last_scrape_error{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} > 0

for: 0m

labels:

severity: critical

- alert: PostgresqlTableNotAutoVacuumed

annotations:

description: Table {{ $labels.relname }} has not been auto vacuumed for 10 days VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql table not auto vacuumed (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: (pg_stat_user_tables_last_autovacuum{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} > 0) and (time() - pg_stat_user_tables_last_autovacuum{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) > 60 * 60 * 24 * 10

for: 0m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlTableNotAutoAnalyzed

annotations:

description: Table {{ $labels.relname }} has not been auto analyzed for 10 days VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql table not auto analyzed (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: (pg_stat_user_tables_last_autoanalyze{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} > 0) and (time() - pg_stat_user_tables_last_autoanalyze{namespace="backend", pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) > 24 * 60 * 60 * 10

for: 0m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlTooManyConnections

annotations:

description: PostgreSQL instance has too many connections (> 80%). VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql too many connections (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: sum by (instance, job, server) (pg_stat_activity_count{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) > min by (instance, job, server) (pg_settings_max_connections{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} * 0.8)

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlNotEnoughConnections

annotations:

description: PostgreSQL instance should have more connections (> 5) VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql not enough connections (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: sum by (datname) (pg_stat_activity_count{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*", datname!~"template.*|postgres|readme_to_recover"}) < 5

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlDeadLocks

annotations:

description: PostgreSQL has dead-locks VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql deadlocks (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: increase(pg_stat_database_deadlocks{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*", datname!~"template.*|postgres|readme_to_recover"}[1m]) > 5

for: 0m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlHighRollbackRate

annotations:

description: Ratio of transactions being aborted compared to committed is > 2 VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql high rollback rate (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: sum by (namespace,datname) ((rate(pg_stat_database_xact_rollback{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*",datname!~"template.*|postgres|readme_to_recover",datid!="0"}[3m]))) / (((rate(pg_stat_database_xact_rollback{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*",datname!~"template.*|postgres",datid!="0"}[3m])) + (rate(pg_stat_database_xact_commit{datname!~"template.*|postgres",datid!="0"}[3m])))) > 0.02

for: 0m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlCommitRateLow

annotations:

description: Postgresql seems to be processing very few transactions VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql commit rate low (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: rate(pg_stat_database_xact_commit{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*",datname!~"template.*|postgres|readme_to_recover"}[1m]) < 1

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlReplicationLag

annotations:

description: VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql replica is lagging (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: pg_replication_lag_seconds{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} > 2

for: 1m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlTooManyDeadTuples

annotations:

description: PostgreSQL dead tuples is too large VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql too many dead tuples (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: ((pg_stat_user_tables_n_dead_tup{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} > 5)) / (pg_stat_user_tables_n_live_tup{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} + pg_stat_user_tables_n_dead_tup{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}) >= 0.1

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlTooManyLocksAcquired

annotations:

description: Too many locks were acquired on the database. If this alert happens frequently, we may need to increase the postgres setting max_locks_per_transaction. VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql too many locks acquired (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: ((sum (pg_locks_count{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"})) / (pg_settings_max_locks_per_transaction{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"} * pg_settings_max_connections{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"})) > 0.20

for: 2m

labels:

severity: critical

- alert: PostgresqlLatency

annotations:

description: Postgres is running slow. VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql is lagging over 1 second (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: pg_stat_activity_max_tx_duration{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*",state="active"} > 1

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlCacheHitRate

annotations:

description: Postgres cache hit rate is very low. VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql is lagging over 1 second (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: 100 * (rate(pg_stat_database_blks_hit{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[2m]) / ((rate(pg_stat_database_blks_hit{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[2m]) + rate(pg_stat_database_blks_read{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[2m]))>0)) < 80

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlMemoryAvailable

annotations:

description: Postgres is using over 0.8 of available memory. VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql running out of available memory (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: sum by(pod,container)(container_memory_usage_bytes{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*", container!="POD",container!=""}) / sum by(pod,container)(kube_pod_container_resource_limits{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*",resource="memory"}) > 0.8

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

- alert: PostgresqlRequestedBufferCheckpoints

annotations:

description: PostgreSQL uses the buffer checkpoints to write the dirty buffers on disk, so it creates safe points for the Write Ahead Log (WAL). These checkpoints are scheduled periodically but also can be requested on-demand when the buffer runs out of space. A high number of requested checkpoints compared to the number of scheduled checkpoints can impact directly the performance of your PostgreSQL instance. To avoid this situation you could increase the database buffer size. VALUE = {{ $value }} LABELS = {{ $labels }}

summary: Postgresql is over using write buffer (instance {{ $labels.instance }})

expr: rate(pg_stat_bgwriter_checkpoints_req_total{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[5m]) / (rate(pg_stat_bgwriter_checkpoints_req_total{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[5m]) + rate(pg_stat_bgwriter_checkpoints_timed_total{namespace="backend",pod=~"app-postgresql-.*"}[5m])) * 100 > 0.8

for: 2m

labels:

severity: warning

If you need some business-related logic to be exposed and alert on, then you can use the metrics exporter and create a custom metric, eg:

pg_database:

metrics:

- name:

description: Name of the database

usage: LABEL

- size_bytes:

description: Size of the database in bytes

usage: GAUGE

query: SELECT pg_database.datname, pg_database_size(pg_database.datname) as bytes

FROM pg_database;

and then create an alert based on the particular metric. Try to keep in mind that these are queries that will run on the database every time Prometheus queries the exporter. So think carefully, do you need to have exact values or estimates? Leverage EXPLAIN ANALYZE to verify what you are doing and take a minute to think if this query MUST run on your primary database or on a replica.

pg_table:

metrics:

- name:

description: Name of the table

usage: LABEL

- row_count:

description: Estimated number of rows in the table

usage: GAUGE

query: >

SELECT relname AS name, reltuples::bigint AS row_count

FROM pg_class

JOIN pg_namespace ON pg_class.relnamespace = pg_namespace.oid

WHERE nspname NOT IN ('pg_catalog', 'information_schema') AND relkind = 'r';

Estimate vs. Exact: Uses reltuples from pg_class, which generate an estimation based on the last ANALYZE. This avoids a full COUNT(*), which might be expensive.

Performance Impact: This query is fast since it avoids scanning entire tables.

Primary vs. Replica: Ideally, run on a replica if available, as stats are not real-time but good enough for monitoring.

Stakeholders

Business: Justify, Estimate, and Monitor Costs

When working with business stakeholders, your main concerns will likely revolve around Premature Scaling and Infrastructure Cost Leverage. To align with their priorities: Justify why each step is necessary. Provide cost estimations, especially based on CPU and resource requirements. Demonstrate cost monitoring strategies to prevent budget overruns. Remember, business teams are balancing financial resources across multiple departments. They see infrastructure as an investment—make sure they understand the return. Explain how all these contribute to their feature matrix.

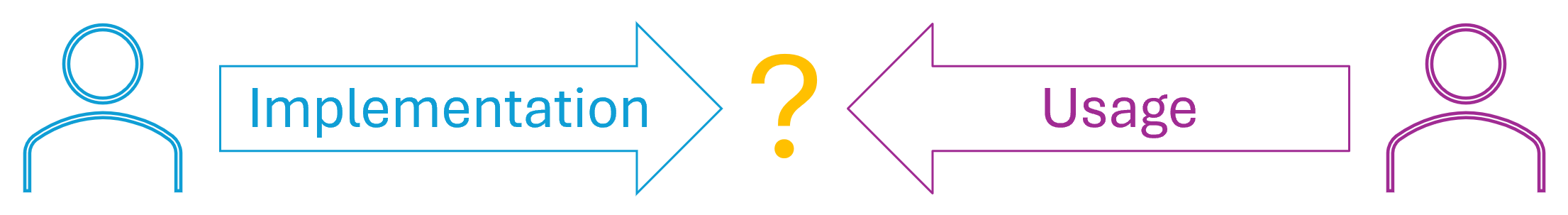

Developers: Observe, Adapt, and Abstract

Don't assume how developers work—observe, verify, and validate before introducing changes. To be an effective DevOps engineer: Understand their existing workflows before making recommendations. Build internal tooling that simplifies their processes. Abstract complexity, but recognize that it still exists—hiding it doesn't mean it disappears. Your goal is to empower developers with seamless tooling while ensuring operational efficiency under the hood.

Tools and more examples to work with developers.

devbox: Help developers set up their environment in a constant manner.

Justfile: Help standardize actions, especially the ones with friction. A good example of this is generating dynamic credentials for your engineering teams, consider the following solution that uses BitWarden to fetch some secrets that will be used for the next steps:

# Default recipes list

@default:

just --list

# Check if Bitwarden is unlocked and prompt for unlock if needed

# Returns the BW_SESSION token

_bw:

#!/usr/bin/env bash

# bw config server https://vault.bitwarden.eu

vault_status=$(bw status | jq -r '.status')

if [ $vault_status = "locked" ]

then

echo "