On Another World with You: The Romance of "Janet Planet"

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).The image is tough to see until our eyes adjust: a girl, not yet a teenager, perched on the edge of a bed, alone, ensconced in darkness, her head bisected by the edge of the frame. She’s looking. Is it at something, or for something? She gets up, walks outside, the deafening susurrus of cicadas all around her. She makes a call on a payphone, announces herself as Lacy. “I’m gonna kill myself,” she deadpans into the receiver. A pause. “I said I’m gonna kill myself if you don’t come get me.” She hangs up.This is the first sequence of Janet Planet (2024), the first film by Annie Baker—and it immediately exhibits the qualities of her formidable work as a playwright: the curious quiet, the felt time, the mordant sense of humor. Like Kenneth Lonergan before her, Baker is a celebrated stage dramatist with a particular affinity for American outcasts and a finely tuned ear for the halting, accidentally poetic ways they speak. And like Lonergan with You Can Count On Me (2000), she’s now made the leap to the screen with a dramatically taut, profoundly moving portrait of family life in a small town in the Northeastern United States. But whereas Lonergan only began to take formal risks with the structural gambits and sonic experimentation of his sophomore film, Margaret (2011), Baker’s cinematic vision is already quietly radical, fully formed, rich in life and detail.Lacy (Zoe Ziegler, also making her screen debut) is calling home from summer camp, where she’s been unable to make friends. She’s smart and curious in the way many eleven-year-olds are in real life but so few are in movies (Rory Culkin’s Rudy in You Can Count On Me is another exception). Behind big glasses, often in a cap and almost always with an oversized T-shirt slumping off her shoulders, Lacy is perceptive and hilarious (“You know what’s funny? Every moment of my life is hell”). She’s aware of the vast world around her (even if she doesn’t fully understand it) but especially self-aware of her place in it. She practices piano and plays alone with an assorted collection of figurines on a diorama stage in her bedroom. In the film’s opening, it’s not just that Lacy wants to leave camp. She wants to come home to her mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson).Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).Like Janet Rigsbee—onetime muse to Van Morrison, who nicknamed her “Janet Planet”—Lacy’s mother inspires with her intense gravitational pull. With Nicholson’s physicality—tall not only from a child’s vantage point, boasting the elongated limbs and sharp angles of a one-time ballet dancer—Janet is a towering presence, a magnetic enigma in billowy linen and a lopped-off haircut she could have given herself. She’s withholding, but with occasional bursts of surprising candor often reserved for just Lacy: “I know I’m not that beautiful,” she professes to her daughter. Janet is an acupuncturist and a lover and a friend and a searcher—what some might term a “free spirit”—not necessarily in that or any order; she is a single mother who doesn’t define herself entirely by having a child. Lacy’s whole universe, meanwhile, revolves around Janet.When she talks about other people’s movies, the idea of romance looms large for Baker, that grand intoxication with someone or something bigger than yourself. On James Ivory’s A Room with a View (1986): “[It] was my favorite movie when I was nine. And it really screwed with my head. It’s so over-the-top romantic, and I remember it made me dizzy with desire. I really expected nothing less than Julian Sands in a Tuscan poppy field from my adult romantic life.” On Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s Frances Ha (2012): “It’s not a boy-girl romance or a girl-girl romance but a romance between the title character and her capital-S Self.” Janet Planet is an unconventional romance of its own. It’s a rare cinematic portrait of a daughter’s total infatuation with her mother.Janet treats and talks to Lacy more like a peer than a kid, throwing out terms like “migraine” and “cult” in conversation without realizing these to be grown-up things Lacy wouldn’t already know about. When Lacy asks an invasive personal question to Wayne (Will Patton), Janet’s boyfriend at the start of the picture, her mother doesn’t reprimand her; in fact, she doesn’t say anything. Janet lets Lacy sleep in bed next to her, against Wayne’s advice. As they lie next to each other one night, Lacy wants to hold and to have her mother, literally asking for a piece of her. In return she gets a single hair Janet plucks from her head, which we see from Lacy’s perspective, held up against the dark night, glistening in moonlight.Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).Their troubled romance unfolds within a vaulted-ceiling two-story wooden house in a rural stretch of Western Massachusetts. Much of Baker’s work as a playwright has focused on left-of-center communities on either coast of the US, places rich in history and full of spiritual seekers: the fictional Shirley, Vermont,

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

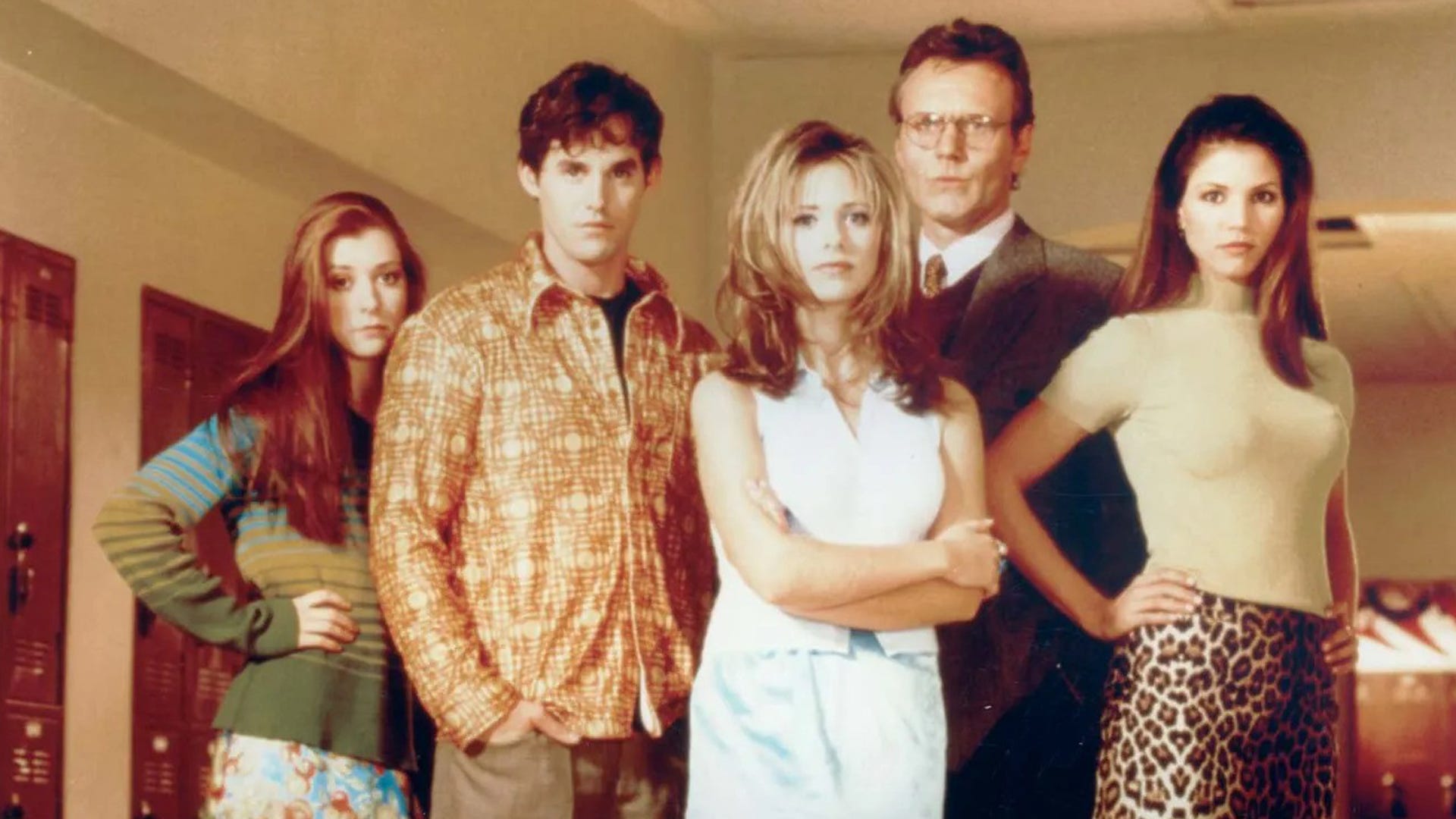

The image is tough to see until our eyes adjust: a girl, not yet a teenager, perched on the edge of a bed, alone, ensconced in darkness, her head bisected by the edge of the frame. She’s looking. Is it at something, or for something? She gets up, walks outside, the deafening susurrus of cicadas all around her. She makes a call on a payphone, announces herself as Lacy. “I’m gonna kill myself,” she deadpans into the receiver. A pause. “I said I’m gonna kill myself if you don’t come get me.” She hangs up.

This is the first sequence of Janet Planet (2024), the first film by Annie Baker—and it immediately exhibits the qualities of her formidable work as a playwright: the curious quiet, the felt time, the mordant sense of humor. Like Kenneth Lonergan before her, Baker is a celebrated stage dramatist with a particular affinity for American outcasts and a finely tuned ear for the halting, accidentally poetic ways they speak. And like Lonergan with You Can Count On Me (2000), she’s now made the leap to the screen with a dramatically taut, profoundly moving portrait of family life in a small town in the Northeastern United States. But whereas Lonergan only began to take formal risks with the structural gambits and sonic experimentation of his sophomore film, Margaret (2011), Baker’s cinematic vision is already quietly radical, fully formed, rich in life and detail.

Lacy (Zoe Ziegler, also making her screen debut) is calling home from summer camp, where she’s been unable to make friends. She’s smart and curious in the way many eleven-year-olds are in real life but so few are in movies (Rory Culkin’s Rudy in You Can Count On Me is another exception). Behind big glasses, often in a cap and almost always with an oversized T-shirt slumping off her shoulders, Lacy is perceptive and hilarious (“You know what’s funny? Every moment of my life is hell”). She’s aware of the vast world around her (even if she doesn’t fully understand it) but especially self-aware of her place in it. She practices piano and plays alone with an assorted collection of figurines on a diorama stage in her bedroom. In the film’s opening, it’s not just that Lacy wants to leave camp. She wants to come home to her mother, Janet (Julianne Nicholson).

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

Like Janet Rigsbee—onetime muse to Van Morrison, who nicknamed her “Janet Planet”—Lacy’s mother inspires with her intense gravitational pull. With Nicholson’s physicality—tall not only from a child’s vantage point, boasting the elongated limbs and sharp angles of a one-time ballet dancer—Janet is a towering presence, a magnetic enigma in billowy linen and a lopped-off haircut she could have given herself. She’s withholding, but with occasional bursts of surprising candor often reserved for just Lacy: “I know I’m not that beautiful,” she professes to her daughter. Janet is an acupuncturist and a lover and a friend and a searcher—what some might term a “free spirit”—not necessarily in that or any order; she is a single mother who doesn’t define herself entirely by having a child. Lacy’s whole universe, meanwhile, revolves around Janet.

When she talks about other people’s movies, the idea of romance looms large for Baker, that grand intoxication with someone or something bigger than yourself. On James Ivory’s A Room with a View (1986): “[It] was my favorite movie when I was nine. And it really screwed with my head. It’s so over-the-top romantic, and I remember it made me dizzy with desire. I really expected nothing less than Julian Sands in a Tuscan poppy field from my adult romantic life.” On Noah Baumbach and Greta Gerwig’s Frances Ha (2012): “It’s not a boy-girl romance or a girl-girl romance but a romance between the title character and her capital-S Self.” Janet Planet is an unconventional romance of its own. It’s a rare cinematic portrait of a daughter’s total infatuation with her mother.

Janet treats and talks to Lacy more like a peer than a kid, throwing out terms like “migraine” and “cult” in conversation without realizing these to be grown-up things Lacy wouldn’t already know about. When Lacy asks an invasive personal question to Wayne (Will Patton), Janet’s boyfriend at the start of the picture, her mother doesn’t reprimand her; in fact, she doesn’t say anything. Janet lets Lacy sleep in bed next to her, against Wayne’s advice. As they lie next to each other one night, Lacy wants to hold and to have her mother, literally asking for a piece of her. In return she gets a single hair Janet plucks from her head, which we see from Lacy’s perspective, held up against the dark night, glistening in moonlight.

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

Their troubled romance unfolds within a vaulted-ceiling two-story wooden house in a rural stretch of Western Massachusetts. Much of Baker’s work as a playwright has focused on left-of-center communities on either coast of the US, places rich in history and full of spiritual seekers: the fictional Shirley, Vermont, of her first cycle of plays (2008–10); the Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, of John (2015); the Northern California healing clinic of Infinite Life (2023). (The one exception is The Antipodes, 2017, set in the purgatorial abyss of a room of writers and storytellers; or: Los Angeles.) The setting fills out Janet Planet with its remaining principal characters—a struggling actress, a mysterious theater director—whose presence gives the picture both its organizing structure and its conflict. Baker divides the film into chapters (complete with title cards) in the way Lacy herself might define the different eras of this seemingly mundane but deceptively pivotal summer in her life: by these adult strangers drifting in and out of her mother’s orbit.

First there’s Wayne, the boyfriend, a laconic single father of two with a fury bubbling underneath, who Lacy comes home one day to find shirtless in the living room—dancing? practicing tai chi? After a crippling headache he claims Janet “transferred” onto him, Wayne erupts at Lacy’s persistent questioning, yelling her out of the room and slamming the door, separating her from her mother. Janet asks Lacy what she should do after the outburst. “I think you should break up with him.” (And she does.) Then comes Regina (Sophie Okonedo), an old friend of Janet’s who almost magically appears as an actor in an alfresco puppet show Lacy and Janet attend. Between roles and escaping a break-up from the cultish troupe director, Avi (Elias Koteas), she crashes in Janet and Lacy’s loft. Before long, old wounds and charged dynamics spill out during a dark night of the soul, and suddenly Regina is gone.

This is the tension at the heart of Janet Planet: Lacy’s constant fight for Janet's attention and affection, an insular, private two-person dynamic threatened and irrevocably changed by the inevitable appearance of outside forces. (This situates Janet Planet narratively alongside a handful of other great 21st-century films that explore a similar structural conflict: Everyone Else (2009) with a romantic couple; Ghost World (2001) and Frances Ha (2012) with female friendships.) Baker literalizes this idea of the encroaching invader at the start of Regina’s chapter: combing her daughter’s hair, Janet spots a tick and lets a freaked-out Lacy burn the parasite with a match. When Janet first sees Regina at the puppet performance, Baker and cinematographer Maria von Hausswolff position mother and daughter together in the center of the image; in the subsequent shots of Janet and Regina’s reunion, Lacy is already pushed aside to the corners of the frame.

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

Here is a portrait of childhood as an incomplete, ever-expanding (but no more clarifying) view of the world. Lacy isn’t privy to everything happening around her, and Baker ensures we aren’t either. When Janet and Regina catch up, Lacy eavesdrops, and we too can only half-hear their muffled voices in the other room. Only when they come into earshot do we pick up some crucial backstory about Janet and an ex (Lacy’s father?) who “moved to Mexico to be closer to his grandchildren” and a “Holocaust survivor dad.” When Avi later comes to talk with Regina, we see (and again don’t hear) them from Lacy’s perspective, her bedroom window slightly open, the pane partially obstructing the view. Lives in bits and pieces.

In one bravura set piece, Janet and Regina take a hallucinogenic. They talk, the drug loosening their inhibition, and the trip quickly sours, elucidating why there may have been a falling out in the first place. (Regina to Janet: “Objectively you do make bad decisions.”) It’s the kind of scene that could play as “theatrical” on the page—two people in a room trading dialogue, confronting their pasts. But Baker makes several arresting visual and aural choices: the lopped off framing of Janet and Regina lying next to each other; the use of Beverly Glenn-Copland’s “Ever New” (one of many pitch-perfect needle drops on the picture’s all-diegetic soundtrack). Baker lets this sequence play out for several minutes, allowing us to think that Janet and Regina are alone in the room, only to have Lacy pop up into the frame and reveal she’s been sitting next to them all along. A great visual gag, a telling bit of characterization, and a shrewd use of perspective, all at once.

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

Baker doesn’t do anything so simplistic as give us a “child’s-eye view” of the world, but she regularly obfuscates what we see and know throughout the film. Janet Planet is a period piece, but there’s no card to announce this at the outset. Baker instead offers only the hints of costume, production design, and pop culture in the background: Firehouse’s “Don’t Treat Me Bad” wafting from the radio at an ice cream stand, the theme song of “Clarissa Explains It All” coming off a TV set. (The title Janet Planet even feels like it could be a Nickelodeon show from that era.) There are the passing references in the dialogue: Wayne’s unseen son lives “In California. And Iraq.” (But then, which phase of that conflict?) It’s only after Regina has departed that we see a date. An unfamiliar man hastily packs Regina’s things and tears away the New Yorker cover she had affixed to a wall with the date: 1991. Only a fragment is left behind.

Avi reemerges for the third and final character chapter, having developed an affinity with Janet that Lacy (and we) did not see. He has dinner with both mother and daughter, speaking to Lacy like Janet does, as an adult. (A question to the table: “So we’re in agreement that before the universe existed there was nothing?”) On the day Lacy is due back at school, an illness comes on at the bus stop, prolonging her summer break by a day. And then another. Lacy lies under the dining table as Janet offers her the option of taking antibiotics—of course she makes this her daughter’s choice. Baker keeps the camera on the ground, only Janet’s freckled legs in the frame until she bends down so they can see each other.

Lacy stays home with cheese blintzes and her figurines while Janet and Avi go on a picnic. He reads to Janet, from Rilke’s “Elegy IV”; Lacy plays in her room. For the first time in the film, Baker cuts back and forth between Janet and Lacy in separate spaces at the same point in time. It’s a cosmic moment, mother and daughter seeming to look at each other though miles apart. Lacy closes her eyes. And something magical happens: Avi disappears, gone from the picture and Janet and Lacy’s lives in an instant. Directing her miniature diorama play, Lacy has shuffled the puppet theater director off stage. For this moment at least, with the psychic power of imagination and art, Lacy has won the battle for her mother; Janet returns home to her daughter.

Janet Planet (Annie Baker, 2024).

Despite her celebrated career in the theater, movies have always loomed large for Baker. Her 2013 play, The Flick—a snapshot of the lives of the employees of a Western Massachusetts movie theater—is, as of this writing, the definitive fictional portrait of contemporary cinephilia in any medium, centered around that gulf between the rapturous magic of the big screen and the humdrum realities of everyday life. She’s a consummate lover of cinema who has spoken and written eloquently on the films of Ingmar Bergman and Éric Rohmer, among many others, threads of which are woven into an entirely new quilt in Janet Planet. With the figurines in Lacy’s bedroom, it’s hard not to think of Fanny and Alexander (1982), Baker’s own favorite movie about childhood. (She writes of it: “The statues and the toy angels and the clocks and the puppets and the lamps… They’re all watching Alexander, the whole movie.”) Autumn Sonata (1978) likewise takes as its subject the tempestuous relationship between an ambivalent mother and a yearning daughter. With the narrative structured around Lacy’s fraught summer vacation, the mind drifts back to those anxious summer holidays in La Collectionneuse (1967), Claire’s Knee (1970), Pauline at the Beach (1983), The Green Ray (1986), A Summer’s Tale (1996), and the prologue of A Tale of Winter (1992).

Other films ultimately come to mind, even if they’re not deliberate reference points of Baker’s: Lucrecia Martel’s La ciénaga (2001) is a similarly galvanizing debut with its own sui generis cinematic language and defiant use of limited perspective. Richard Linklater’s Slacker (1990) is another early-career work that marries a genuine love of eccentric character with an intense formal rigor. But with this miracle of a movie, Baker has made something fully, uniquely her own, at once an extension of her stage work and an entirely new venture. Janet Planet could be described as a coming-of-age film, but it reveals something, in subject and form, much more profound: a coming-to-understanding, that maybe the things we idolize and romanticize in our youth—whether they be parents or works of art—don’t meet our lofty expectations and fantasies. But the reality can be something equally—and perhaps even more—beautiful.

The final section of Janet Planet is the only one not titled after a love interest or friend; “The Fall” marks the first point in the picture that Lacy’s time isn’t expressly delimited by another adult. Lacy finally gets on the bus and returns to school; we watch Janet watch her go. We don’t see anything of sixth grade, though. In the next scene, we’re back with Janet and Lacy together, heading to a local community dance night. Lacy watches from the sidelines as Janet do-see-does from partner to partner, a dizzying array of new adult interlopers to consider. We’re a long way from the first image: Lacy is now in the center of the frame, fully lit. An unseen man sits next to her, asks if she’s alone. “I’m here with my mom.” He asks if she wants to dance. Lacy demurs, just keeps watching. “Are you sure?” And she isn’t sure, but—just maybe—soon will be ready to join the dance herself.