Now the Free Press touts religion as filling our “god-shaped hole”

Yesterday we saw Ross Douthat helpfully advising New York Times readers how to find the “right” religion (nonbelief doesn’t count as faith); and today we find the Free Press touting religion by showing how “finding God” transformed the lives of nonbelievers for the better. (Note the implication that God is out there to be found!) … Continue reading Now the Free Press touts religion as filling our “god-shaped hole”

Yesterday we saw Ross Douthat helpfully advising New York Times readers how to find the “right” religion (nonbelief doesn’t count as faith); and today we find the Free Press touting religion by showing how “finding God” transformed the lives of nonbelievers for the better. (Note the implication that God is out there to be found!)

Rather than discuss the waning of religion in the West—something that Douthat avoided, too—Savodnik, an editor of the Free Press, simply tells the stories of a few notables who became religious and how much solace the conversion gave them. These are anecdotes, not a documentation of either the waning of religion or the overall benefits of religion to society. But, added together, they paint a picture of religion as something that people need, and something that will fill our “god-shaped” hole—our need to believe in the supernatural to give meaning to our lives. As I’ve said, I have no doubt that some people really can be helped by believing; Ayaan Hirsi Ali, whose crippling depression was cured by embracing Christianity, comes to mind. But what these anecdotes don’t convince me of is that we all need religion and would be better off following the people in the article (except for Dawkins).

Further, the piece doesn’t address the problem of forcing yourself to believe something that you’ve already rejected as false. I am not sure how Hirsi Ali, a former atheist, got herself to believe in the reality of Christianity (the status of Jesus as God/Son of God, the Resurrection, etc.), but of course people who reject something can really come to believe it if it’s important to believe it. (See Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four.)

The notion that this article is slanted towards getting people to believe is buttressed by its unfair and snarky treatment of Richard Dawkins, an atheist who is lumped in with the “believers’ just to show how hollow his idea of being a “cultural Christian” is.

Why am I highlighting this article, as I did Douthat’s yesterday? It’s because I sense that vocal liberals are now trying to push belief on the rest of us, asserting that our lives are empty without faith. I’m not sure why that’s true, and will let the readers give their hypotheses below. The Free Press may be soft on religion because its founder, Bari Weiss, is an observant Jew, and her partner, Nellie Bowles, converted when the got married. But that’s just a speculation. However, I’d expect a journalistic venue that touts rationality to at least counter an article like the one below with one showing how intellectuals benefited by giving up their belief in God.

Click the headline below if you have a subscription, or find the article archived here.

I’ll just list the nonbelievers or “searchers” whose lives suddenly improved when they settled on a given faith, and then add a quote from the article. Note that the photos of the converts (and Dawkins, too) are surrounded by halos. First, the point of the article:

But something profound is happening. Instead of smirking at religion, some of our most important philosophers, novelists, and public intellectuals are now reassessing their contempt for it. They are wondering if they might have missed something. Religion, the historian Niall Ferguson told me, “provides ethical immunity to the false religions of Lenin and Hitler.”

There is something inevitable about this reassessment, Jonathan Haidt, the prominent New York University psychologist and best-selling author, told me. (Haidt’s books include The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion.) “There is a God-shaped hole in every human heart, and I believe it was put there by evolution,” he said. He was alluding to the seventeenth-century French philosopher Blaise Pascal, who wrote extensively on the nature of faith.

“We evolved in a long period of group versus group conflict and violence, and we evolved a capacity to make a sacred circle and then bind ourselves to others in a way that creates a strong community,” Haidt told me.

Ferguson added that “you can’t organize a society on the basis of atheism.”

“It’s fine for a small group of people to say, ‘We’re atheist, we’re opting out,’ ” he said, “but, in effect, that depends on everyone else carrying on. If everyone else says, ‘We’re out,’ then you quickly descend into a maelstrom like Raskolnikov’s nightmare”—in which Rodion Raskolnikov, the protagonist of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment, envisions a world consumed by nihilism and atomism tearing itself apart. “The fascinating thing about the nightmare is that it reads, to anyone who has been through the twentieth century, like a kind of prophecy.””

I’m surprised that Haidt, whose religiosity I don’t know, would tout religion here and in other places. I thought he was more rational than that. And Ferguson’s claim that atheist societies can’t function because of nihilism is flat wrong. Look at Scandinavia, for crying out loud!

On to the believers:

Matthew Crawford. He was a “a searcher” who converted to the Anglican Church after he met an Anglican woman (whom he later married) while giving a talk in a church. He says this of being an Anglican:

“I liken it sometimes to a psychedelic experience,” Crawford said. “You feel like you’ve gained access to some layer of reality, but you just weren’t seeing it.” He meant God, but he also seemed to be talking about his wife.

“A lot of very thoughtful people who once believed reason and science could explain everything—why we’re here, what comes after we’re gone, what it all means—are now feeling a genuine hunger for something more,” he said.

“There has to be a larger order that comprehends us and makes a demand on us,” Crawford added. “It’s clear that we can’t live without a sense of meaning beyond ourselves.”’

Yes, but that “sense of meaning beyond ourselves” can include our love of friends and family, our work, our avocations, and, for me, science. You don’t need God to get a “sense of meaning.”

Joe Rogan and Russell Brand.

In February 2024, podcaster Joe Rogan, in a conversation about the sorry state of America’s youth with New York Jets quarterback Aaron Rodgers, said: “We need Jesus.” Not five years earlier, Rogan had hosted Richard Dawkins on his show and poked fun at Christians.

In April, the comedian Russell Brand—who has emerged in recent years as a voice of the counterculture and amassed an audience of more than 11 million on X—announced that he was about to be baptized. “I know a lot of people are cynical about the increasing interest in Christianity and the return to God but, to me, it’s obvious. As meaning deteriorates in the modern world, as our value systems and institutions crumble, all of us become increasingly aware that there is this eerily familiar awakening and beckoning figure that we’ve all known all our lives within us and around us. For me, it’s very exciting.”

I guess the Jews, Hindus, and Muslims are deficient because they don’t, according to Rogan, need Jesus. As for Brand, well, he’s a loose cannon and I take no lesson from his conversion.

Jordan Peterson. What can you say about a guy who can’t even explain clearly what he believes? Now, however, he’s decided that God is “hyper-real”—whatever that means.

Then in July, Elon Musk—the former “atheist hero,” the king of electric vehicles and space exploration, the champion of free expression—sat down with Jordan Peterson, the Canadian psychologist who has studied the intersection of religion and ideology, to discuss God. “I’m actually a big believer in the principles of Christianity,” Musk said. Soon after, Musk took to X to pronounce that “unless there is more bravery to stand up for what is fair and right, Christianity will perish.”

Then, last month, Peterson’s book We Who Wrestle with God: Perceptions of the Divine was published. Peterson had always avoided saying whether he believed in a higher power. Now, sporting a jacket emblazoned with the Calvary cross, he was pushing back against the new atheists. “I would say God is hyper-real,” Peterson said in a recent interview with Ben Shapiro promoting the book. “God is the reality upon which all reality depends.”

I’d like to ask Dr. Peterson why he is so sure that there even is a god. But all I’d get was his usual preparation of word salad.

Paul Kingsnorth. Here’s another searcher who found “true” religion: Romanian Orthodoxy after he was at first a Zen Buddhist and then a “neopagan”:

When I asked Kingsnorth why he embraced Christianity after having steered clear of it for his entire life, he said it wasn’t a “rational choice.”

“If you ever meet a holy person, you look at them and you think, Wow, that’s really something—you know, I would love to be like that,” he said. “How does that happen?”

“The culture,” by contrast, “doesn’t have any spiritual heart at all. It’s as if we think we can just junk thousands of years of religious culture, religious art, religious music, chuck it all out the window, and we’re just building and creating junk.”

He said the story we’ve been telling ourselves for the last 100 years or so, of endless progress and secularism and the triumph of reason, is now “at some kind of tipping point.” Our great “religious reawakening” is just people “finding their way back to something that they never expected to find their way back to.”

Here we have another person asserting that we’re at a “tipping point”. Perhaps that’s true, but what’s the evidence? And, if we advance in rationality and discard religion, that doesn’t mean that we have to chuck out all the art and music that was inspired by religion. Modern art and music are not inspired by religion, and yet the culture survives. You can admire Chartres without having to be a Christian. Yes, it’s a beautiful testament, but one of a pervasive delusion.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali. We’ve hear her story before: first a Muslim, then an atheist and then, after severe depression, found relief in Christianity, and embraces its empirical tenets, like the existence, meaning, and resurrection of Jesus.

Quotes:

Hirsi Ali recalled a conversation she had with the British philosopher Roger Scruton shortly before he died in 2020. “I was telling him about my depression,” Hirsi Ali said of Scruton, who belonged to the Church of England, “and he said, ‘If you don’t believe in God, at least believe in beauty.’ ” Mozart, opera, church hymns—they were a way out of the dark, she said. She couldn’t help but be moved by something Scruton said: “The greatest works of art have been inspired by some connection to God.”

Scruton is dead wrong here. What was Picasso’s or Monet’s connection to God? They were atheists! See a longer list here. And you can find a list of atheist composers and musicians here; they include Bizet, Ravel, Saint-Saëns, Shostakovich, and Verdi. And don’t forget that before about 1850, nobody would admit that they were atheists, so the list is surely longer. Scruton is simply full of it. But I digress; back to Hirsi Ali

“It’s been a year, 15 months”—since embracing her new faith—“and I still feel almost miraculous,” Hirsi Ali told me.

On September 1, Hirsi Ali and Ferguson and their sons were baptized. “I had a spiritual void in my life, and Ayaan certainly did,” Ferguson said. “Her discovery of a Christian God saved her.”

When I asked Hirsi Ali and Ferguson whether their faith was real or just a political balm meant to combat the “cult of power”—whether they were, as Dawkins said, “theological Christians” or a “cultural” ones—they said their faith was “genuine.”

I do believe them, and I’m find with Hirsi Ali embracing Christianity if it helped relieve her crippling depression. But I don’t like her proselytizing about it, implying that others might find similar relief.

Jordan Hall. Another searcher who felt empty but filled his god-shaped hole by joining the Swannanoa Christian Church in North Carolina.

The emptiness he’d spent years fleeing was not just his emptiness, as far as he could tell. It was society-wide.

“We’re actually facing a clear and present danger,” Hall said. “It’s cultural termination, and it’s almost certainly going to come to a catastrophic end soon.”

He meant plummeting birth rates, imploding families, relationships that were pale shadows of real relationships—digitized friendship and love as opposed to genuine interactions between people who actually care about and know each other. “The horrifying brokenness of people.”

Well, you could say this about nearly every era, so the times we’re going through (with a lot of the horror that we face caused by religion) does not suggest, at least to me, that religion will fix the world. What religion? Islam? Christianity? Judaism? Or will the world be better if everyone embraces the faith they find congenial? That hasn’t worked so well if the world really is broken?

Finally,

Richard Dawkins, who also sports a halo:

The piece does everything it can to make Dawkins not only look bad, but also look as if he’s a quasi-Christian:

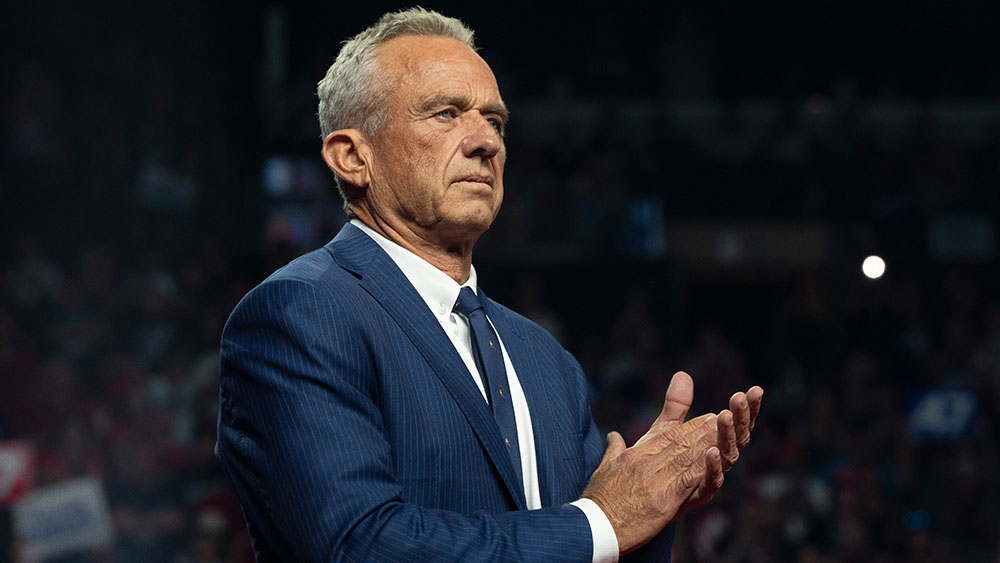

When we spoke—via Zoom, Dawkins in a brightly lit room at home in Oxford, England—he was a tad irritable. He was in a navy blazer, and there was a wall of books behind him, and he seemed a little exasperated with all the God talk.

Dawkins had created a furor when, in the midst of the often violent, pro-Hamas demonstrations in London and New York and elsewhere, he appeared on a British radio program and called himself a “cultural Christian.” He went on to say, “I sort of feel at home in the Christian ethos, I feel that we are a Christian country in that sense.”

“I rather regret” having said all that now, he told me.

Yes, he caused a furor, but I don’t mind much. I am, after all, a cultural Jew, even though I’m not in a Jewish country. It’s just the tribe you belong to, just like the country you belong to, and you don’t have to believe a word of religions tenets, as neither Richard nor I do.

And the rest:

Dawkins underscored that he, like Sam Harris, is still very much an atheist. He did not see any contradiction in saying, as he had to Rachel Johnson on the Leading Britain’s Conversation (LBC) radio show, that he was “happy” with the number of Christians declining in Britain and that he “would not be happy if we lost all our cathedrals and our beautiful parish churches.”

“The tendency you’re talking about,” he told me, alluding to Hirsi Ali, “is, I think, mostly people who don’t necessarily believe Jesus was the son of God or born of a virgin, or rose from the dead, but nevertheless think that Christianity is a good thing, that Christianity would benefit the world if more people believed it, that Christianity might be the sort of basis for a lot of what’s good about Western civilization.”

And yet, Dawkins did admit he was worried about losing the world that had been bequeathed to us by Christianity. “If we substituted any alternative religion,” he said in his April interview, “that would be truly dreadful.”

It wasn’t just about the danger of what was coming. It was about what we were losing, or might lose.

“Some of the greatest music ever written is church music, music inspired by Christianity,” he told me, echoing Roger Scruton. J.S. Bach would never have composed his Mass in B Minor—with all those violins, cellos, sopranos, and tenors weaving together, pointing us toward the heavens—without the divine, he said. Nor would Dostoevsky, as Paul Kingsnorth said, have written The Brothers Karamazov had he not been a believer. Had the world not been changed in countless unbelievable ways by that art? Had that art not changed us?

When I mentioned Dawkins’s distinction between cultural and theological Christianity to Kingsnorth, he said he thought Dawkins was deliberately sidestepping a deeper conversation about the nature of belief.

“As far as he’s concerned, it’s just chemicals in the brain,” Kingsnorth said of Dawkins. “But the reason religion persists is people keep having experiences of God, and Dawkins doesn’t seem to want to deal with that.”

Admiration for the artistry of churches, mosques and religious paintings does not constitute support for a psychological need to be religious, much less for the truth of religion. Seriously, Richard should write an essay about that misconception, which I call “The Argument from Cathedrals.” And I bet the “alternative religion” he’s thinking about is probably Islam. I wouldn’t want to live in an America that had been founded by Islamists rather than Christians, either, but that speaks to how the religions make people behave rather than to their truth.

As for Kingsnorth, he’s just wrong: religion is indeed chemicals in the brain. And really, the “experiences of God” that people have consist largely of what you get from being proselytized. There are many ways one could show the existence of God (stars spelling out Christian words, prayers being answered for Christians alone, etc.), but people’s “experience of religion” is not convincing evidence, especially given the way that people become religious. Have you ever seen something like this?

These people are having “experiences” of god so intense they’re speaking in tongues. (I love glossolalia!). This is social contagion, and you can see similar things at football games.

Again, I’m floating the idea that liberals and intellectuals are pushing the idea that we have to go back to religion for our own and society’s good. I don’t know why—perhaps because times are rough now, and God is the Biggest Coughdrop. But times will get better, and religion, at least in the West, will continue to wane.