Harvard paid $27 for a Magna Carta copy in 1946. It’s actually an original.

Even at $451 in today’s dollars, that’s still a steal. The post Harvard paid $27 for a Magna Carta copy in 1946. It’s actually an original. appeared first on Popular Science.

In 1946, Harvard Law School purchased an early copy of the Magna Carta for $27.50. Even adjusting to about $451 in today’s valuation, the historic document described as “somewhat rubbed and damp-stained” was a pretty solid deal. Initial estimates dated the artifact to 1327, just 27 years after King Edward I’s initial proclamation.

For decades, Harvard’s rare edition of the seminal governing document offered a potent written symbol of society’s journey towards recognizing inalienable human rights—but a recent reevaluation has shocked historians, as well as the document’s current owners. It turns out the university’s Magna Carta “copy” is actually one of now seven original manuscripts penned in 1300.

“This is a fantastic discovery,” David Carpenter, a medieval historian at King’s College London said in the announcement from Harvard Law School. “[It] deserves celebration, not as some mere copy, stained and faded, but as an original of one of the most significant documents in world constitutional history…”

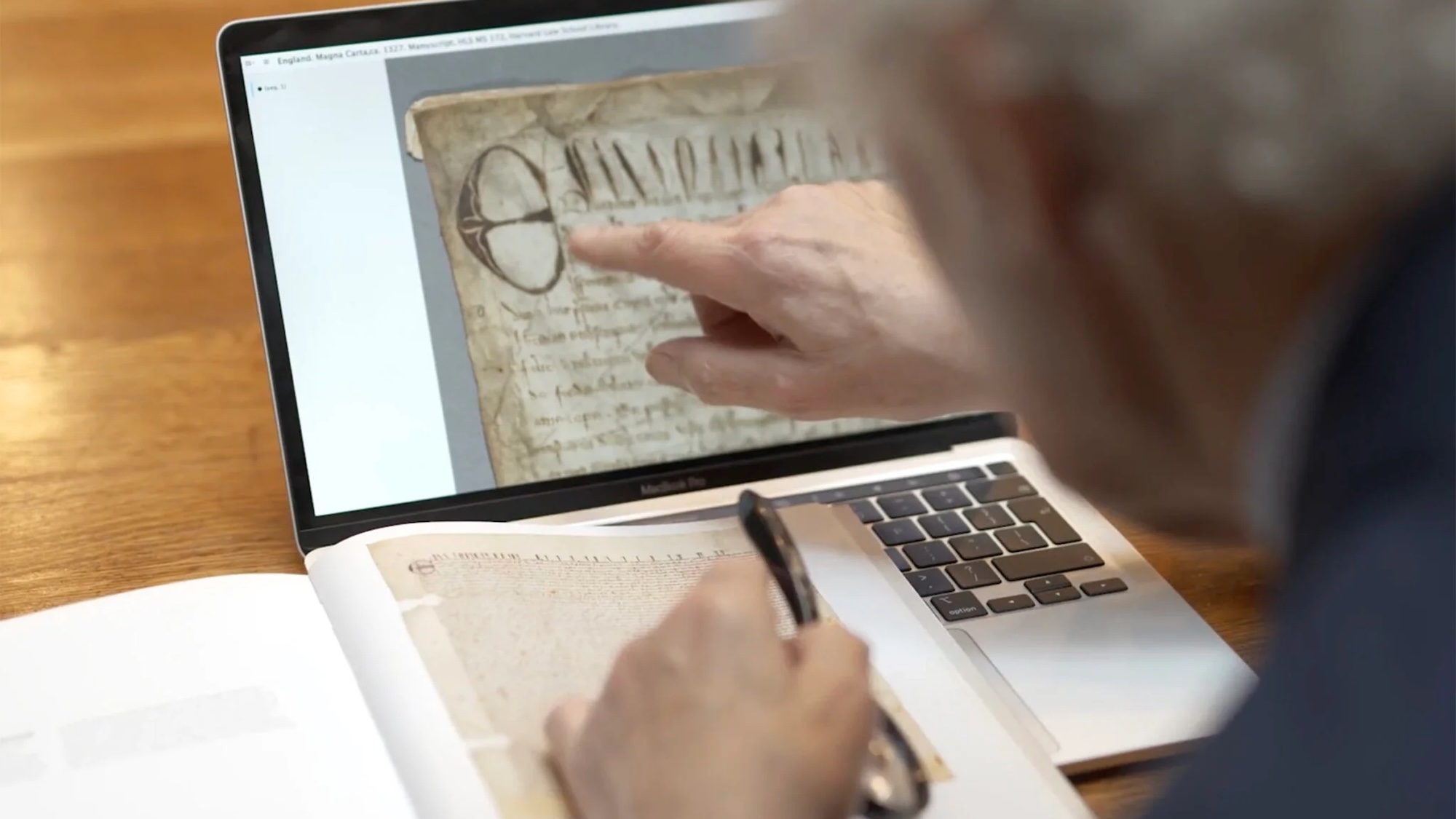

Carpenter is a major reason the document received a fresh examination. While recently perusing unofficial Magna Carta copies online, he paused on the law school’s digitized version on its website. Although the archive listed it as a copy, certain aspects stuck out to him. For one, its described dimensions of 489 by 473 millimeters (about 19.25 by 18.6 inches) matched those of the six previously confirmed originals. Then there was the penmanship itself—particularly the large capital “E” on the first word, “Edwardus,” as well as the initial line’s noticeably elongated lettering.

Carpenter and colleagues then used UV lights and spectral imaging to compare the Harvard edition with the six originals. Any textual variations between a supposed “copy” and the real documents would prove it to be an unauthorized later edition.

According to Carpenter, Harvard’s Magna Carta passed “with flying colors.”“This uniformity provides new evidence for Magna Carta’s status in the eyes of contemporaries. The text had to be correct,” he said.

After reviewing additional historical accounts about the few remaining original documents, Carpenter believes Harvard’s edition to be a long-lost Magna Carta originally presented to a former parliamentary borough in Westmorland, England. That variant eventually was put up for auction in 1945 by Forster “Sammy” Maynard, an air vice-marshal and former World War I flying ace. Maynard previously inherited the document from the archives of leading 18th century abolitionists, Thomas and John Clarkson. One of the Clarksons likely received the Magna Carta at some point in the early 1800s from William Lowther, the hereditary lord of Appleby manor.

“Given where it is, given present problems over liberties, over the sense of constitutional tradition in America, you couldn’t invent a provenance that was more wonderful than this,” said Nicholas Vincent, a collaborator on the reevaluation project and a medieval historian at the University of East Anglia.

“The work we do in the law, and pass on to new generations of students, is not simply the consistent application of logical principle,” explained Harvard Law School’s vice dean for Library and Information Services, Jonathan Zittrain. “It’s understanding how rare and precious self-governance across many differences can be, and how important it is to preserve and deliver upon it.”

The post Harvard paid $27 for a Magna Carta copy in 1946. It’s actually an original. appeared first on Popular Science.

.jpeg?#)