Air Travel Pollutes Relentlessly. Is Carbon Removal Part of the Solution?

It will take more than reducing emissions to solve climate change.

Tim Wenger is a senior editor at Matador Network. He’s filed work from four continents, reporting extensively from Southeast Asia, Mexico, and British Columbia, and his work often focuses on conservation, outdoor recreation, and sustainability.

For this story, Tim spoke with leaders across the travel and direct air capture (DAC) industries and compiled research from studies tracking the impacts of air travel on the environment. See more of his work at timwenger.net

In September 2021, the Swiss firm Climeworks inaugurated its carbon sequestration plant, Orca, near a geothermal power plant in Iceland. Orca uses renewable energy to extract CO₂ directly from the air, which is then stored underground in basalt rock formations where it mineralizes and becomes permanently trapped. The plant was the largest such operation when it opened.

The result is the opposite of what happens when you hop onto a plane and fly across the world. Rather than emissions going into the atmosphere, they’re coming out – and that makes CO₂ removal through direct air capture a potentially major way to make flying, and travel more broadly, less impactful on the environment.

“Greenhouse gases like CO₂ act like a blanket covering the Earth,” says Kate Dmytrenko, a spokesperson with Climeworks. “So just like a blanket traps body heat, these gases trap heat from the sun, preventing it from escaping back into space. As more gases accumulate, the Earth gets warmer – just like adding more blankets would make you hotter. So in the fight against climate change, the majority of our efforts, I’m talking 90 percent, needs to be focused on reducing the amount of CO₂ that we’re putting into the atmosphere.”

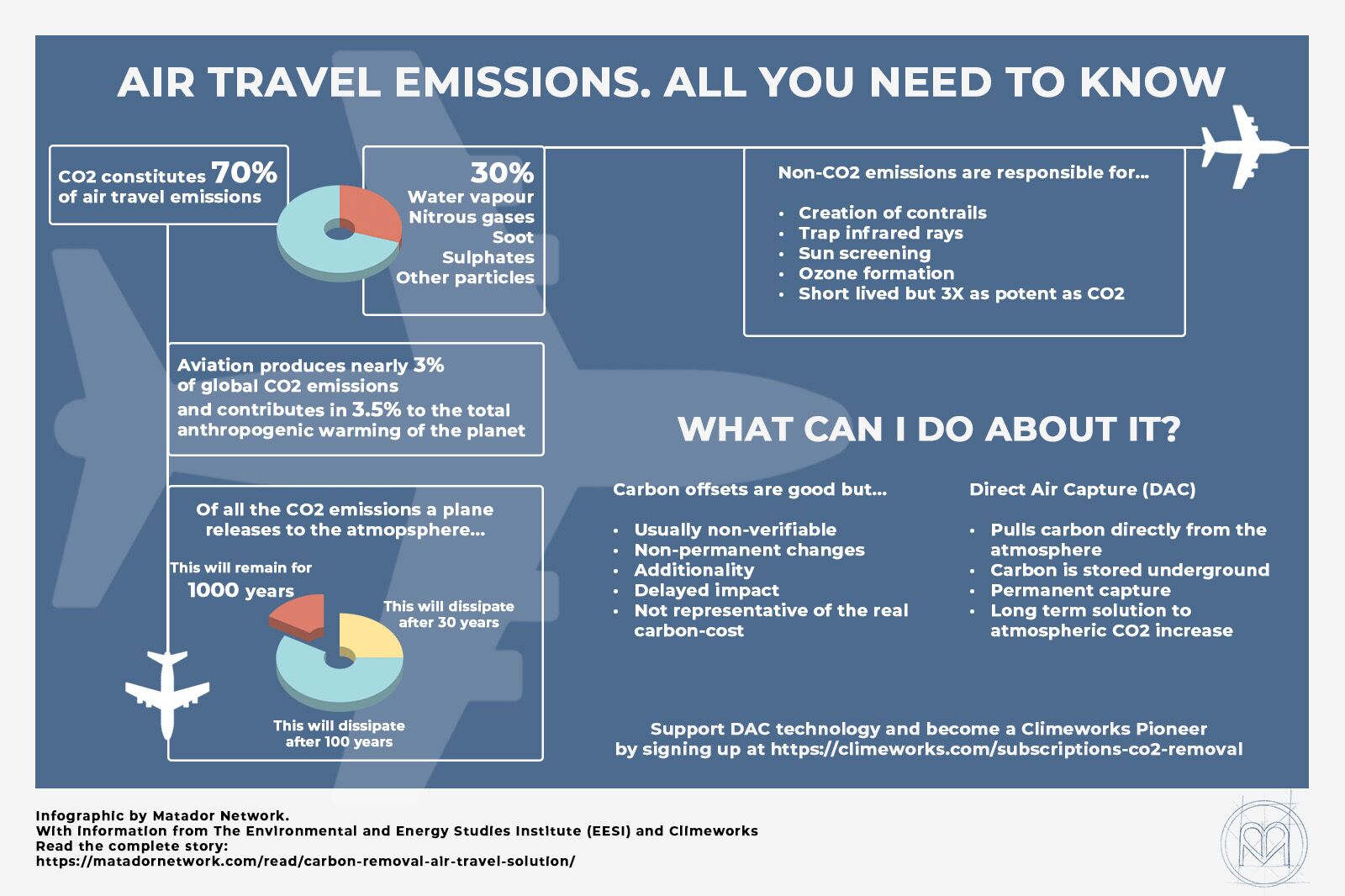

Infographic compiled and designed by Rulo Luna/ Matador Network

Dmytrenko argues that airlines must play a notable role in scaling this technology and incorporating it into their long-term sustainability efforts. She cites commitments from SWISS/Lufthansa Group and British Airways as examples of how this is currently being done, and notes that consumers must play a role as well.

“Progress happens by airlines starting to commit a fraction of their budgets to durable, verifiable carbon removal, helping this industry to scale and bring down costs,” Dmytrenko, from Climeworks, says. “Due to the thin margins of airlines, it may be that airlines’ customers may play a bigger and even more mandatory role in removals. Today through voluntary purchases, tomorrow because there will be policies in place requiring airlines to neutralize emissions with carbon dioxide removal.”

The travel industry, and airlines in particular, have heavily relied on carbon offsets to at least give the appearance of effectively countering a flyer’s emissions. But pulling carbon straight from the air and storing it underground as rock is emerging as a way for the travel industry – and society at large – to correct some of our past climate-harming sins. As a traveler, you have a role to play in bringing this technology forward.

When carbon offsets aren’t enough

Photo: True Pixel Art/Shutterstock

Air travel is a significant contributor to global carbon emissions, accounting for approximately 2 to 3 percent of total global CO₂ emissions. This may seem modest, given that it’s far behind the damage done by industrial agriculture (about 10 percent) or the behemoth that is energy production (about 70 percent). However, the impact of aviation is amplified due to the high-altitude release of greenhouse gases, which leads to a more potent warming effect. Airplanes burn fossil fuels, primarily jet fuel, producing CO₂, water vapor, nitrogen oxides, and other pollutants.

It’s true that flying has become more energy efficient through better design and engineering — more than twice as efficient per passenger since 1990. But that has not kept up with the growing demand for air travel, which quadrupled between 1990 and 2019. Aviation emitted about half a billion tons of CO₂ in 1990, compared to about 1 billion in 2019.

The type of travel you do plays notably into your carbon footprint. Long-haul flights typically produce more emissions per trip, but it’s the short flights that drive up per-passenger-mile emissions due to less efficient fuel use during takeoff and landing. Add in a layover or two – therefor extra takeoffs and landings – and your carbon footprint gets bigger. As air travel continues to grow around the globe, the industry’s contribution to climate change is becoming increasingly significant, prompting calls for greener technologies, alternative fuels, and more efficient flight practices to mitigate its environmental impact.

“But Matador,” you say. “Can’t I just buy carbon offsets? My favorite airline even prompts me to buy them!”

You can, and if you do, that’s great. Offsets are certainly a step in the right direction. The primary issue with carbon offsets, however, is that it’s difficult to verify the actual impact of the money. At the most basic, carbon offset money is used to plant a tree – but was that tree actually planted, and more importantly, would it have been planted anyway? This breaks down a few ways. A primary concern is the issue of additionality — many offset projects, such as reforestation or renewable energy initiatives, would have occurred even without offset funding, meaning they do not truly offset your flight emissions, according to data from Earth Day..

Additionally, some projects, like forest-based carbon sequestration, suffer from impermanence risks. Forests can be destroyed by logging, wildfires, or natural disasters, releasing stored carbon back into the atmosphere and nullifying the intended benefits. For example, in 2024, a fire in a Brazilian Amazon wilderness area burned an area larger than Italy, releasing the carbon stored in that area of forest and nullifying the benefits of preserving that area, according to reporting from The Guardian.

Offset programs also frequently lack verification and transparency, raising concerns about whether the promised carbon reductions are actually achieved. The Guardian, again, found that more than 90 percent of rainforest-based carbon offsets are “useless,” offering no actual benefit to the planet. Many projects provide a delayed impact, particularly tree planting, which can take decades to sequester the amount of carbon equivalent to the emissions from a single flight.

While offsets can play a role in broader climate strategies, they should not be relied upon as the primary solution. Reducing emissions at the source — through advancements in aircraft efficiency, sustainable aviation fuels, and by wider adoption of lower-carbon travel alternatives like electric trains and buses — is essential to addressing the environmental impact of flying, and of travel more broadly.

Ok, but the world isn’t going to stop traveling. So what’s the solution?

Photo: Climeworks

Before going further, it’s important to note that the overwhelming amount of carbon emissions put out into the world every day are not any one person’s fault or responsibility. While society asked for, and worked toward, technological advancements that allow us to easily travel, people didn’t ask for it to be done in a manner that destroys the planet in real time. Let alone that happening while the oil and gas companies fueling the change sit back and profit immensely while doing little-to-nothing to counter their impact (and in some cases, lobbying against or working to prevent cleaner methods of travel from gaining a foothold). Oil companies, and their trade associations including the Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA), for example, have spent millions lobbying against California’s EV mandates and the state’s proposed bans on new gasoline-powered vehicle sales by 2035.

To better grasp the marketing campaign to place the blame for carbon emissions on individuals, I highly recommend reading Auden Schendler, the “sustainability guy” at Aspen One, Schendler elaborates at length on this topic in his two books while proposing vast societal solutions. In an earlier conversation I had with Schendler, he discussed how BP invented the concept of the “personal carbon footprint” as a means to shift blame from the company to the individual, and why it doesn’t inherently make someone a hypocrite for both caring about the environment and driving a car to work in the morning. The decision that this is how life would require people in society to operate was made long before the car was sold to the buyer.

Still, people need solutions. Scaling sustainable aviation fuel to the quantities needed for commercial aviation is still decades away, if it’s possible at all. For one, it’s more expensive to produce, and likely will require ample land for production of corn ethanol or other sources for the fuel. In 2023, the average price of conventional jet fuel was about $3.86 per gallon, compared with $6.69 per gallon for sustainable aviation fuel. Hurdles also exist for electric aircraft, from safety to range. Early signs from the Trump administration since taking office on January 20, 2025 suggest that federal support for sustainable aviation fuel and carbon removal will be negligent during Trump’s second term, leaving the onus on airlines and their customers.

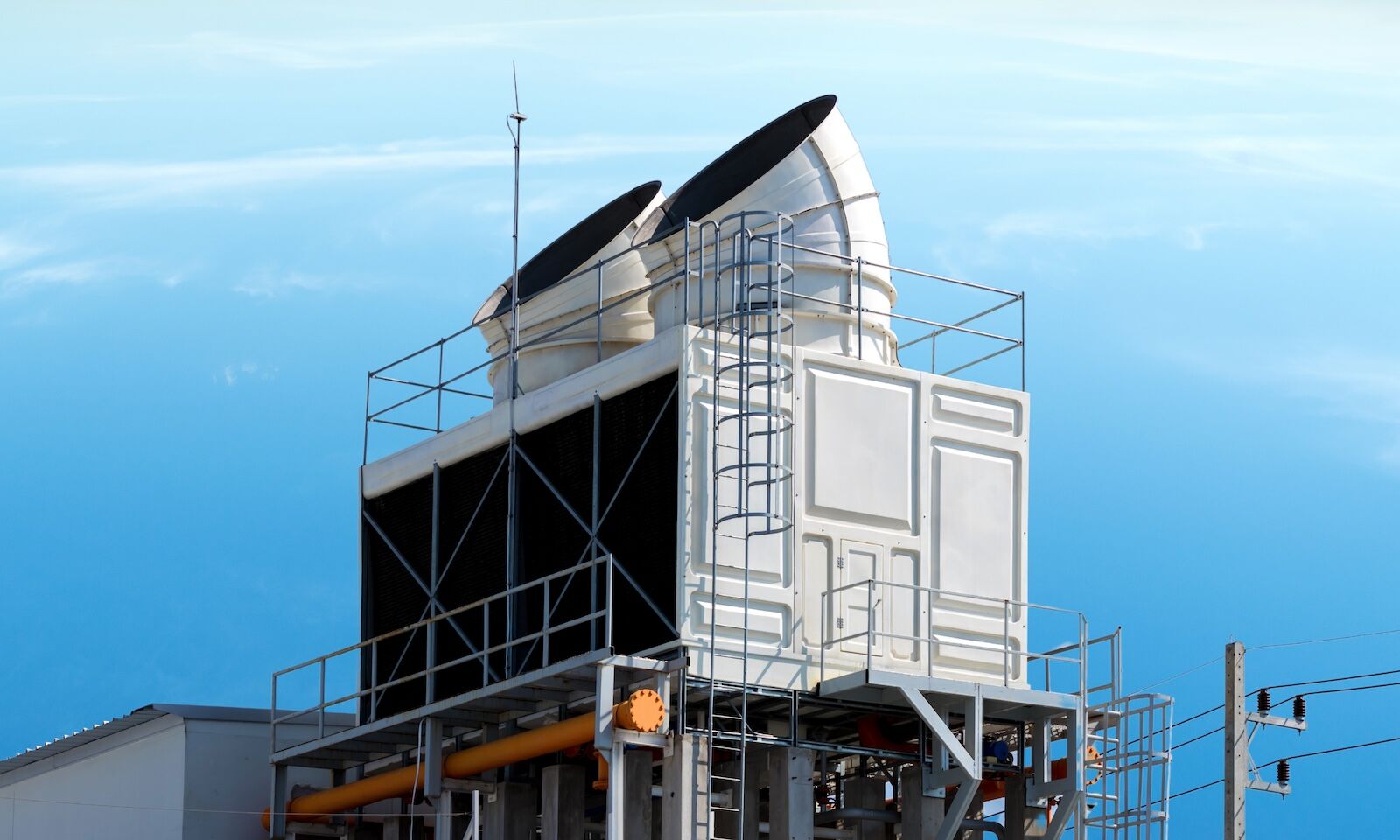

Carbon removal, and to a lesser degree carbon capture, are stopgaps that are increasingly accepted both in scientific circles and in mainstream climate rhetoric. At the core, these processes are similar: both seek to remove carbon from the atmosphere and turn it into stone as storage, typically underground. Carbon capture does so at its source — by placing capture devices at the emissions points of a coal-powered power plant or an industrial smoke stack, for instance.

Carbon removal, or direct air capture (DAC), focuses on pulling carbon from the atmosphere. This can be done naturally, through processes like re-forestation and coastal or wetland restoration. And it can be done through man-made technology. While offset programs can plant trees or work to rehabilitate wild spaces, DAC is measurable, quantifiable, and verifiable. The machines used to pull carbon out of the air and convert it to rock to store underground operate on various sets of data points and their effectiveness (how much carbon they’re sequestering) can be reliably measured.

Tomorrow’s Air is the leading voice for carbon removal in the travel industry. The organization, founded by Nim de Swardt and Christina Beckman (also known for her work with the Adventure Travel Trade Association), exists to “educate, inspire, and mobilize a global collective to reduce, remove, and permanently store carbon dioxide emissions,” as its website states. De Swardt and Beckman first had the idea for Tomorrow’s Air while on an expedition to Antarctica, where they first learned of carbon capture and felt the adventure travel industry needed to embrace it as a way to offset its footprint.

“Tomorrow’s Air is trying to rally consumers to the cause because we have seen consumer movements launch major change for environment or workers rights in the past,” Beckman tells me. “Consumers participating in carbon removal programs sends a powerful signal that they understand, that they care, that they’re willing to pitch in. This signal enables policy makers and investors to engage more fully.”

Beckman encourages travelers to get involved and follow the progress through the group’s Instagram, LinkedIn, and newsletter. The group takes monetary payments that are directed toward either carbon removal or sustainable aviation fuel, whichever the funder prefers.

Implementing carbon removal technology

The Orca Direct Air Capture plant in Iceland. Photo: Climeworks

Climeworks is the most recognized company implementing carbon removal. In addition to Orca, the company is developing Mammoth, a larger facility in Iceland expected to capture significantly more CO₂ annually.

In March 2024, SWISS, a subsidiary of the Lufthansa Group, became the first Climeworks airline customer when the company signed a long-term carbon removal agreement. This partnership is designed to scale DAC technology to help combat global warming and advance sustainable aviation practices. The commitment marked the first airline industry step in supporting DAC technology in sustainability strategies.

British Airways has also partnered with Climeworks to help fund its growth by incorporating DAC into its efforts to reduce emissions. In September 2024, the airline partnered with Climeworks to remove a portion of its carbon emissions and, like SWISS, help stimulate the growth of the carbon removal market. British Airways has further supported DAC development by purchasing carbon removal credits from Climeworks facilities in Iceland and another project, 1PointFive’s upcoming DAC plant in Texas.

“Progress happens by airlines starting to commit a fraction of their budgets to durable, verifiable carbon removal, helping this industry to scale and bring down costs,” Dmytrenko, the Climeworks spokesperson, says. “Due to the thin margins of airlines, it may be that airlines’ customers may play a bigger and even more mandatory role in removals. Today through voluntary purchases, tomorrow because there will be policies in place requiring airlines to neutralize emissions with CDR.”

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change estimates that five-to-10 gigatons of CO₂ need to be removed by 2050 to keep the world from passing the climate tipping point of temperatures rising by 1.5 degrees celsius. The United States would need to remove about one gigaton per year by 2050 to reach that goal when accounting for the increased emissions from industry growth.

“Which is why there is a sense of urgency now,” Dmytrenko says. “The industry is nowhere near a megaton of removals today. Today, and the next decade, have to be focused on scale up to be where we need to by 2050. If you wait until 2050, you’re too late. If we wait until 2040 to get started, we’re too late. As in any industry, the technology is developed, improved, and iterated as we go. We need time for that ramp up.”

The argument against carbon removal to offset travel emissions

Carbon capture devices atop an industrial facility capture carbon before it’s released into the atmosphere. Photo: Keshi Studio /Shutterstock

One primary argument against carbon removal is that it simply allows polluters to continue polluting with the promise of cleaning it up later.

“Using Direct Air Capture (DAC) for carbon removal — whether for aviation emissions, cement, or to offset other fossil fuel emissions — is a bad idea,” Jonathan Foley, the executive director of Project Drawdown, told me via email.

Project Drawdown is a non-profit organization that aims to help the world reach “drawdown” — the point in the future when levels of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere stop climbing and start to steadily decline. “First of all, DAC doesn’t actually work as a climate solution. It uses a gigantic amount of energy to remove carbon from the free atmosphere, and that energy has a cost. If the DAC plant is powered by fossil fuels, clearly there’s a problem. But even if the DAC plant is powered by renewables or geothermal energy, there’s still a huge opportunity cost — where zero-carbon energy would have been far better used on the grid, displacing fossil fuel emissions. Until we eliminate fossil fuel emissions from energy altogether, using energy-intensive DAC is a net source of extra emissions, full stop.”

This point is valid to a degree, but with a big caveat: There isn’t going to be a day when we can simply “flip the switch” on carbon emissions and stop emitting, end of story. As it stands, vast sectors of the global economy depend on burning fossil fuels in order to function. Even if you believe — as I and many climate experts do — that a global transition to renewable energy is inevitable and underway, these various sectors won’t hit a “clean” threshold all at once. Some, like aviation, likely never will be completely “clean.”

Foley argues that scaling DAC to the point where it can make a notable impact is both too expensive and misses the point of fighting climate change altogether.

“We’d be far better off finding ways to cut the direct emissions from aviation by flying a little less, making flights more efficient, reducing contrail production in flights (an easy fix), and (down the road) producing low-carbon aviation fuel,” he says. “While ‘sustainable aviation fuel’ is in the very early stages and nowhere near a complete solution, it is thermodynamically much more promising than pursuing DAC as a solution to these carbon emissions. Trying to justify DAC as a ‘solution’ to aviation emissions might be attractive for tech billionaires who want to fly private jets and can afford their own DAC purchase agreements, but it’s not a real solution to the bigger problem.”

On a broad scale, though, global air travel is set to increase 3 to 4 percent per year until at least 2040, due to factors including increased global wealth and population, according to data from the International Air Transport Association. From that angle, the argument is made by trade group Airlines for America and others that DAC should be part of the solution, even if not the entire pie.

The International Air Transport Association sent the following statement to Matador:

“Direct Air Capture and other forms of carbon removal are part of the technology suite that airlines are investing in now for potential deployment over the long term. Whether the captured carbon is sequestered or transformed into Sustainable Aviation Fuel (SAF), it has the potential to be a significant contributor to achieving the carbon reduction goals of the aviation industry.”

DAC’s cost is significant, and it’s more expensive to enact than sustainable aviation fuel. DAC’s cost largely stems from a lack of existing infrastructure and the energy needed to run the plants. The International Energy Institute notes on its website that DAC is the “most expensive application of carbon capture.” This is because atmospheric CO₂ is more diluted than the emissions coming out of gas plants, power stations, or cement plants. In short, DAC requires a high energy cost to execute and a high cost to implement.

Then there are the costs to businesses and travelers. A study published in the journal Nature found that flight prices would likely increase between 40 and 75 percent to incorporate DAC in a way that makes air travel carbon neutral by 2050, depending on how much the industry relies on DAC versus sustainable aviation fuel. In all likelihood, the industry will heavily rely on both, and costs will inevitably go up.

“This has always been one of the arguments against investment in new solutions,” says Beckman, of Tomorrow’s Air. “People will say, ‘just invest in trees, if we put all our money in trees, we wouldn’t need this stuff.’ This is simply not true. Society has waited too long, we have trillions of tons of CO₂ stored in our atmosphere at this point. Even if we stop burning fossil fuels today, tons of historical CO₂ emissions sitting in the atmosphere will continue to warm the planet, causing dangerous climate conditions for at least another 1,000 years.”

To avert the worst of climate catastrophes, we need solutions from every angle. This includes pulling carbon from the air to offset historical emissions as well as the future emissions of industries that aren’t clean yet, and may never be.

Putting Direct Air Capture into practice

Climeworks engineers work on models at the Orca plant in Iceland. Photo: Climeworks

Dmytrenko notes that travelers can help by encouraging their lawmakers to rally behind DAC initiatives. Travelers can also sign up to be a Climeworks Pioneer, which involves a monthly donation that goes toward scaling the technology and eventually offsetting their personal carbon footprint.

Going forward, humanity’s love of travel and exploration won’t dissipate. It appears quite the opposite, actually, as Skift reported that international travel numbers returned to pre-Covid levels in 2024. Hopefully, innovative solutions like DAC continue to scale to keep our vagabonding as sustainable as possible for the long-term.

“In the future, this will be an all-hands-on-deck exercise: governments, the aviation industry (through e.g. public-private partnerships) and consumers sharing the cost of removing the unavoidable carbon dioxide emissions that are put into the atmosphere by air travel,” Dmytrenko says. ![]()

![From Gas Station to Google with Self-Taught Cloud Engineer Rishab Kumar [Podcast #158]](https://cdn.hashnode.com/res/hashnode/image/upload/v1738339892695/6b303b0a-c99c-4074-b4bd-104f98252c0c.png?#)